World War Won

The inside story of smallpox eradication

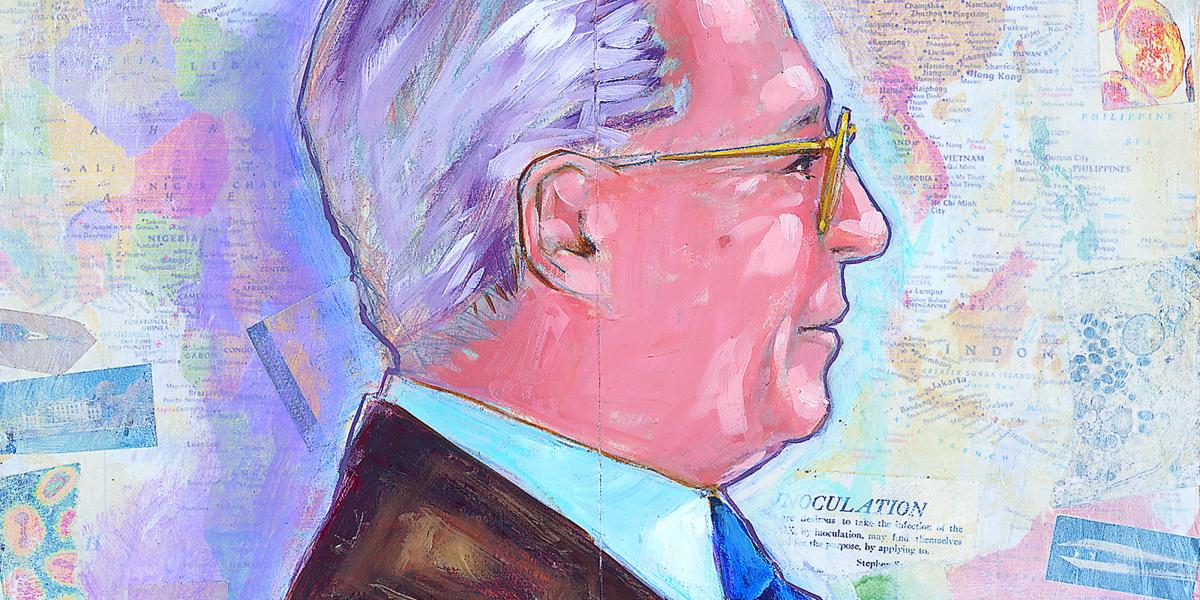

Few believed it was possible. For millennia, the smallpox virus visited misery and death upon humanity, claiming hundreds of millions of lives.Then, in 1966, the World Health Assembly launched the smallpox eradication campaign. D.A. Henderson led the successful global effort, which enlisted more than 100,000 people and demanded extraordinary tenacity, creativity, organizational skills and a willingness to break bureaucratic rules. In the following excerpts from his new book, Smallpox—The Death of a Disease, Henderson, MD, MPH ’60, dean emeritus of the Bloomberg School, shares his insider stories from the consummate public health triumph.

Preface

Smallpox has played a pivotal role in every era of human history. No disease has been so greatly feared or worshipped—no disease has killed so many hundreds of millions of people nor so frequently altered the course of history itself. As I was growing up, however, I knew smallpox only as a name, a disease against which all children had to be vaccinated. That abruptly changed in 1947.

Smallpox suddenly appeared in New York City—two smallpox patients were discovered, but no one knew how or where they had acquired the infection. Their movements were traced, and more smallpox patients were discovered.Emergency vaccination programs began—first for the hospital staff and the patients where the cases were isolated and then for residents of the apartments where they had lived. As more smallpox patients were found, the vaccination program extended to other hospitals and to other parts of the city. Eventually, the source was discovered: a visitor from Mexico who had become ill and died five days after his arrival. During his stay in a hotel, 3,000 people from twenty-eight states had booked rooms. Health staff sought to trace and vaccinate all of them. The city was in turmoil. A decision was finally made to vaccinate the entire urban population. Six million people were vaccinated during a four-week period. This massive effort was the response to an outbreak that consisted of only twelve patients, two of whom died.

