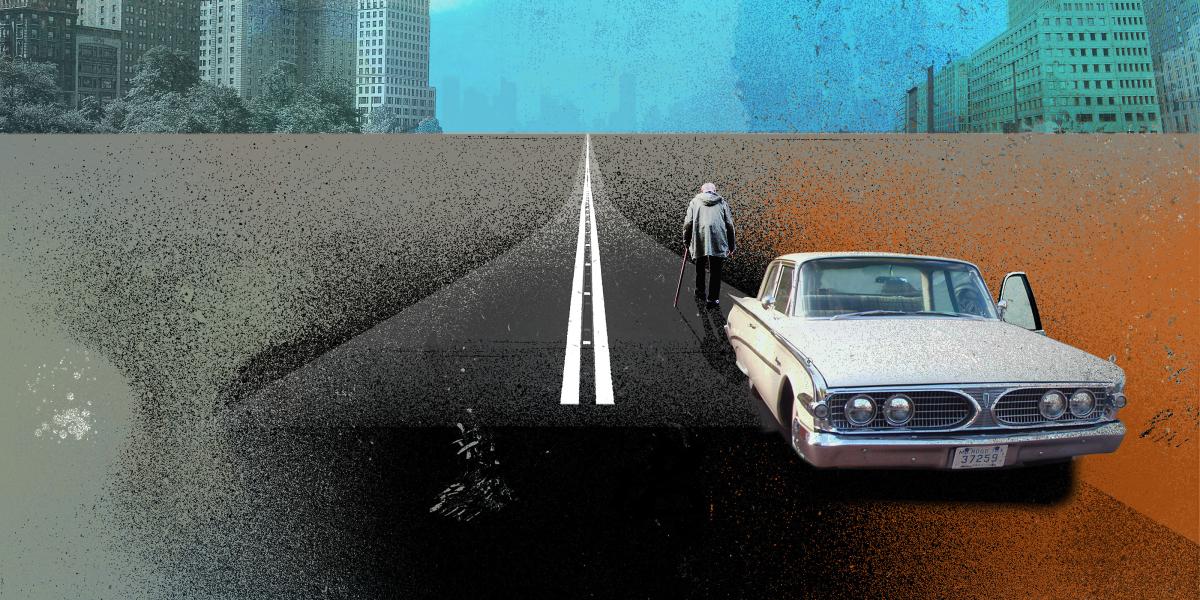

End of the Road

The science of knowing when older drivers need to let go of the wheel

On a spring-like Saturday morning in February of last year, Jeanette Walke drove her silver Honda Civic northwest on University Parkway near Johns Hopkins University’s Homewood campus and made a right turn across a bicycle lane into the driveway of her apartment house. Police say she cut off 20-year-old Nathan Krasnopoler—science fiction fan, chess player, enthusiastic amateur cook and Hopkins computer science student—who was carrying a bag of produce home from the Waverly Farmers Market on his Trek bicycle. A police reconstruction of the accident said Krasnopoler swerved, collided with Walke’s car and was thrown in front of it, trapping him underneath. Badly injured and apparently unable to breathe, he was caught between the searing heat of the engine and the pavement. He was still wearing his bike helmet, according to police, but his lungs had collapsed. His broken glasses were found at the scene.

Walke, then 83 years old, climbed out and sat on a low wall as passers-by gathered. A witness told police she held her purse on her lap and seemed to be staring into space until someone asked her to switch off the engine. “I started to turn into the alley, then I heard a crunch like metal crumbling,” Walke later told police investigators. “Then I saw a limb like an arm and then I saw a head and I stopped and realized that the person was under my car.” By the time Baltimore firefighters managed to pull Krasnopoler out, he had a broken collarbone, fractured ribs, two collapsed lungs and severe burns to the face. He suffered extensive brain damage from a lack of oxygen and died six months later.

While most media reports emphasized Walke’s age—“Elderly Woman Ticketed in Crash with Hopkins Bicyclist” was a typical headline—Walke told police she was in good overall health. She reported having had glaucoma surgery in 2009 in both eyes, but told police she had visited the ophthalmologist the previous month and was given “a good report.” Walke could not be reached for comment, but her attorney says he did not believe her age played any role in the incident.

Still, the tragic death of Nathan Krasnopoler bore some of the hallmarks of collisions involving older motorists. Walke, who was charged with negligent driving, told police she looked but didn’t see Krasnopoler riding in the bike lane on her right as she approached her driveway. “I kept checking,” she said, according to the police investigation. Experts say that drivers older than 80 or so who are involved in collisions are more likely to report never having seen the other vehicle.

