Generations

Today’s researchers fulfill the dreams of their pioneering ancestors.

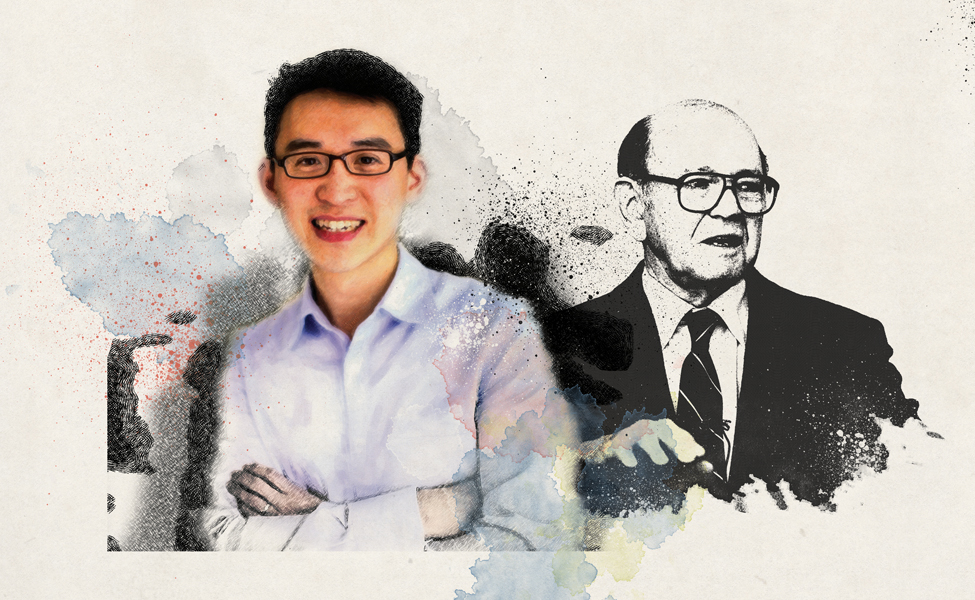

HEALING MENTAL SCARS

Judy Bass

Nearly 40 percent of women in the Democratic Republic of Congo report having experienced sexual violence, a brutal legacy of decades of civil war and ethnic conflict. Medical help of any kind can be hard to come by outside urban centers—and mental health services are generally nonexistent. A staggering amount of trauma, grief, anxiety and depression goes untreated, leading to suicides, social exclusion and family instability.

“Amid poverty and years of ongoing conflict, if there is any help at all available for women it’s primarily services to mitigate the physical scars—there is nothing for the mental scars.” » Judy Bass

For 15 years, associate professor Judy Bass, PhD ’04, MPH, has worked to address the mental health challenges in impoverished and strife-torn countries—an effort that builds on the pioneering advances of Paul V. Lemkau, the founding chair of what is now the School’s Department of Mental Health.

Bass studies the feasibility of adapting culturally relevant group and individual psychotherapies. She also assesses the impact of training local staff with little or no mental health experience to conduct them. In the DRC, the results of that kind of intervention were promising. Studies showed that fewer than 10 percent of women who had received such group therapy still had mental health issues six months afterward.

Similar trials have also been conducted in Kurdistan, Uganda, Burma, Indonesia and Colombia.

Paul V. Lemkau

As a WHO consultant, Paul V. Lemkau, MD, conducted surveys of mental health in Japan, Yugoslavia, Italy, Venezuela and Mexico, and other Latin American countries.

