A Revolutionary in China

As a young man, John Black Grant, MPH ’21, thought about following in his father’s footsteps. The turn of the 20th century found James Skiffington Grant on a Baptist-financed mission to China, where he practiced medicine with an uncommon devotion to duty. When hospital beds were scarce, he’d take patients into his own home; once, he even gave up his own bed.

But the elder Grant wasn’t entirely sold on the big-picture value of his work. Treating patients in a poor and undeveloped country, he once told his son, is a little like “mopping the floor under an overflowing sink.”

The father’s experience must have had an impact. For while J.B. Grant earned an MD and spent years working in China, his focus would go beyond the individual to entire communities. The experimental programs he launched revolutionized public health practice while improving the lives of millions of people and framing terms of debate and investigation still going on today.

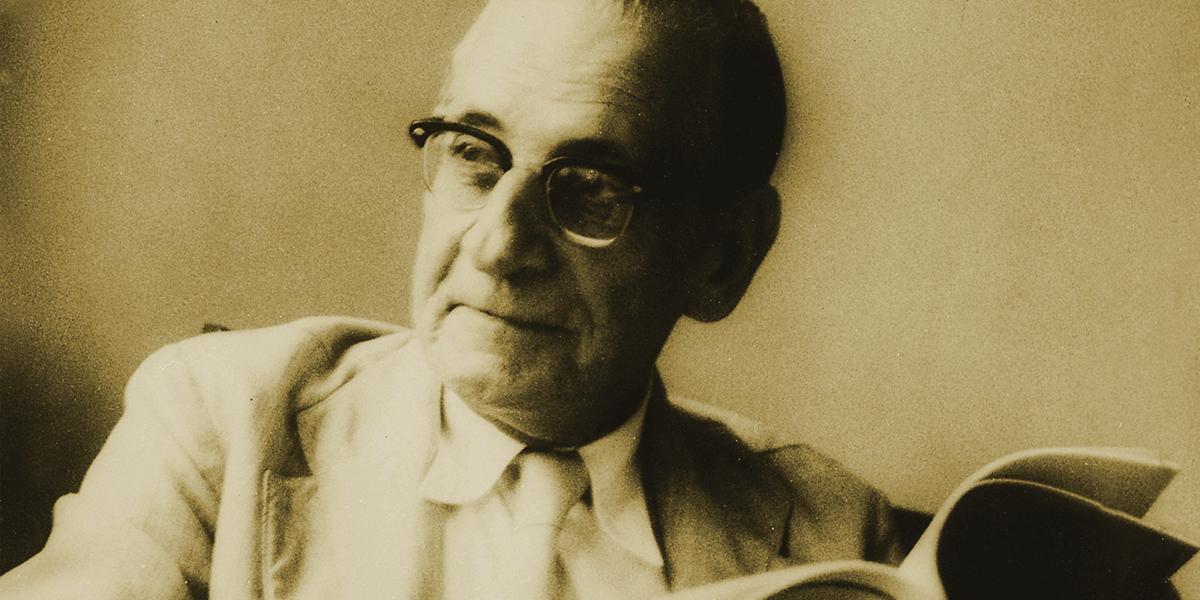

Tall, gaunt and so severely nearsighted that he used to wear eyeglasses while swimming, Grant made a strong impression in Baltimore when he enrolled at Johns Hopkins to study public health under luminaries like William Henry Welch and Sir Arthur Newsholme. He had a bit of the dour Scotsman about him, enlivened with a combustible mix of keen intelligence and self-confidence that could border on brashness. Grant had come to Hopkins after a stint on the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Board, and when Rockefeller executives inquired after him, Welch replied, “He has ability, enthusiasm, industry,” but added that Newsholme thought the student “a little too cock-sure in his judgments.”

Grant survived that job reference, earning a Rockefeller-punched ticket back to China as the first-ever professor of public health at Peking Union Medical College. There, over the next 16 years, he dispelled any doubts about his abilities.

“Some of us consider him the father of primary health care,” says Carl Taylor, professor of International Health. “It was Grant who really developed the foundations for health systems of many developing countries.”

In the period just after World War I, the fledgling field of public health was just beginning to make its mark on medical practice. Great Britain established a Ministry of Health in 1919 and created a new system of grassroots health centers linked with local medical facilities and regional teaching hospitals, all delivering preventive as well as curative services.