In America and affluent societies around the world, driving has come to be regarded not just as a symbol of youth and independence, but perceived as a basic human right. Giving it up can be hard. If we live long enough, most of us will face increasing mental and physical problems that can affect our ability to drive. Yet many older drivers with declining skills fiercely resist giving up their licenses. Meanwhile some studies suggest that giving up driving can increase social isolation, raise the risk of depression and restrict access to health care—though these problems may be aggravated by other age-related health issues.

Researchers are seeking ways to help keep older people behind the wheel for as long as they can drive safely and to prepare them to call it quits if they can no longer do so. The goal: Help governments, families and society improve road safety while respecting the rights of older citizens.

Answers, however, have been elusive. “The evidence is really just not there yet on what policies and programs are most effective, and much more needs to be done in the area of older driver research,” says Andrea Gielen, ScD ’89, ScM ’79, director of the Center for Injury Research and Policy (CIRP).

States grappling with the issue have no clear path ahead, says John Kuo, administrator of Maryland’s Motor Vehicle Administration and the governor’s highway safety coordinator. “There’s no norm or best practice that’s surfacing. This is a national dilemma,” says Kuo. “We must develop a strategy that meets their needs and keeps them safely on our roadways.”

Last year saw the first of the baby boomers turning 65. Older Americans are now the fastest-growing segment of the driving population. Today, about one in seven motorists is age 65 or over. By 2025, that figure will be one in four.

In many ways, older people make ideal drivers, says Vanya Jones, PhD ’06, MPH, an assistant professor in Health, Behavior and Society and a CIRP faculty member. “They don’t drink and drive. They wear their seat belts and tend to stay within the speed limit. They do the good stuff,” says Jones who is a passionate advocate for the elderly. The problem, she and other researchers say, comes when age-related cognitive and physical changes start to affect the complex task of threading a one- or two-ton vehicle through a maze of moving traffic.

Jones is keenly aware of the impact that quitting driving can have on the elderly. She vividly remembers the day her grandfather reached his own painful decision to stop driving. “For me, as a child, he was sort of this larger than life man,” she says. “When he gave up his car, that was one of the few times in his life that I saw him cry.”

Later, while in college in Ohio, she was standing at an intersection when a car hit a pedestrian in front of her. She saw how a life could have been saved if the light had changed a few seconds later or if the driver or pedestrian had slightly altered their behavior. “Personal injuries and motor vehicle crashes are a huge, huge issue for me personally,” she says, saying her concern led to her work with colleagues at CIRP.

Some elderly drivers are as good or better than the average middle-aged motorist. But as we age, researchers say, we experience a gradual erosion of our vision, hearing, response time, mobility, strength and coordination, cognition and judgment. We can also develop a host of age-related illnesses, from glaucoma to diabetes to dementia. To treat what ails us, we may take an array of drugs that separately or in combination can cloud our judgment or slow our reflexes. These changes come sooner for some and later for others, but whenever they come they affect our ability to drive.

“I think there’s often a natural progression as we age,” says Jones, adding that the problem of declining driving skills is “one that we all will probably have to face if we live to be old enough.”

Teenagers and young adults have the worst crash statistics, victims of a cocktail of immaturity and inexperience. But as they spend time behind the wheel, their crash rates go down. Starting around age 75 or so, the process reverses gears, and fatal motor vehicle crashes involving elderly drivers begin to rise sharply. According to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, the crash rate per mile for drivers 85 and older is roughly the same as for teenagers. The rate of fatal collisions per mile traveled is close to double that for teens.

Given the physical effects of age, no one is in greater peril in a crash than an older motorist. Someone 80 years of age or older is six times more likely to die in a collision than someone 35 to 54 years old. Kuo points out that, nationally, while drivers 65 and over rack up just 8 percent of miles traveled, they account for 17 percent of traffic fatalities.

Because of this increased risk of injury-related deaths, Jones says, researchers and traffic safety experts need to find strategies to reduce collisions involving older adults. “You don’t want to be injured in a crash and you don’t want to injure someone else,” she says. “These are really terrifying things.”

The graying of America’s driving population seldom draws much attention until a high-profile tragedy strikes, like the case of George Weller, who in 2003 at age 86 killed 10 and injured 70 when his car barreled through a farmers market in California. In Texas, there were calls for tougher licensing regulations for the elderly after 90-year-old Elizabeth Grimes ran a red light in Dallas in 2006 and slammed into a car driven by 17-year-old student Katie Bolka, who died of her injuries. Likewise, the Krasnopoler case has inspired a call for Maryland to review its policies affecting older drivers.