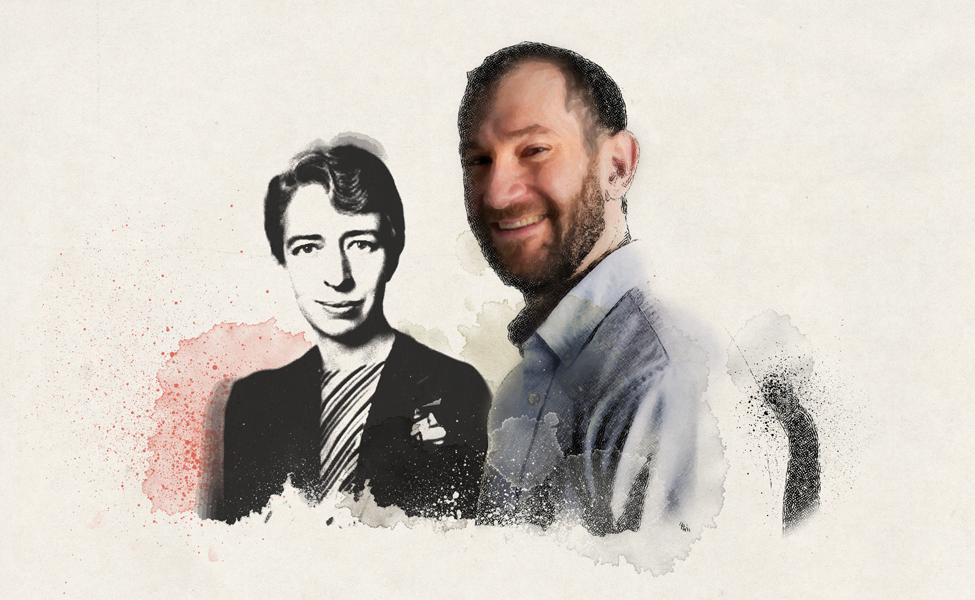

BAPTISM BY FIRE

Darcy Phelan-Emrick

Last April, when violent protests erupted after the death of Freddie Gray, assistant scientist Darcy Phelan-Emrick, DrPH ’09, MHS ’05, was on her way to a meeting in downtown Baltimore. She never made it.

“In the academic setting, you generally do things at your own pace and focus on your own research, but at the health department, if the mayor’s office or health commissioner needs data, you drop what you are doing and figure it out right away" » Darcy Phelan-Emrick

Instead, she heeded the Baltimore City health commissioner’s request to report immediately to the City’s Emergency Operations Center. As parts of Baltimore burned, Phelan-Emrick received a baptism of fire for her new job as chief epidemiologist for Baltimore City.

Phelan-Emrick now spends the bulk of her time at the City health department while also teaching an epidemiology course for the undergraduate public health program. Her work echoes that of Miriam E. Brailey, one of her predecessors whose epidemiological expertise benefited both the School and the health department.

Since last spring, Baltimore’s soaring homicide rate has been an urgent issue for her department, she says. “Baltimore is [experiencing] an historic high in the number of homicides, and we’re treating this violence as an infectious disease—as a public health problem that can be understood and interventions made,” says Phelan-Emrick.

The department oversees the Safe Streets program that supports trained “credible messengers” to mediate disputes that are likely to escalate into shootings. The program is presently moving into the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood, where Gray lived.

Miriam E. Brailey

Miriam E. Brailey, MD, DrPH ’31, was the first female Epidemiology faculty member and first full-time director of the Baltimore health department’s Bureau of Tuberculosis from 1941 to 1950. She authored the first comprehensive study of racial disparities in pediatric tuberculosis incidence and treatment.

THE ANATOMY OF EXPOSURE

Kirsten Koehler

Nearly eight decades after the School’s Anna Baetjer conducted groundbreaking occupational health studies, Kirsten Koehler, PhD, MS, is investigating the risks that welders face on a daily basis.

“Deep in our lungs there are these twists and turns leading into little alveoli. And if you imagine what a piece of foam looks like, it does the same thing. So we can engineer our foam sampler to have characteristics that best mimic what happens in your body.” » Kirsten Koehler

“Welders are exposed to variety of metals—such as chromium, lead and manganese—that are known to be toxic, with some suspected to be related to cancer,” says Koehler, an assistant professor in Environmental Health Sciences.

Mere “exposure” might not tell the whole story of these risks, however. So Koehler has developed a new air sampler that mimics the anatomy of the human lung. The goal: More accurately measure the impact of the actual doses of a hazardous substance to which a worker is exposed.

While current measuring devices simply capture the total concentration of a given substance in the air, Koehler’s new foam-based sampler is imperfect by design. It simulates the human respiratory system, including the partial exhalation of inhaled particles. She expects that her sampler’s findings will be more strongly related to dose and health effects than traditional devices.

