Fighting for Health: The School in Wartime

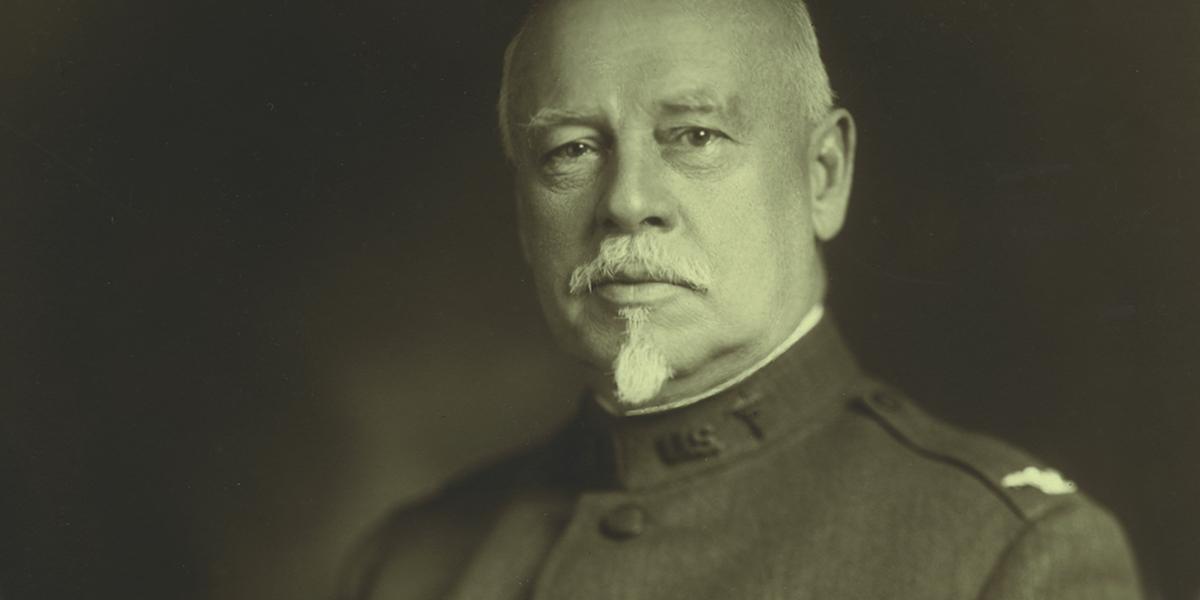

The letter arrived shortly after August 29th, 1918, with a stark subject line: "Orders." Sent by the Adjutant General of the U.S. Army, it was addressed to William Henry Welch informing him that he would proceed to several military camps along the southeastern United States "for duty in connection with the investigations of pneumonia."

The 68-year-old Welch no doubt wondered how much longer the Great War, already in its fourth year, would last. One thing was certain: the Central powers were not the only enemy. The men of the U.S. military faced the threats of tuberculosis, influenza, pneumonia, and venereal disease. This battle against disease was one the Americans appeared to be losing.

So the nation turned for help to Welch, former president of the National Academy of Sciences and founding dean of the country's first school of public health. It was not the first time during World War I that Welch, MD, DSc, LLD, found his expertise in demand. Nor would it be the last time that the School would find itself engaged in a national wartime emergency. Throughout the major conflicts of the past century — World Wars I and II, the Korean War, Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the ongoing war against terrorism — faculty from the School have played pivotal roles in the fight to slow illness and contain the spread of disease.

The pursuit of public health in the face of battle is not without bitter irony: public health professionals have a mission to save the very lives that war seeks to destroy. Reconciling these two opposing objectives has not always been easy for the School's public health practitioners. And the struggle has only intensified in recent decades, as the face of war has changed dramatically. The trench warfare of World War I has yielded to wars with less defined battlefronts, displacing civilian populations and creating mass movements of refugees dogged by illness and disease. And as Sept. 11 and the fall's anthrax attacks have shown, civilian populations themselves have become targets in warfare's latest incarnation.

"War is the prototype of public health destruction," according to Frederick Burkle, MD, MPH, senior scholar at the School's Center for International Emergency, Disaster and Refugee Studies. It's an apt explanation: Whatever its form, war is the ultimate threat to public health. Yet when the nation has called the School to war, its faculty and alumni have resolutely done their part, seeing the enemy not in the faces of combatants but in the bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens that threaten public health.

World Wars I and II, and Korea

In some ways, the School itself almost became a victim of World War I. The Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health was expected to open in October 1917, but Welch, its driving force, had joined the war effort in July — three months after the United States entered the war. He temporarily abandoned the project in order to accept an appointment as a major in the Officer's Reserve Corps. (The School opened a year later, in October 1918.)