A recent report by the Trust for America’s Health found that 33 states and Washington, D.C., had some limits for mature drivers, including required vision tests, shorter times between license renewals and limits on online or mailed renewals. That means about a third of states have no such requirements. Some safety activists want to see more restrictive laws on licensing older drivers, including mandatory age-related screening exams or road tests.

Following Nathan’s death in 2011, his grieving parents—lawyer Susan Cohen, an assistant attorney general for Maryland at the time, and her husband, engineer Mitchell Krasnopoler—launched a campaign to advocate new licensing rules. In response to public concern, the state Legislature has directed the MVA to conduct a two-year study of older drivers.

According to the Foundation for Traffic Safety at the American Automobile Association (AAA), Maryland requires drivers over age 40 who are renewing their license by mail to submit a report from a vision specialist and requires new drivers over age 70 to provide a medical report. The Krasnopolers want to go further and require drivers, as they age, to take routine cognitive screening exams that may help spot high-risk motorists before they have catastrophic crashes. But state governments are reluctant to demand additional testing for seniors until there is more data showing that these tests work. The Trust for America’s Health, in a May 2012 report, warned against passage of “reactive, unscientific legislation that overly restricts the driving privileges of older drivers.”

The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) supports tightened testing policies and prelicense screening exams, but not if they’re required based on age. “The only screening method that has been identified that helps reduce crashes among older people is in-person license renewal, and AARP supports in-person renewal across the life span,” says Nancy Thompson, an AARP spokeswoman. “The issue about driving is about health, not age.”

Most older drivers now do what safety experts call “self-regulate,” limiting their driving to match their skills. Edward Ryan, an 89-year-old former engineer at Fort Meade, Maryland, avoids busy streets, the Baltimore Beltway and driving at night. He enjoys short hauls to nearby shopping centers but has no interest in driving on longer trips or in heavy traffic. “I don’t think I miss it, to tell the truth,” he says.

One of Vanya Jones’ chief goals is to find ways to encourage drivers to fine-tune their driving to match their skills and help them prepare to stop driving altogether if the time comes when they are no longer safe on the roads. “We are trying to help adults plan to retire from driving in the same way they would plan to retire from their jobs or change their housing,” she says.

She’s determined, she says, to find an approach to the problem that “honors the individual, that doesn’t disrespect them but also keeps society safe.” And a way to do that, she says, is to find ways to help older adults make their own decisions about driving, including when to stop.

Persuading drivers to take a hard look at their own abilities is not necessarily a straightforward matter.

In a study published in the Journal of Applied Gerontology in December, Jones and a team of researchers from CIRP, the Maryland Highway Safety Office, the Maryland MVA and others administered three standard computer-based cognitive and physical screening exams to 67 older Baltimore County motorists in a laboratory setting. Nine of the drivers, or about 13 percent, were unable to complete or failed two or more of the screening tests and were judged to be at high risk for a crash. (Another 20 were ranked as medium risk because they couldn’t successfully complete one of the screening tests.)

As a group, the nine older drivers judged at high risk had the most trouble with the test that measures the ability to process and sort information.

One of the goals in the study was to see how the high-risk group reacted to being told test results indicated they had a driving-related impairment and should seek medical advice. Jones and her colleagues wanted to learn what participants did with the information, if they would accept the results and seek medical advice or voluntarily stop driving.

From the public health perspective, the results were not encouraging. Of the four drivers who later agreed to in-depth interviews, all said they were uncomfortable with at least one aspect of the testing experience. One told researchers: “Trying to search for a proper word. Disappointed, I guess. Disappointed and [pause] I couldn’t understand why I failed because everybody tells me I’m a good driver.”

Importantly, none of the four who failed the tests disclosed the results to a physician, and only one surrendered his or her license. The one participant who voluntarily gave up driving said: “I think probably subconsciously it was the reason I gave up my car, because I realized that my reflexes were not as good as they were.”

Despite the small sample, Jones says the study demonstrates how difficult it is to deliver unwelcome news to older drivers in a way that encourages them to act. But she wasn’t surprised, because of the importance of driving to many older people.

When it comes to competency behind the wheel, gerontologists say that chronological age isn’t as important as what is called “functional age.” Steven Gambert, MD, director of Geriatric Medicine at the University of Maryland Medical Center and R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center and an authority on the mental and physical effects of aging, recalls testing a former military pilot in his 60s who, as a younger man, had landed a crippled plane armed with a nuclear weapon on the deck of an aircraft carrier. The man’s exceptional skills seemed unaffected by his age. “This guy had superhuman hearing and reflexes,” says Gambert. “He tested off the charts. We couldn’t believe it.”