Small enough to be worn on a welder’s lapel, the sampler is being tested now to compare its findings with metal concentrations found through worker urine tests.

Anna Baetjer

Anna Baetjer, ScD ’24, linked occupational chromium exposure to cancer, leading to improved workplace standards worldwide. She also established Johns Hopkins’ research and training program in environmental toxicology, one of the nation's first.

TARGETING CELLULAR STRESS

Anthony Leung

Stress in humans is linked to all manner of negative health outcomes, from sleeplessness to depression. Individual cells can experience stress too, and understanding how they express it might lead to breakthrough interventions in treating cancer and other diseases.

“Within the human genome you have a lot of switches—regulators that turn on genes and turn off genes. MicroRNA is one of these master gene regulators. If we can understand how these master regulators are regulated, we may be able to harness this fundamental knowledge to help us with many types of diseases, not just cancer.” » Anthony Leung

“Cancer is usually in a very stressful environment, and that is why we are interested in understanding it for therapy,” says Anthony Leung, PhD, MBiochem. Cancer cells can be “stressed out,” for instance, when they are in tumors far away from blood vessels providing oxygen and nutrients.

His lab uses biochemical, cellular imaging and genomics approaches to study the relationship between stress in cancer cells and microRNAs, a family of small, noncoding ribonucleic acids (RNA). Research shows that more than 90 percent of the human genome is transcribed to RNA—the working copy of our DNA—but most are not encoding for proteins. Leung’s work on these noncoding RNAs follows the pioneering DNA research of Roger Herriott.

Under study is how microRNA may lead stressed cells to have different gene expressions. Leung’s goal is to be able to discover cancer cells by their stress marker and destroy them—and only them—with targeted drugs.

Roger M. Herriott

Roger M. Herriott, PhD, a former Biochemistry chair, introduced the first courses on DNA at Johns Hopkins University. He elucidated the role viruses play in spreading infection by injecting bacteria with their DNA.

SMART SURVEYING

Linnea Zimmerman

More than half of young women in developing countries who want to avoid pregnancy are not using contraception. In some low-income nations, a quarter of girls drop out of school due to unplanned pregnancies.

“A lot of African women are shifting away from traditional family planning methods, such as rhythm method or withdrawal, and using highly effective and long-acting methods.” » Linnea Zimmerman

A global partnership, Family Planning 2020, seeks to improve access to contraception for 120 million women and girls in 65 countries by 2020. But how to tell if the 2020 goal is being met? Think smartphone.

Charged with quantifying the partnership’s successes, Performance Monitoring and Accountability 2020 (PMA2020) embraces mobile technology. While in-country surveys using paper forms once took as long as a year, they now can be done in as little as six weeks, says PMA2020 technical adviser Linnea Zimmerman, PhD ’14, MPH.

“We hire women from the communities in which they live, train them to conduct surveys on smartphones, and then send the information to a cloud server for aggregation,” says Zimmerman, an assistant scientist in Population, Family and Reproductive Health. Her department traces roots to a division founded in the mid-1960s by family planning pioneer Paul Harper.

PMA2020 is also examining GPS data to see how the proximity of family planning delivery points might affect individual women’s use of such services.

Paul Harper

Paul Harper, MD, MPH ’47, assisted in founding Pakistan’s national family planning program and helped gain widespread acceptance for the IUD as a simple, highly effective, inexpensive form of contraception, ideal for population-level campaigns in the developing world.

POWER TO THE TRIAL

Michael Rosenblum

Randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for evaluating new drugs, medical devices, disease prevention interventions, etc. Biostatistics associate professor Michael Rosenblum, PhD, MS, is developing adaptive randomized trials that have the potential to generate stronger evidence about who benefits from an intervention.

“If we can show that a certain group in an ongoing randomized trial is not benefiting, maybe it doesn’t make sense—or is even unethical—to keep enrolling them.” » Michael Rosenblum

“It’s a new approach, motivated by the goals of personalized medicine,” says Rosenblum, the latest in a long line of innovative biostatisticians at the School, including Margaret Merrell, who worked in clinical trials. “But these new designs, in some contexts, provide more power to detect treatment effects.”

