Smoke Out!

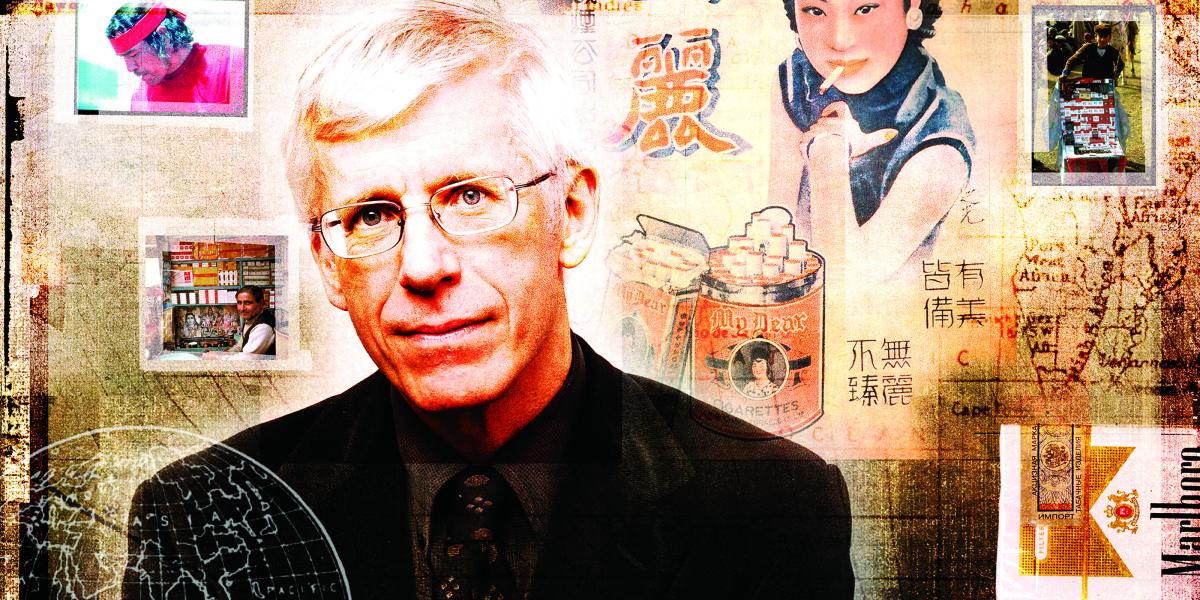

Jonathan Samet and the Institute for Global Tobacco Control are using science and education to extinguish a tobacco epidemic that threatens 1.1 billion smokers around the world—and everyone else.

In rural India, people still believe in the magic of tobacco. Villagers think tobacco can rid them of toothaches, sweeten bad breath, or soothe their bowels. In Tirana, Albania, “Marlboro girls” in short skirts stroll the streets handing out free packs of cigarettes. In Japan, the government must by law promote development of its tobacco industry. In Lima, Moscow, Kampala, and Kansas City, advertising links cigarette smoking with vitality, sexiness, slimness, and even health.

Myths, misconceptions, and lies about tobacco abound in a world where 1.1 billion people smoke. Global debates over public smoking, advertising bans, and tobacco taxes are clouded by industry influence, politics, and cultural beliefs. Yet the science on the health effects of tobacco has never been more clear.

Smoking kills.

And in the coming decades, smoking is going to kill in numbers that beggar the imagination. By 2030, health experts estimate that deaths from tobacco will surpass any other cause—more than from AIDS, tuberculosis, car accidents, homicide, suicide, and childbirth combined . Ten million people per year are projected to die from tobacco by then, accounting for one in six deaths worldwide. And if current trends continue, 500 million human beings—half a billion people—now alive will die from tobacco.

The global tragedy spawned by tobacco is only made worse by the epidemic’s evolving nature. The wave of tobacco consumption that surged in the 20th century through the world’s prosperous nations is now breaking where it can least be afforded: in developing countries. By 2030, an estimated 70 percent of smoking-related deaths will occur in the developing world. Beyond the staggering toll on human life, the health care costs and the years of lost productivity will drain already fragile economies.

In China alone, there are 300 million male smokers—a number greater than the entire U.S. population. One hundred million Chinese men alive today will die because of tobacco, according to World Bank estimates.