While many older motorists are highly skilled, Gambert says, others experience a sharp decline starting around age 80. At Shock Trauma, he all too frequently deals with the tragic results.

While Gambert describes himself as an advocate for the elderly, he says that perhaps drivers at a very advanced age, starting in their mid-80s, should be subject to screening that goes beyond an eye test. Drivers with medical conditions or a record of accidents that raises concerns, he says, may need screening earlier. “The reality is, the older you get, probably you’ll get to the point where you’ll need a driver’s assessment,” he says.

Some drivers stay on the road long past the time when they should no longer be behind the wheel. When George W. Rebok, PhD, a professor in Mental Health, was a postdoc studying dementia patients at Hopkins in the 1980s, he discovered that some of his study subjects were driving guided by directions shouted at them by their passengers. Others manipulated the pedals while their spouses steered.

Rebok’s father, Jack Rebok, a retired nuclear power plant engineer, fiercely resisted surrendering his car keys after developing Parkinson’s disease in his early 80s. His family took away his keys, but he had extras hidden around the house. When the family disabled Jack’s beloved Plymouth sedan, a buddy helped him fix it. After Jack Rebok’s doctor reported his declining skills to the state, as required in Pennsylvania, Jack flunked the driver’s test three times and lost his license. But when George saw that his father had visited the barber several miles away, Jack admitted he was driving without a license.

Finally, Jack’s family hid the car and told him it was in the shop for repairs.

While acknowledging such experiences, public health researchers say it is also important to try to keep competent older drivers on the road. Studies have shown that those who stop driving are five times more likely to enter long-term-care facilities and four to six times more likely to die within three years. In part, Rebok says, that’s probably because many drivers quit as their health declines. But he also says that the depression, isolation and loss of control that come with giving up driving may—by themselves—cause health problems. In a 2009 study of 690 current and former drivers published in the Journal of Gerontology, Rebok and other researchers found that at the point older motorists quit driving, they reported a sharp, immediate drop in their physical functioning, social activities and general health. Quitting also accelerated the rate at which their health was declining.

Experts say research is needed into the relationship between giving up driving and household activities, including studies to identify and test coping strategies.

When it comes to cognitive problems, some researchers say new training programs may be able to help older drivers stay safe longer. AARP and AAA offer behind-the-wheel courses designed to help older drivers sharpen their skills. Several commercial firms have produced so-called “brain-training” programs designed to improve driver performance.

In a widely cited study published in Nature in 2010, one team of researchers concluded that thousands of volunteers ages 18 to 60 who played brain-training games online for six weeks did not improve their overall memory or reasoning. Instead, the study found, they improved their skill at taking a particular test.

But Rebok and others believe that an intensive cognitive training program can produce changes that carry over into real life. He is part of a team of researchers participating in a large, long-term, multicenter study called ACTIVE (Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly), which in 2006 reported finding evidence that a 10-week program could improve memory, reasoning and speed of mental processing in older adults. In the study of 2,832 volunteers, participants on average reported improvements in their performance of everyday tasks, including driving, that with booster sessions persisted for up to five years after the training ended. The ACTIVE study’s 10-year follow-up was completed last year and the results have not been published, but Rebok says that the training program had a significant impact on cognitive fitness through at least five years.

“I think the results we were getting with the speed of processing in particular shows a lot of promise in terms of extending driver life spans, letting people stay on the road longer and more safely, and shows evidence of actually reducing crashes,” he says. On the other hand, Rebok says, the severely cognitively impaired may reach a point where “there may not be much you can do to bring [them] back to where they can safely operate a motor vehicle.”

A year after Nathan Krasnopoler’s death, the “ghost bike” that his family bought for $30 and painted white still sits chained to a signpost under an elm tree on the sidewalk a few steps from the driveway where he was injured. Walke, now 84, did not respond to a request for an interview, but her lawyer, Robert H. Bouse Jr., says she was deeply affected by Nathan’s death. “It devastated her, it truly did,” he says.

Walke was cited for negligent driving and failing to yield the right of way to a rider in a bike lane, court records show. She pleaded guilty and was fined $220. The Krasnopolers filed a $10 million lawsuit that Walke settled for what the Krasnopolers’ lawyer called a “substantial” sum. The family says they took legal action only after they learned Walke had continued to drive after the accident, and they insisted she surrender her license as part of the settlement.

Now Cohen has left her job with the state Attorney General’s office and plans to use the money from the lawsuit to set up a nonprofit foundation called Safe Roads USA. Cohen says she will dedicate the rest of her life to an effort to promote research, education and legislation to address the problem of older motorists and traffic safety. “I plan to go for laws across this nation,” she says.