Stress and Brain Power in the Lab

Health officials have long postulated that chronic stress is harmful to your health. A growing body of literature now suggests it may be especially bad for your brain.

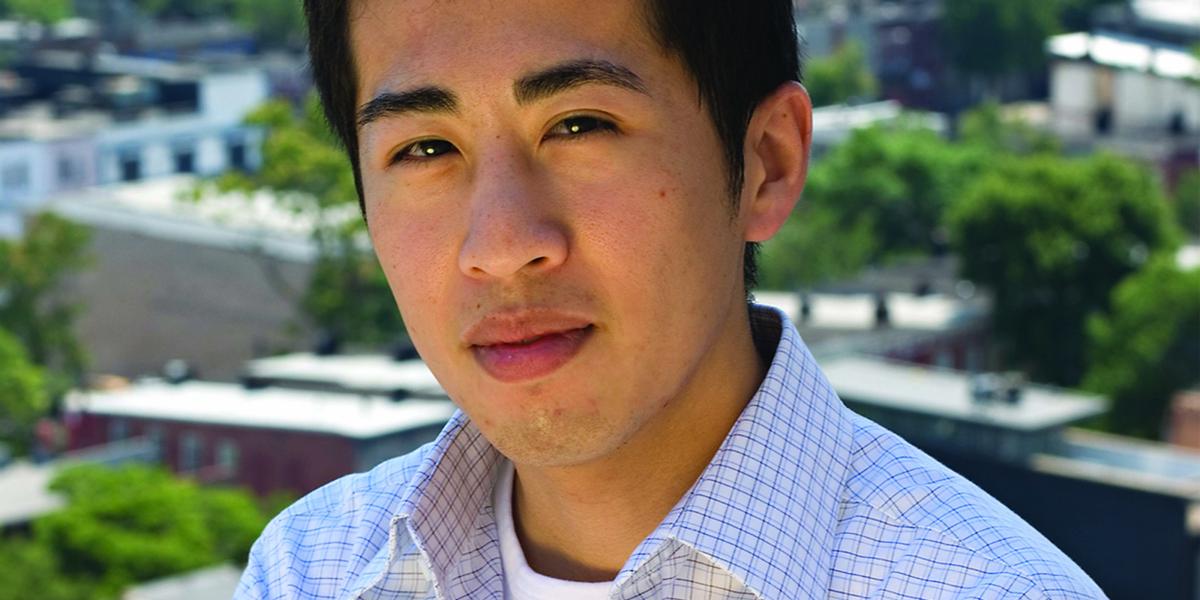

At the Bloomberg School, Brian K. Lee, MHS '06, is finishing one of the most comprehensive studies nationwide of the impact of elevated cortisol on the cognitive functioning of older adults. Lee is working under Brian S. Schwartz MD, MS, professor of Environmental Health Sciences, who is principal investigator on the Baltimore Memory Study (BMS). Lee's paper will be submitted for publication this fall.

Cortisol, a common biomarker for stress, is a hormone produced by the adrenal glands in response to acute and chronic stress. Scientists believe people exposed to chronic environmental stress tend to have elevated levels of cortisol. Animal studies have shown that high cortisol doses are dangerous to the brain. The hormone can contribute to brain atrophy, inhibit the growth and repair of brain cells and increase vulnerability to other neurological insults. Accordingly, researchers believe that people subjected to chronic stress—such as that experienced by those living in hazardous urban neighborhoods—may have elevated cortisol levels and be at increased risk for cognitive decline.

"There's a tremendous range in the trajectory of aging," says Lee, a PhD student in Epidemiology. "We are looking for the reason that we see cognitive decline in some people and not in others. With this study, we believe we've found a significant association" between elevated cortisol and cognitive decline while aging.

For the study, Lee completed a cross-sectional analysis of BMS data, which enrolled 1,140 Baltimore residents, ages 50 to 70. Lee examined the performance of individuals on cognitive tests in relation to cortisol levels obtained from salivary samples. In the study, residents completed 20 cognitive tests at three visits over almost three years. At each visit, they gave researchers four cortisol samples through the day. "The higher the levels of cortisol across the study visit, the worse the person performed on cognitive tests," Lee says.

The study found that elevated cortisol levels in the body corresponded to poorer cognitive functioning in six of seven areas tested. These six areas included language, processing speed, eye-hand coordination, executive functioning, verbal memory and learning, and visual memory and learning.