To Jonathan Samet, MD, MS, an international authority on tobacco’s effects on health, the question is stark: What should the world’s number one school of public health do about the world’s number one preventable cause of disease?

In the mid-1990s, Samet saw that the best way to quickly make a global impact in tobacco control was to work with colleagues abroad. U.S. researchers like Samet had already been tracking the tobacco epidemic for decades and could help international colleagues adapt U.S. research expertise to their own situations. “We need to make certain the knowledge we have is translated to the developing countries—how tobacco companies work, how to count the bodies so we can say what is going on,” says Samet, Epidemiology chair and the Jacob I. and Irene Fabrikant Professor in Health, Risk, and Society (see sidebar). Knowing the scale of a country’s tobacco epidemic, as well as the machinations of tobacco companies there, can give researchers the evidence needed to convince governments to adopt new policies and intervention programs.

To realize this vision, the School founded the Johns Hopkins Institute for Global Tobacco Control (IGTC) in May 1998. Initial funding came from Glaxo-SmithKline (then SmithKline Beecham), a maker of smoking cessation products. “It was really this common alignment… of people who had a mission to reduce the ill effects of smoking,” says Catherine Sohn, PharmD, a vice president at GlaxoSmithKline.

Just as globalization pried open national markets and flooded economies with cheap goods like TVs and computers, it’s also helped multinational tobacco companies like Philip Morris. “It’s the same players in every country,” says Samet. “They’ve bought up the old national tobacco monopolies. Part of the problem is they take a sleepy national monopoly and remake it into an aggressive multinational.”

Ministries of health and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) realized that they must share data, policy ideas, and programs to form a concerted defense against the multinationals. With its emphasis on international cooperation, IGTC was in a perfect position to help.

“We have to work with people in developing countries to better understand how to translate our successes,” says Frances Stillman, EdD, the Institute’s co-director. “It’s not just providing them with the funding but working alongside them to get their programs up and running.”

In its first five years, the Institute has launched studies and programs around the world, including:

- Studies in Poland, China, India, Mexico, and Brazil that measure levels of cotinine (a breakdown product of nicotine) in smokers to determine the relationship between what people smoke, how they smoke, and how much nicotine enters their body. Results will be reported in August.

- The Fogarty International Project in China and Latin America. Sponsored by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), this project is developing smoking research and surveillance capabilities.

- A study of levels of secondhand smoke in Latin America. A common protocol measures people’s exposure to passive smoke in public places (see sidebar).

- A global network to link tobacco control researchers (funded by the National Cancer Institute).

- A 2000 conference on tobacco control in Beijing that helped set tobacco control policy recommendations in China.

For thousands of years, since American Indians began smoking Nicotiana tabacum, and especially since 16th century explorers brought the plant back to Europe, cultures around the world have taken to tobacco with different degrees of ritual, affection, and addiction

"I think every place is special because of the nature of the tobacco industry and what it does,” says Samet. “How people smoke and what smoking means; what the policy apparatus is like. Is there a tobacco control office? Are there regulations? Is the tobacco industry very powerful or not so powerful? And so on.

“Of course, there is some comparability everywhere,” says Samet, “because everywhere nicotine is addicting.”

The following snapshots from the United States, Mexico, Poland, India, China, and Japan comprise a kind of global tobacco tour, examining the evolving tobacco epidemic in each country and the research IGTC experts and local colleagues are conducting there.

United States

Tobacco’s story in the United States has three parts: historic leaps in scientific knowledge about tobacco’s health effects, a burgeoning tobacco control movement, and a continuing multibillion dollar cigarette business. Over the decades, science has built an irrefutable case against tobacco (one milestone dates to the mid-1930s when the School’s first Biostatistics chair, Raymond Pearl , found that nonsmokers live longer than smokers). But the American tobacco industry gave ground grudgingly. It spent billions on advertising and hired scientists to dispute studies that linked smoking to disease. Yet the percentage of U.S. men who smoked still fell from a high of 68 percent in 1955 to 26 percent in 2000. Smoking’s peak years were followed in later decades by the now-predictable epidemics of lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, strokes, and other illnesses. Today, tobacco kills about 440,000 Americans every year and costs the economy more than $150 billion annually, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Rounds of legal battles from the 1990s, including the Minnesota tobacco trial, have shattered any remaining tobacco industry dreams of increasing the U.S. market.