Never one to think small, Grant took these bold ideas, conceived for the most developed of nations, and set about applying them in a country with extensive poverty, inadequate sanitation, shoddy infrastructure, widespread illiteracy, an unstable government and no modern health care system to speak of.

Grant had been tagged early on as a “medical Bolshevik” for his embrace of socialized medicine, so it should have surprised no one that upon arriving in Peking he talked straight away with Chinese leaders of his vision for a comprehensive, government-run health system. But news of such conversations nonetheless put administrators at Rockefeller on edge.

“We are a little disturbed at the eagerness with which Doctor Grant is undertaking his duties,” George Vincent, the chairman of the foundation’s China Medical Board, wrote to Welch.

Grant soldiered on, surveying the state of Peking’s public health workforce. He summed up its readiness by quoting a Chinese proverb: “Sitting in a well and attempting to see the whole heavens.” The country had no infrastructure in place to fight major communicable diseases such as typhoid and smallpox, for example, and its infant mortality rate was dismal.

Grant didn’t dismiss the local talent. Born and raised in China, he’d attended a boarding school where students were caned for speaking with Chinese not officially approved by administrators. Such experiences left him with an aversion to the paternalism that veils racist notions of superiority.

While most Westerners then working in China socialized only among themselves, Grant constantly hobnobbed with the locals. His daughter, Betty Austin, recalls a steady stream of Chinese friends arriving at the family home. “They used to call my father ‘Da Beeza,’” she says, or “Big Nose.”

“The foreigner in China is everlastingly thinking in terms of foreigners as being the only worth-while thing in China,” Grant wrote in 1922, “and the foreigner in China has done practically nothing in being able to get the Chinese to adopt his methods.” It would be better, he thought, to support indigenous health campaigns that are “60 percent efficient than Western ones that are 100 percent.”

His grandson, James Grant, studied this period of his grandfather’s life in some detail and he credits John Black Grant’s successes to a “brilliant, synthetic mind.” Mary Brown Bullock, who wrote about Grant in An American Transplant, a history of the Peking Union Medical College, points to Grant’s “unusual intellectual flexibility.” (The writings of both Bullock and James Grant were important sources for this story.)

In Grant’s time at Hopkins, Welch had predicted that he would be “stronger on the administrative side than on the investigative.” And in fact, Grant’s accomplishments in China were as much triumphs of management as of public health practice.

Gathering even basic vital statistics data was a challenge, since dissection was basically banned and autopsies were out of the question. Rather than tilt at the windmill of this ingrained cultural tradition, Grant asked China’s coffin makers to provide a cause of death. He had them stick with familiar folk descriptions. Then he worked up a guide so that medical professionals read a phrase like “witchy wind” as “pneumonia.”

Grant’s first undertaking in China was a Demonstration Health Station operating out of an old temple. Opened in 1925, it served a district of urban Peking with 100,000 residents. While all manner of cultural, political and financial complications surrounded this start-up, Grant never got mired in turf wars—an approach reflected in advice he offered to Shisan Fang, the Station’s director. “You are in possession of an opportunity to have your name go down in the permanent history of China provided you play your cards right,” Grant wrote. “If the playing of such cards should call for some slight and apparent temporary knuckling to inefficient nobodies, whom even the Peking public will have forgotten before they are dead, that is a small price to pay for your immortality.”

The Station was soon delivering modern clinical care to ever-increasing numbers of residents, both at the temple headquarters and at community locations. Health care workers also took educational sessions and preventive measures out into factories and schools. Part of the strategy involved improving sanitation—by establishing a chlorination plant for water, and launching street inspections for sewer and garbage problems. Priority was also placed on slowing the spread of communicable disease, through better reporting, isolation and tracking techniques, as well as health education. Through all these efforts, the target area’s death rate dropped nearly 20 percent—from 22.2 per thousand to 18.2—in less than a decade.

Impressive numbers, but observers were struck even more by the way Grant created a program nearly free of Western fingerprints. Victor Heiser, Rockefeller’s top executive for Asia, noted that Grant’s “push and energy” were crucial to the project, but marveled at how among locals, “the Center is looked upon as purely Chinese and fully under their control and management.”

This was not just a smoke-and-mirror act. With the exception of one head nurse, the Station’s leadership and staff were entirely Chinese. Many of the Peking Union Medical College students who trained at the Station went on to log impressive accomplishments while serving in government public health posts in the decades to come.

