A Sip of Water

When I received the invitation to contribute to this magazine on the topic of death, a flurry of ideas came … and went.

As a clinician and a public health grad, I could have written about health care, death and dollars. All tired topics, all under-whelming. So I decided not to write anything at all.

Until this morning.

I live on a small farm in Maryland with my girlfriend and two dogs. During their early morning walk, the three of them spotted a badly wounded buck inside our field. (For readers abroad, buck is the American term for male deer.) His hind leg had been mangled, likely by a car. He was in pain and terrified. An antler was missing. The dogs were beside themselves, overwhelmed by curiosity, territorialism and the smell of blood.

I was urgently summoned to help contain the dogs and deal with the buck. Grabbing my field jacket and cowboy gloves while still in my pajama pants, I marched with total detachment and strong determination (indispensable personality traits for surgical types like myself) toward the far end of the field to assess the situation. I was convinced it could not possibly be as bad as my girlfriend was describing it. I was wrong.

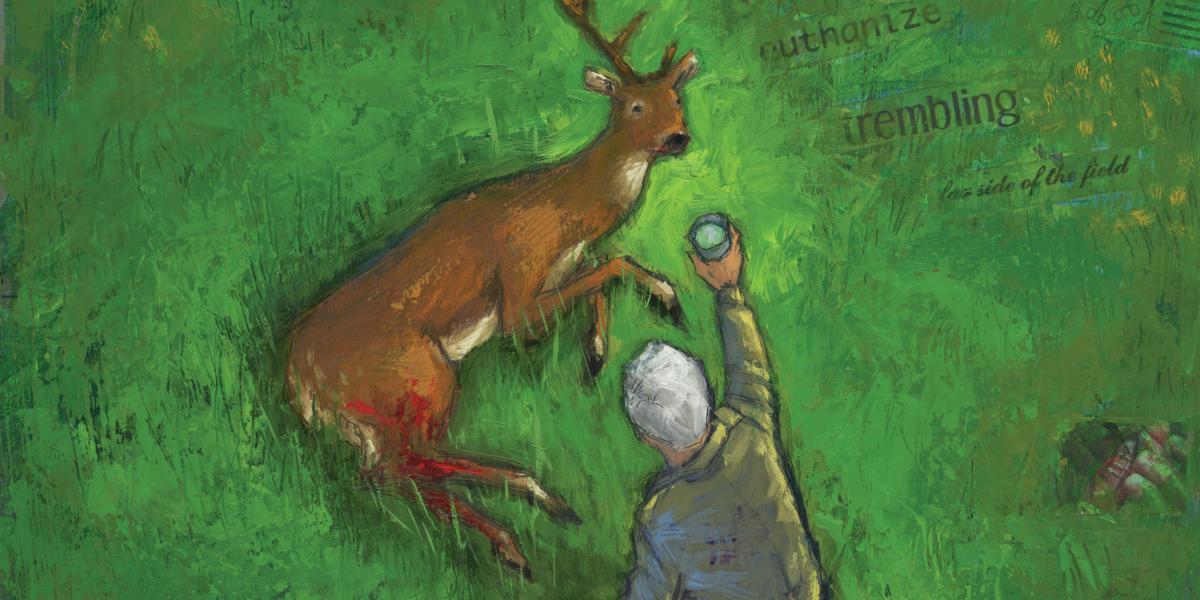

Wounded, trembling, exhausted and with labored breathing, the poor animal raised himself, wobbling back and forth from one end of the field to the other, with me in comic pursuit on the slippery, frosted grass. It was clear the deer needed to be corralled somewhere before we could decide what to do.

Once cornered in the most remote area of the field, the desperate buck looked at both of us and made a final run for the fence, managing to get his head and single antler trapped in the railing. Gently, while leaning my body against his to prevent further damage—to him or us—we lassoed and disengaged his head. Then we walked him like a dog on a leash for a few yards before he fell to the ground, unable to get up.

That’s when the discussion started. I should clarify that my girlfriend has been an orthopedic surgeon for many years, and I have practiced cardiac surgery most of my professional life, so we have strong opinions and a good understanding of what is fixable. She argued for euthanizing him. I contended—I have no idea why, because she was right—that given a safe place, water, wound care and antibiotics, perhaps he could be saved. Obviously, I was no longer objective.

The argument continued, with the buck still lassoed on the ground, until I heard myself saying in a self-delusional but nevertheless convincing tone: “I will not kill this animal as long as there is hope for him to recover.”

Then I added: “He must be thirsty after all the struggle so at least let me get some water before I decide what to do.”

My girlfriend, now late for an appointment, had to leave. Meanwhile, I grabbed a shallow container at the house and collected water from the nearby creek.

When I got back, I realized the deer’s condition had deteriorated. His breathing became faster and deeper. Then it stopped. I stood beside him, in my pajamas, with a water container in my hand, watching life come to its end, feeling awful about my inability to do something else for the beautiful young buck with one antler, on the far side of the field.

It struck me then how often I found myself in similar situations, standing by a patient, in my surgical pajamas, watching life slip away, feeling awful about my inability to do something else; maybe one more drug, one more test, one more procedure.

I couldn’t help thinking that perhaps when my own end is near and inevitable, all I really want, all I will really need is a compassionate human being to order one less test, one less procedure, while taking the time to stand by me and help me take that last sip of water before I die.