Berton Roueché, the respected New Yorker medical writer, vividly described the evolving events, the threat, and the terror in an article “The Man from Mexico.” He quoted from a doctor’s description: “The patient often becomes a dripping, unrecognizable mass of pus by the seventh or eighth day of the eruption. The putrid odor is stifling, the temperature often high (107) has been authoritatively reported), and the patient frequently in a wild state of delirium.” For me, the pervasive concern and fear of smallpox was startling and yet I had known nothing of this disease until its unexpected appearance in New York.

Fourteen years later, in 1961, I would be assigned national responsibility for dealing with smallpox, should it be imported into the United States. My position was chief of the surveillance section at the U.S. Communicable Disease Center (CDC).

It was a time of high anxiety. Major smallpox epidemics were then erupting across India and Pakistan. Travelers flying by jet aircraft were rapidly increasing in number, and some were infected with the smallpox virus.

From 1958 through 1960, the disease had been imported into Europe from Asia six times; eleven more importations occurred in 1961. By the end of 1963, twenty-three importations had resulted in nearly 400 cases. Not surprisingly, we had a number of false alarms in the United States—primarily patients with chicken pox. I assumed that it was only a matter of time before we would have to cope with smallpox.

A Program in Its Infancy

On October 26, 1966, I arrived in Geneva to face stark realities inherent in assuming the position of chief of the Smallpox Eradication Unit—to direct a global program intended to reach more than 1 billion people in fifty countries. I was thirty-eight years old and had a mere ten years of public health experience. Many thought I looked considerably younger than thirty-eight; certainly I lacked the maturity and gravitas expected of a WHO unit chief, few of whom were then under fifty.

Countries, Fiefdoms, and Short-Circuiting the Bureaucracy

The regional offices of WHO were important components of the administrative structure. For smallpox eradication, they were more a hindrance than a help. All WHO member countries belonged to one of the organization’s six regions. In 1967, four of the regions included countries with known endemic smallpox. One regional smallpox eradication program adviser was allotted for each of three—Southeast Asia (SEARO), Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO), and the Americas (PAHO). Two advisers were allotted for the African Region (AFRO)—one for eastern Africa, based in Kenya, and one for western Africa, based in Liberia. The advisers were selected and appointed by each regional director without reference to our unit at headquarters.The regional directors considered themselves all but autonomous. After Dr. Halfdan Mahler became director-general in 1973, he often said to me, “You have to remember that WHO is, in fact, an Association of Regional Offices, not a World Health Organization.”

The regional directors were each elected for four-year terms by a majority vote of that region’s member countries. Gaining or retaining a country’s vote required skillful politics, and such factors inevitably played a role in important decisions such as the selection of qualified staff and allocating of budget funds.

The regional directors interpreted the initiatives of the World Health Assembly as being primarily advisory. Some they accepted, some they ignored, and some they modified to suit their own and the region’s particular needs and agendas.

Given the director-general’s openly expressed skepticism about smallpox eradication, it was not surprising that there was little support for smallpox eradication in the regions. Two regional directors were passively or openly hostile to the program; one largely ignored it; and one actively opposed it. Fortunately, the one who most strongly opposed the eradication program was replaced through election by a strong supporter a year after we began.

The regional offices added a dysfunctional layer of bureaucracy for communications with country program directors and WHO advisers. Recall that at the time of the program, there were no e-mail facilities, no mobile phones, and no fax machines. Telex and ordinary telephone calls were expensive (and not always technically possible). Personal contact and correspondence by mail were our only reliable routes for communication. WHO policy required, however, that all correspondence with countries had to pass through the regional offices. But this was more than simply a routing of memos. For example, if I wanted to communicate with a smallpox program adviser in Uganda, my letter had to go first to the African Regional Office whose office was in Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo. It would be read by one of the staff, who might eventually prepare a draft forwarding memo for the regional director’s signature—a deceptively simple procedure that often required several rewrites and could take weeks. The recipient, the WHO country representative, would then consult with our WHO smallpox eradication adviser. A reply followed this track in reverse.