Led by state and local efforts, U.S. tobacco control has taken off in recent years. In 1988, Johns Hopkins Hospital was one of the first U.S. hospitals to go smoke-free. IGTC co-director Stillman guided that project and published its evaluation in the Journal of the American Medical Association, setting the standard for smoke-free hospitals. California banned smoking in restaurants in 1995 and in bars in 1998. And last fall New York City increased the city’s tax on cigarettes from 8 cents a pack to $1.50 and banned smoking in bars and restaurants. In advocating the legislation to the New York City Council, Mayor Michael Bloomberg (for whom the School is named) said, “Any reputable scientist will tell you that tobacco kills more New Yorkers than any other cause—roughly 10,000 people in this city each year, including some 1,000 from… ‘secondhand smoke.’ ” City health officials expect the tax increase will prevent 100,000 children from picking up the habit, help 70,000 New Yorkers quit smoking, and save 50,000 lives.

"For our leading city to do this is quite something,” says Samet, who testified in support of the regulations for the city. “I think it was quite courageous of the Mayor to move on this issue.”

Yet as tobacco use continues to fall nationwide, the United States remains one of the world’s major exporters of tobacco. Philip Morris, the world’s largest multinational tobacco company, had revenue of more than $47 billion in 1999, according to The Tobacco Atlas published by the World Health Organization (WHO). However, the diminishing U.S. market made tobacco companies like British American Tobacco and Philip Morris (maker of the world’s most popular brand, Marlboro) look to the developing world to expand their markets in the 1990s. “It is, you know, a sad story,” says Samet.

In Eastern European countries like Poland and the former Soviet republics, the multinationals discovered large markets of already addicted smokers willing to try international brands. Meanwhile, the developing world offered even greater potential. One of the millions of tobacco industry documents liberated through the Minnesota trial put it this way: “Thinking about Chinese smoking statistics is like trying to think about the limits of space.”

But the greatest frontier for tobacco companies isn’t a country but a gender: women, especially in Asia. While 60 percent of Asian men smoke, only about 5 percent of women smoke. Even slight increases in smoking by Asian women would bring fantastic fiscal rewards for tobacco companies and simultaneously deal a terrific blow to the region’s health.

For tobacco transnationals, the future is clearly not in the United States but in developing countries sufficiently prosperous to meet people’s basic needs and to afford a new addiction.

Unlike its neighbor to the north, Mexico is still caught in a growing tobacco epidemic. In Mexico, 32 percent of men and 16 percent of women smoke, according to Mauricio Hernandez-Avila, PhD, of Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health in Cuernavaca. And rates are increasing among the younger generation. Young women are smoking almost as much as young men. Hernandez attributes the change in smoking habits to tobacco advertising and the North American Free Trade Agreement, which reduced the cost of American cigarettes in Mexico.

Hernandez believes incontrovertible science remains the best means to persuade the government and the public to adopt tobacco control measures. He is co-investigator in the IGTC’s Fogarty International Project, which will bring researchers from China and Latin America to the School for training and work on various research projects. In one IGTC project, Hernandez is working with Mexico’s government health insurance agency to determine how much money tobacco-related illnesses siphon from the government health care budget. Results from a pilot study in the state of Morelos indicated that 6 percent of the health insurance budget goes to tobacco-related illnesses. Taking into account the limited health care available in Morelos, Hernandez estimates the national figure will be even higher.

To preserve the nation’s resources for other threats to health, Mexico must prevent its youth from starting to smoke. “If you want to decrease the number [of smokers] you have to attack the problem at the entry, and the entry is 12 to 18 years old,” he says. “That’s the window where 90 percent of Mexicans get hooked on tobacco.”

Hernandez wants to persuade Mexican politicians to increase the cigarette tax, a proven means of lowering consumption. However, that will prove difficult because industry lobbyists routinely defend the status quo. To counter the industry arguments, Hernandez holds frequent training sessions for Mexican state government officials. “You’d be surprised how little information there is in Mexico on how tobacco companies trick everybody, how they directly advertise to specific targets of the population,” Hernandez says. “I just think people need to have all information at hand when making decisions. Right now they have only false statements of what tobacco is.”

Poland

Witold Zatonski admits he’s not a typical Pole. He’s never smoked.