Welch traveled along the East Coast, inspecting military facilities, training camps, and army barracks to report on soldiers' health in the camps and to make recommendations for improvements to the War Department. With an army of only 200,000 men when the country entered the war, the United States hastily constructed 32 training camps across the country, giving little thought to potential public health hazards.

With thousands of young American men away from home for the first time, the dire threat of venereal disease emerged. Effective treatments would not be available until Alexander Fleming's discovery of penicillin in 1928, and many feared that returning soldiers, reluctant to disclose their symptoms (including chancres, rashes, fevers, and sore throats), would infect their wives.

In addition, the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918 also posed an acute threat to American troops and civilians; in March of that year, soldiers in a Kansas military camp complained of high fevers and sore throats. Within one day, 100 soldiers were ill, a number that shot up to 500 by the week's end. The epidemic spread to other camps and to civilian populations, killing 675,000 Americans — five times the number that would die in the war.

Pneumonia, tuberculosis, malaria, and other diseases also proved to be mighty challenges. Welch arrived at the camps with a mission to help the men survive their training. On December 26, 1917, he carefully surveyed ill servicemen at Camp Travis, Texas, and recorded 380 cases of measles, 124 cases of the mumps, 178 cases of pneumonia, and 14 cases of meningitis among the camp's 34,000 inhabitants. Welch scribbled in his journal that the facilities have a "great deal of dust — then pneumonococcus. Have had much conjunctivitis, and sore throat-colds." He also noted that "sanitation is neglected and camp disorganized" and concluded forebodingly, "Fear outbreak." Welch recommended that the hospital be sent additional nurses, more medical officers with public health training, sterilization supplies, and Rockefeller type I pneumonia serum.

While the nascent School spent the Great War getting on its feet, it acted definitively after the war's end. Public health was still a new field in the United States, and one of the great lessons from the recent war was the need for medical officers trained in controlling epidemics. In May of 1923, the School granted a Surgeon General request that U.S. Army medical officers who had taken courses in preventive medicine and had experience as sanitary inspectors be admitted to the School for a DrPH degree.

In less than 20 years, the public health field — and the mettle of the School itself — would be tested as the United States entered World War II. So many of the School's students and faculty joined the war effort that the School's then-Dean Lowell J. Reed, PhD, proclaimed in a wartime newsletter: "Some of you have probably wondered whether we would continue to have any students at all during the war — we did ourselves."

In spring 1942, the School received a special request from the National Research Council to develop and offer public health training courses that, according to the minutes of the School's Health Advisory Board, would educate "personnel to meet the increased demand in the field of public health caused by the present emergency." Faculty devised three courses: Venereal Disease Control, Clinical Laboratory Methods, and later Epidemiology. Army and Navy medical officers were pulled from active duty for up to four months at a time to enroll in the unique 6- to 12-week courses.

The Army had originally rejected men with any form of venereal disease (VD), but increasing war casualties and the need to replenish forces changed that policy. By 1943, 12,000 American men with VD were being inducted into the Army every month. Despite penicillin's availability, VD continued to pose a vexing problem, and several faculty members were called upon to help control outbreaks among the troops. While consulting for the Surgeon General, Margaret Merrell, ScD '30, professor of Biostatistics, designed studies that evaluated penicillin's success in treating syphilis. J. Earle Moore, MD, professor of Public Health Administration, developed programs to contain syphilis outbreaks in the military camps and later chaired a venereal disease control subcommittee for the National Research Council, which advised the armed forces.

The School also launched the Army Industrial Hygiene Laboratory in October 1942, housing it on the seventh and eighth floors of the Wolfe Street building. Seeking women to fill factory jobs left vacant by men heading off to war, the government had promoted the image of "Rosie the Riveter." But what effect did such work have on the health of women? Anna Baetjer, ScD '24, professor of Physiological Hygiene, concluded that certain measures, such as adjustments to machinery and more flexible schedules, should be implemented to accommodate women's different needs. Baetjer's study was published in 1946 as Women in Industry, Their Health and Efficiency, long considered a classic in the field.

Overseas, the humid climates of Asia and the South Pacific provided a fertile breeding ground for malaria-carrying mosquitoes, and the disease quickly became a major threat to American servicemen. During the war, the School provided critical support to Hopkins' Office for the Survey of Antimalarial Drugs, an effort that would evaluate more than 13,000 drugs for their efficacy in malaria treatment. An entire floor at the School was used to house ducklings on which candidate drugs were tested. The survey identified chloroquine as the preeminent antimalarial. Overseas, former faculty member Justin Andrews, ScD '26, Medical Zoology, the first scientist to attain the rank of general, led an Army malaria control unit. Under his direction, the Army drained mosquito breeding areas and used diesel oil and DDT as insecticides and larvicides. Such efforts proved effective: Just 0.1 per 1,000 Americans quartered in the United States were infected with malaria in 1945, as compared to 7.5 per 1,000 in 1917 during World War I.