This bureaucratic tangle ensured that four to five months might elapse between the time I sent a simple query and received a reply—if one came at all. Eventually I resolved the problem by simply sending original copies of memos to the regional office, as directed, and carbon copies directly to the recipient. However, this added another wrinkle because the WHO mail pouch did not carry personal mail and the copies were so regarded. Regular postal service worked reasonably well, although it often cost me 100 to 150 francs a month to send my documents. It was worth it.

The direct system of communication sometimes created its own problems: once we received a telex from Uganda asking that 2 million doses of vaccine be sent urgently. We sent the vaccine by air the following morning. Five months later, the regional office wrote to report an urgent request from Uganda for 2 million doses of vaccine. We did not know whether this was a new request or the one we had dealt with five months previously. (It was the latter.) The policy of quietly short-circuiting the regional office, when necessary, continued for years and, surprisingly, was never questioned, if indeed the regional directors ever learned about the practice.

Indonesia—A Remarkable Achievement with Few Resources

The program began in July 1968 in Java, one of the world’s most densely populated areas. Thirteen “advance teams” were established. Each had a vehicle and was headed by an Indonesian medical officer who had been given a month’s special training. WHO supplemented the medical officer salaries so they could serve full time. The teams’ primary functions were to work with local authorities to promote the vaccination program, to provide some sort of supervision to vaccinators, and to try to establish the regular reporting of cases to the national smallpox program headquarters. At first these activities seemed to have little effect on smallpox incidence. However, as the importance of surveillance containment became apparent, the teams in two of Java’s three provinces cut back on all routine vaccination and undertook special searches in order to find and contain cases.

It was during this period that the first use was made of schoolchildren and teachers to report outbreaks, and the idea of the WHO Smallpox Recognition Card came into being. As the number of smallpox cases declined to low levels in a province, the teams moved on to more heavily afflicted areas. It was a surprise to find that despite the density of population, the spread of smallpox remained concentrated geographically. Long-distance spread to more distant areas was infrequent.

In Indonesia, the reported numbers of cases of smallpox for 1967 and 1968—13,000 and 17,000, respectively—depicted a problem that was much less serious than the program staff had anticipated. [Dr. Jacobus] Keja, then serving as the SEARO regional adviser for smallpox, decided in 1968 to undertake a population-wide survey of facial smallpox scars. From this he could develop an estimate of the actual numbers of cases that had occurred during 1967. He found that the true number was more likely to have been at least 100,000 cases. The minister of health was profoundly skeptical and asked that his own Indonesian statisticians review the data and reach their own conclusions.They concluded that the true number of cases was actually even higher, more likely 200,000 to 500,000 cases. Interest in the program at the highest levels of government soared, and additional Indonesian government resources were quickly made available.

The development of a surveillance system was one of the more remarkable achievements in Indonesia. It became fully effective in early 1970. The architect was an Indonesian medical officer, Dr. A. Karyadi. He standardized reporting forms and established a goal of receiving all reports within two weeks from provinces and within three weeks from the outer islands. This required imagination and innovation.The postal service was limited in its geographic scope and was unreliable at best. But creative methods were found—enlisting bus drivers, military personnel, special messengers, and businessmen as couriers. By September, Karyadi reported that 95 percent of the weekly reports were being received from all reporting sites on two of the main islands. This contrasted to the situation only a year before, in which only half of the units had reported—with delays of twenty-one weeks. In May 1970, he began issuing a weekly surveillance report, much as [statisticianepidemiologist] Leo Morris had done in Brazil.

As the advance teams experienced increasing success, routine vaccination efforts declined, case searches increased in number and intensity, and additional vaccinators were enlisted to help in containment vaccination. What appeared to be the last cases in Indonesia were discovered in December 1971—little more than three years after the program had begun. Four weeks passed without cases, and then 45 cases were notified from a sub-district only 17 miles (twenty-eight kilometers) from the capital. Special teams began a rapid search and vaccination effort, but 160 cases were discovered before the last occurred in late January 1972.

The success of the Indonesian program, given the obstacles and paucity of resources, was a remarkable achievement. International support was minimal, amounting to only $1.3 million (little more than one cent per person); it included 24 vehicles, 430 motorcycles, and 3,100 bicycles. Several of the exceptional senior staff were eventually recruited to serve as WHO advisory staff in other countries. One of them, the Indonesian program director, [Dr. Petrus] Koswara, forty-three years of age, was the only WHO staff member to die while working in the program. He succumbed to a heart attack in 1974 in Ethiopia.