In the late 1950s, he and his two brothers tried to persuade their mother to stop smoking after she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. “Unfortunately, she was not able to stop,” says Zatonski, who believes the habit cut 10 years from her life. The experience made him a committed nonsmoker in a country that at one time had the highest smoking rates in the world. (In the mid-1970s, almost 80 percent of Polish males smoked daily.) As a young physician in the 1960s, Zatonski recalls doctors’ meetings in which nearly everyone smoked.

Zatonski, MD, PhD, a professor of cancer epidemiology at the Maria Sklodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Centre in Warsaw, traces Poland’s affair with smoking to the 20th century wars that overran Europe. Smoking, like venereal disease, famine, and cholera, seems to follow war. In postwar Poland, cigarette smoking was viewed as a sophisticated Western behavior. The national habit became so ingrained that in the 1980s the communist government provided Polish workers with a daily stipend of free cigarettes—whether they smoked or not. “The number of people smoking increased by 1 million or more,” Zatonski says. “It was really so crazy. It was unbelievable.”

The soaring smoking rates later led to subsequent increases in lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. Lung cancer mortality in Poland was less than half that of the United Kingdom (U.K.) in the 1960s, but by the late 1970s it exceeded the U.K. rates, according to Zatonski. “I very quickly realized that the number one cancer problem was tobacco,” he says. “The only way to change cancer incidence and morbidity in Poland is to make some success in tobacco control.”

With the 1989 fall of Poland’s communist government, Zatonski and his colleagues had more freedom to pursue tobacco research. Data from that research, coupled with a powerful anti-smoking lobby, led Poland to pass a comprehensive tobacco control law in 1995 that banned smoking in hospitals, schools, and closed spaces in workplaces. It also outlawed vending machines that sold cigarettes and banned radio and TV ads for tobacco products.

In addition to his own research, Zatonski is collaborating with Samet and IGTC’s multicountry cotinine study that explores the relationship between smoking habits, cigarette content, and nicotine dose. Initial results show that the risk is similar in every population and is not connected with the quality or number of cigarettes, says Zatonski. “It is showing there is not a ‘healthier’ cigarette,” he says. “Polish or Indian or Mexican, they all are having the same unhealthy influence on your body.”

India

When Mira Aghi, PhD, was working on a tobacco intervention project in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, and Kerala, she asked old men why they smoked. We get bored if we’re not doing anything, they told her. Ah, she said, so if you’re working you don’t need to smoke. No, they countered, you have to smoke to get some rest.

"They can give you any reason," Aghi says. “You smoke when you’re sad to get rid of the sadness. To enjoy happiness, you have to smoke."

Many in India don’t know that tobacco is bad for them. With low literacy rates and a population of 1 billion people, India presents a special challenge for tobacco control. The WHO has estimated that 43 percent of Indian men and 3 percent of women smoke, but smoking rates vary greatly depending on the location within India. “Among adult men, it can vary from about 15 percent to 80 percent in different parts [of India],” says Prakash C. Gupta, ScD ’75, a senior research scientist at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. In addition, Indians partake of tobacco in a variety of forms beyond regular cigarettes—another complicating factor for tobacco control projects. Bidis (tiny cigars so cheap that a few cents will get you 40) are smoked throughout the country. While less than 100 billion cigarettes are produced annually in India, 700 billion bidis are made there each year, according to Gupta. Additionally, gutka, a flavored chewing tobacco, has become very popular in recent years. (Gutka’s popularity has led to an epidemic of oral cancers—80,000 new cases per year, according to one estimate.)

Gupta knows the challenges of calculating tobacco’s effects on health in India; he is under-taking a study of 150,000 people in Mumbai. In addition, he is the epidemiologist in charge of India’s portion of IGTC’s multi-country cotinine study. “We know that tar and nicotine levels in Indian cigarettes are high and the manner of smoking could be different,” says Gupta. “It will be illuminating to look at the results.”

While researchers like Gupta and Aghi recognize the severity of the country’s tobacco epidemic, Indian politicians—absorbed by other, more prominent health concerns like AIDS and malnutrition—are just now considering national tobacco control policies. “Tobacco control is not a paid job in India,” Aghi says flatly. “All of us who are in tobacco control are doing some other kind of research jobs. This is more like a passion.” (The U.S. NIH sponsored the tobacco intervention project she worked on in the 1980s.)