In the Philippines, Johns Hanks, PhD, professor of Pathobiology, was living with his family and researching leprosy when the war began. Once the Japanese had occupied the islands, Hanks found it almost impossible to acquire the supplies he needed to continue his research. Putting his creativity to the test, he began producing his own supplies by using plant components and spring water. He and his wife, Julia, briefly became prisoners of war during the Japanese occupation.

There were others who found themselves too close to the action for comfort. Alan W. Donaldson, ScD, a professor of Parasitology, who served as captain of the Sanitary Corps' 28th Malaria Unit in the Pacific from 1943 to 1946, wrote from the Philippines: "This is the third time we've been moved in with the combat troops. Thus far, we've been lucky in that no one in our unit has been hurt as the result of enemy action, but these have been times I would have given a lot to be some place else."

During the Korean War, the School conducted training programs with the U.S. Air Force. Ernest Stebbins, MD, MPH '32, then Dean of the School, was especially involved in this collaboration, participating in studies of public health administration, while Paul Lemkau, MD, professor of Mental Hygiene, developed courses in military mental health for the Air Force. The School continued to pursue VD research while the war raged in Korea. The 1952-1953 academic year marked the School's largest post-war group of special students studying VD prevention and control.

The Changing Face of War

In the second half of the 20th century, the changing face of war has meant that battles are fought more frequently in and near villages and cities, and less often in trenches and on battlefields. The School's faculty members who served in Vietnam, and more recently in Sudan, Iraq, Rwanda, and Bosnia, have found themselves dealing with civilians as much or more than soldiers.

Public health practitioners increasingly find themselves working on the health problems that arise from collapsed internal social structures, displaced citizens, and the obliteration of "normal life" for civilians. As war destroys homes and villages, many become refugees, stuck in temporary camps with poor sanitation that often leads to public health catastrophes, notes W. Courtland Robinson, PhD candidate and research associate at the School's Center for International Emergency, Disaster and Refugee Studies (CIEDRS).

Frederick Burkle, who was drafted into the Vietnam War in 1968, was stationed at a casualty receiving facility in Dong Ha, six miles from the demilitarized zone. Fighting occurred mostly at night, which was when the casualties came in. His daytime hours, however, were far from restful, as nearby families and refugees — who had no other medical care available in that province — flooded the center.

"We saw up to 250 children a day," he said. One morning he saw a suspicious abscess under a child's arm and his Laotian interpreter, trying to translate, took out a dictionary and pointed to the Vietnamese word for "plague." Burkle saw five similar cases that same day, and realized that he was facing a potential outbreak of bubonic plague, transmitted quickly by rats found in abundance in the refugee camps. Relying on a drug treatment of tetracycline and chloramphenicol, Burkle eventually treated a total of 155 children and scores of adults in what turned out to be the "worst epidemic" of plague that century in Vietnam, he recalls. That year, the number of plague cases in South Vietnam totaled 780, almost 60 percent of the reported cases worldwide.

Physical trauma is not the only problem afflicting displaced people. During the civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example, the School's Carl Taylor, MD, DrPH, professor emeritus,

International Health, struggled to establish early care and rehabilitation programs for children suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). "Psychological care is just as important as physical care during times of war," says Taylor.

Gilbert Burnham, MD, PhD, MSc, associate professor, International Health, who spent six years in the military and currently directs CIEDRS, notes that public health professionals are often the ones on the front lines. While political scientists can theorize about the social collapse that occurs during and after wartime, Burnham says, the mission of public health professionals is to "be there — to collect data and restore order."

Mike VanRooyen, MD, MPH, who also directs CIEDRS, knows how difficult it is to impose order in an environment of guns and killing. While he worked in a civilian hospital in southern Sudan, VanRooyen was uncomfortable that armed combatants often sought treatment there. "We decided on a policy that we'd treat soldiers only if they checked their weapons at the door," he explains, "and we enforced it. They were civilians when they entered, not soldiers."

Taylor also found himself on the front lines while on a mission for UNICEF in Baghdad, in the days just prior to the Gulf War. He and a colleague were whisked from their hotel by two armed men, who drove them to the compound of Yasser Arafat, then-chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Arafat treated the two doctors like emissaries from their country, explaining to them his political motivations in siding with Saddam Hussein. Two days later, Taylor left Baghdad on the last flight out of the city before American bombs began raining from its skies. (He would later return on a mission for Physicians for Human Rights to work on the alarming malnutrition and PTSD rates among Iraqi children, the results of war and sanctions.)

Despite the diametrically opposed objectives of war and public health, VanRooyen believes that "medical diplomacy" can be a positive, essential force in a crisis. "We can make real collaborative efforts," he adds, "because public health has an important role to play."