One notable example of the way Station initiatives were tailored to local conditions came in obstetrics care, which had long been the province of some 30 local midwives. One of Grant’s former students, Marian Yang, proposed offering a two-month training regimen to the midwives, who were basically starting from scratch when it came to germs and infection and didn’t know the importance of washing hands, towels and equipment.

Frustrations in getting this program off the ground almost drove Yang to quit public health altogether, but Grant talked her in off that ledge. “One cannot expect to have immediate results even when there are revolutions,” he told her, “much less when it is social evolution.”

Yang’s program soon put a serious dent in infant mortality in the Peking district. It was then copied all over the country and grew into a national Midwifery School. The approach survived in China through World War II and the Communist revolution, becoming part of Mao’s famous “barefoot doctors” system.

Writing in 1980, Mary Brown Bullock concluded, “Present-day China’s impressively low infant mortality rate owes a great deal to the pioneering programs” of Grant and Yang.

Grant’s second major undertaking in China moved his model into the rural setting of Ting Hsien (now called Ding Xian), some 200 miles from Peking. For its first two years, this program generally followed the precedents set by the urban station. Then, in 1931, Grant’s protégé C.C. Chen led the Ting Hsien initiative into uncharted territory in partnership with the progressive Mass Education Movement led by Jimmy Yen. After conducting an economic analysis, Chen concluded that rural farmers could afford to spend only about 10 cents a year on modern medical care. How could you make progress while spending $100 a year for every 1,000 residents?

The answer was village health workers, local residents who were armed with a modicum of training, a bare-bones first aid kit and a few essential drugs. They were linked to advice from village health stations and a larger health center in the regional capital. By 1934, 80 village health workers were in place; one review found 95 percent of their treatments to be accurate. Two years later, similar programs were in place in 12 other provinces.

“[H]ealth care coverage had been extended to almost half a million people,” writes Carl Taylor in his book, Just and Lasting Change. “Simple methods that focused on behavior change rather than on curative medicine revolutionized health conditions.”

The Ting Hsien model, too, survived World War II and the Communist revolution to inspire the “barefoot doctors.” Grant was probably right to call it the “first systematic rural health organization” in the world. It inspired groundbreaking public health work in other Asian countries, especially in India and Indonesia.

Grant dubbed his approach “regionalization.” The term may not be much used today, but its elements are at the heart of the “comprehensive primary health care” approach outlined in the famous Alma-Ata Declaration issued by the World Health Organization in 1978.

Ironically, Alma-Ata came out shortly before China ended its “barefoot doctors” system in favor of a free-market approach to health care. Carl Taylor watched the transition while working in the 1980s as UNICEF’s representative to China: “It was so sad to see this marvelous system wiped out. Now China is just as inequitable as the U.S.”

Grant left China in 1937, when the Japanese invaded. His time there makes up only one chapter in a career that took him in the 1940s to India, where he founded the All-India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health, and in the 1950s to Paris, where he directed the European region of Rockefeller’s International Health Division.

The many awards Grant picked up late in his career reflect the level of his achievements in his post-China career. He belongs to France’s Legion of Honor, Finland’s Order of the Lion and Denmark’s Order of the Elephant. In 1960, he won the Lasker Award.

The last chapter of Grant’s career unfolded in Puerto Rico, where he once again set out to implement his regionalization strategies. Macular degeneration had cost Grant his eyesight, and his blindness was a source of enormous frustration to him. “What I remember is his push for speed. He was in a bit of a frenzy; he knew his health wasn’t good,” recalls Thomas Livingston Hall, DrPH ’67, MPH, who worked with Grant there in 1961 and 1962 and now lectures at the Institute for Global Health at the University of California at San Francisco.

Grant didn’t live to see his plans implemented. He slipped into a coma one day in the fall of 1962, awaking briefly on October 18, the day of his death. In that brief moment of consciousness, he had an elliptical exchange with his second wife, Denise Deville, which has since become a cherished bit of family history.

Grant: “Darling, are you there?”

Deville: “I’m here.”

Grant: “It’s not the eye that’s important. It’s only service, positive service.”

Service is something Grant delivered in abundance over the course of his career. In Carl Taylor’s view, Grant’s name is not mentioned often enough among the pantheon of history’s public health heroes. “Nowadays, they always seem to think that whoever did the last project was the one who invented it,” he says. “They don’t give enough credit to John Grant. We’re still trying to work out the ideas he gave us.”