The NIH project had a dramatic impact on her and the rural villagers, says Aghi, who co-authored a chapter on smoking initiation in Women and the Tobacco Epidemic , published by IGTC and WHO. “There were things like a woman telling her 2-year-old daughter to light a little cigar for her and the girl would have to puff it to make sure it was well lit,” she recalls. “This is how the habit in the little girls is also there.” By explaining what happens to the body as tobacco is chewed or smoked, Aghi educated people about the dangers and encouraged them to quit. “The job was very difficult but we had great success there, a great reduction in precancerous lesions in the mouth,” she says.

China

In the global tobacco control community, there is China… and then the rest of the world. One of every three cigarettes smoked in the world is fired up in China. Still in the early throes of its tobacco epidemic—cigarette sales have increased steadily since 1981—China is just beginning to see the health consequences of cancer and cardiovascular disease. By 2025, 2 million Chinese will die each year from tobacco-related illnesses, according to one study. This in a country whose government is essentially the largest tobacco company in the world; the China National Tobacco Corporation is a state monopoly.

As a UNICEF representative to China in the mid-1980s, Carl Taylor, professor emeritus in International Health, saw ominous portents in the clouds of cigarette smoke at social gatherings and medical meetings in China. A friend of China’s minister of health at the time, Taylor tried to impress on him the seriousness of China’s rising tobacco epidemic. “I kept telling him that by all indications the greatest cause of death in China was smoking, and we ought to do something about it,” recalls Taylor, MD, DrPH, MPH.

Preliminary data convinced government officials that smoking was a health threat, but more data on the extent of smoking in China were needed. So Samet, Karen Becker, MPH ’95, and Taylor collaborated with the Chinese Academy of Preventive Medicine on one of the largest studies ever conducted of one country’s smoking rates: China’s 1996 National Smoking Prevalence Study. The survey of 128,766 Chinese found that 63 percent of men and 3.8 percent of women smoke. Only one-third of those interviewed knew that smoking can cause lung cancer. Samet continues to collaborate with the study’s director, Dr. Gonghuan Yang. And recently, the Institute embarked on another major study with the Chinese Academy of Preventive Medicine. IGTC (with Fogarty support) is studying the effects of secondhand smoke on women and children in Chinese homes.

In a way, Hong Kong, where tobacco consumption peaked in the 1980s, can serve as an important bellwether of what’s to come in China, according to Dr. T.H. Lam, chair and professor of the Department of Community Medicine at the University of Hong Kong. “Hong Kong is between the U.S. and China. Hong Kong is 20 years ahead of China and 20 years [behind] the U.S.,” says Lam. "This will be a forewarning of what is very likely to happen in China and the rest of the developing world.”

In a similar fashion, Hong Kong can help predict the success of tobacco control programs in mainland China, says Lam. “The tobacco industry sees Hong Kong as a very important place to fight a battle,” says Lam. “If they win here, they will definitely win on the mainland.” Key issues debated recently in Hong Kong have been cigarette smuggling from the mainland where taxes are much lower than Hong Kong, an increase in tobacco taxes, and a ban on smoking in all restaurants.

A frequent collaborator over the years with Samet and IGTC, Lam joined Samet and Stillman in Thailand to conduct a recent workshop training Southeast Asian colleagues on writing research proposals. He recently enlisted Samet’s advice on a proposed study certain to capture male smokers’ attention. Lam is seeking funds for a randomized, controlled trial of smoking cessation for men with erectile dysfunction, “because it is often said smoking can cause impotence.”

Japan

After centuries of use, tobacco has sunk deep roots in Japanese culture and the country’s economy. This fact partially explains why the country has the highest smoking rates in the industrialized world. But perhaps the greatest reason is the traditionally cozy relationship between the tobacco industry and the government.

Any proposals the Ministry of Health may have to reduce the 600,000 vending machines in Japan or ban tobacco advertising are blocked by a powerful adversary: the Ministry of Finance. The arrangement is formalized in Japan’s tobacco business law, which guides government regulation and promotion of the tobacco industry. The state tobacco monopoly in Japan was privatized in 1985; however, the government still retains two-thirds ownership of Japan Tobacco. “It’s almost like ‘sham privatization,’” says Yumiko Mochizuki-Kobayashi, MD, PhD, of Japan’s National Institute of Public Health.