The Eradication-Escalation Strategy

One of our first field operatives in Nigeria was the very tall, irrepressible Dr. William Foege, whom I had recruited from his Lutheran mission post in Eastern Nigeria. Foege had previously worked with me at the CDC, most recently in the smallpox unit, and he welcomed the challenge of the new eradication program. (He was eventually to become director of the CDC and later of the Carter Presidential Center.)

In November 1966, before most personnel and equipment had reached the field, Foege and two CDC staff members arrived in Eastern Nigeria. They soon received reports of smallpox cases from missionaries and quickly worked to control them. Using borrowed motorbikes and a limited supply of vaccine, they successfully contained three outbreaks simply by vaccinating household and village contacts. They discovered that the first cases had come into the area from Northern Nigeria. In an effort to discover other outbreaks, they recruited a missionary-based radio network to help report cases; subsequently, other health units were included in the network.The smallpox cases were occurring primarily along the northern tier of the region, and so, as more vehicles and vaccine became available, they focused on this area.

By the end of May 1967, they had detected and contained 754 cases and vaccinated about 750,000 of the 12 million Eastern Nigeria inhabitants. Cases had rapidly diminished in number, and finally some weeks went by with no new cases being discovered. On May 30, Eastern Nigeria proclaimed itself the independent nation of Biafra. Active fighting broke out, and the CDC team was forced to flee the country. Later, Red Cross workers and others working in Biafra reported that they had encountered no smallpox cases. Smallpox transmission appeared to have been stopped by a vaccination program that had reached less than 10 percent of the population.

Foege concluded that the surveillance-containment component of the eradication strategy could prove to be more effective than we had anticipated that it might be possible to stop transmission even before a mass vaccination campaign could be completed.

A year later, in May 1968, he proposed this to the CDC staff for implementation throughout West Africa. The effort was to be labeled Eradication-Escalation. The one country where implementation of the strategy was delayed was, ironically, Nigeria. There had been serious concern that the Biafran civil war might spread more widely throughout that country and stop activities altogether. Thus, it was decided to put all possible effort into vaccinating as many people as possible as quickly as possible, in order to limit the size of potential subsequent outbreaks should the program be interrupted by war.

Meanwhile, the mass-vaccination programs using the jet injectors had proved to be remarkably effective. Special teams checking on vaccination coverage found that vaccinators were reaching more than 80 percent of the villagers. By September 1968, when the Eradication-Escalation strategy got under way, almost 60 million of the targeted 110 million vaccinations had already been given; fifteen of the twenty countries were free of smallpox. In Nigeria, with nearly half of the West Africa population, smallpox incidence had fallen dramatically. The special strategy did play a significant role, however, in Guinea and Sierra Leone, where operations began a year after the other programs.

The last cases in the whole of West Africa were thought to have occurred in October 1969, less than three years after the program had begun. Until March 1970 surveillance and search operations failed to detect other cases. An evening to celebrate the success of the program was in progress when a report was received of a suspect smallpox case admitted to a hospital in Northern Nigeria. Foster himself drove some two hundred miles to the hospital, confirmed the diagnosis, and undertook a nighttime emergency vaccination program.

Some thirty active and recovering patients came through the line. In all, seventy-five cases were eventually discovered before the outbreak was stopped. The final case occurred in May 1970—the last in West Africa.

A Smallpox Surveillance Team—Courage and Dedication

Under the direction of [Dr. Abdul Mohammed] Darmanger and [Dr. Arcot] Rangaraj, the Afghani field teams became a remarkably dedicated and courageous group. The investigation of a rumored outbreak in a northern mountainous area is illustrative. The team was sent on horseback to investigate but encountered three-foot-deep snow and had to turn back. They tried again by another route but again encountered snow. The horses were abandoned and the team continued on foot for four days to get to the outbreak area. They moved from village to village vaccinating and checking for cases as they went. In all, they spent six weeks in the middle of winter containing the outbreaks. When it was possible to carry out a thorough search of the area in the spring, no subsequent cases of smallpox were found.