Randomized trials seek to determine, on average, if it’s better to give everyone in a target population an intervention—or no one. But this approach can miss subpopulations who benefit more than others or who are harmed by an intervention.

With an adaptive randomized trial, researchers first identify some subpopulations, such as by ranking participants by the severity of their disease, and then monitor the incoming results over time. If an intervention effect differs in a subpopulation compared to all enrollees, enrollment of participants can be adjusted later in the trial based on a preplanned rule.

Rosenblum is developing new adaptive designs and is creating open-source software to help clinical investigators tailor these designs to their scientific questions.

Margaret Merrell

Margaret Merrell, ScD ’30, was the principal statistician for the multisite trials of penicillin treatment of early syphilis, headquartered at the School during World War II.

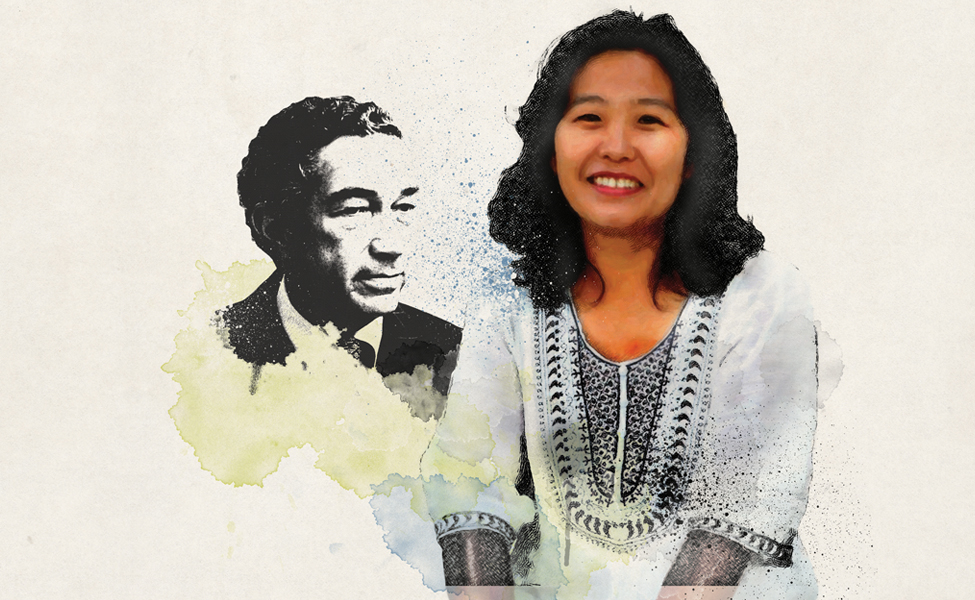

HOPE FOR STUNTED CHILDREN

Yunhee Kang

Nearly half of all children in Malawi have stunted growth due largely to undernourishment. And their stature isn’t all that’s affected. Stunted children also suffer from reduced cognitive development, higher morbidity and increased risk of noncommunicable diseases in their adulthood.

“Stunted mothers can give birth to stunted children, resulting in a vicious cycle.” » Yunhee Kang

In 2014, the Malawian government and a group of NGOs launched a novel prevention program to reduce stunting in young children. The program provides children with nutritional supplements and their mothers with counseling about proper diet and hygiene practices.

The job of supporting data collection, analysis and program evaluation falls on postdoc Yunhee Kang, PhD ’15, MS, fresh off spending four years doing similar work in Ethiopia. “The data include child weight, height, upper-arm circumference and also information about feeding practices and basic household hygiene characteristics,” says Kang, a researcher in International Health’s Program in Human Nutrition, founded in 1976 by George G. Graham.

One year into the project, a mid-impact evaluation of enrolled children shows they have a healthier weight. “This is a good sign as we expect that at the end of three years there may also be a reduction in stunting among program children,” Kang says.

If proven successful, the project may serve as a model for a national implementation.

George G. Graham

George G. Graham, MD, a renowned expert in preventing early childhood malnutrition, established the Institute for Nutrition Research in Lima, Peru, in 1961, which he directed for 29 years.