Since becoming “independent,” Japan Tobacco has aggressively increased its business, buying RJ Reynolds’ international operations in 1999 for $7.8 billion. The Japanese government depends on the $19 billion in annual revenue it reels in from tobacco taxes and Japan Tobacco dividends.

But the close ties between the government and Japan Tobacco have come at a cost to the country’s health. For example, the tepid warning on Japanese cigarette packs: Smoking may be harmful to your health. Be cautious about smoking too much. “It’s not very sophisticated,” says Mochizuki-Kobayashi. “It misleads smokers or the public—as if there might be any threshold or limit to be safe.” Many smokers believe smoking “too much” means smoking more than two or three packs per day, she says.

And while most of the world considers the case closed on smoking’s danger to health, in Japan the controversy lives on. Researchers supported by Japan Tobacco don’t deny smoking causes cancer, but say research should continue. “Delay tactics,” she says.

To clarify the threat to Japanese health, Mochizuki-Kobayashi, Samet, and colleagues are working on a joint report on tobacco and health in Japan due out in November that will make evidence-based policy recommendations to the Japanese government and health organizations. “I think we can learn a lot from [Samet] and his colleagues,” says Mochizuki-Kobayashi. “We don’t have any Office of Smoking and Health. We don’t have any Center of Tobacco Control in Japan. I would like to learn what kind of system is needed to do this work and what kind of strategy should be made with limited resources.”

In a world wide enough to include Indian villagers who have never heard of tobacco’s dangers, government bureaucrats in Japan who protect an industry that threatens its people’s health, and tobacco multinationals that deploy billion-dollar ad campaigns to develop profitable new markets, it would seem an impossible quest to design uniform global guidelines to deal with tobacco.

Yet that is exactly what the WHO is doing this year. Initiated by WHO Director-General Gro Harlem Brundtland, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control entered a final round of negotiations in February. The final agreement is scheduled to go to the World Health Assembly for approval in May.

For four years, representatives from 150 nations have struggled over issues of international law, free trade, and public health. The Framework Convention marks the first time WHO has used its UN-mandated right to forge international treaties and conventions. It deals with advertising and promotion of tobacco, smoking in public places, and tobacco smuggling. (Smuggling, done to avoid taxes, is a significant problem; an estimated 300 to 400 billion cigarettes were smuggled globally in 1995.)

The question is whether the Convention representatives will agree on tough new standards or settle for a watered-down version. (U.S. representatives, for example, have fought a proposed ban on all tobacco advertising.) “Making it acceptable but not weak is what the whole process is about,” says Judith Mackay, MBChB, and co-author of The Tobacco Atlas. “I think this is the perpetual problem for UN conventions."

Regardless of the Convention’s final wording, its debate is already having an impact, according to Derek Yach, MBChB, MPH ’85, WHO executive director of noncommunicable diseases and mental health. Convention participants—who come from finance ministries, customs offices, and other agencies, in addition to health ministries—have been schooled in tobacco issues by Samet and other experts. The repeated seminars over the years have evolved into “the best university of global tobacco control,” says Yach. Government representatives have acquired a deeper understanding of the epidemiology of tobacco-related diseases, industry tactics and advertising, and other tobacco control issues.

Still, any tobacco control successes won by the Framework Convention or IGTC will not come soon enough for Samet, Mackay, and their colleagues concerned about the future. “Even if we keep prevalence as it is at the moment, even if we reduce it somewhat, simply because of projected world population [growth], we almost certainly will have a lot more smokers in the world in 30 years," says Mackay. “That of course means more disability and death from tobacco. It’s very hard to be optimistic, but I still tend to be robust.”

For Samet, the tobacco story is far from finished because, oddly enough, the science is still unfolding. He tells the story of chairing a WHO meeting in Lyons, France, last June. He and his colleagues had gathered to draft an International Agency for Research on Cancer monograph on smoking and cancer (a document roughly equivalent to a world Surgeon General’s report).

He was surprised by what he learned there. “Still in that meeting, we were finding new cancers caused by smoking: cancer of the cervix, the stomach, cancer of the kidney, acute leukemia …" he says. “It’s quite remarkable, so many years on. We don’t know the whole story of how bad tobacco is yet.”