The Patient Researcher

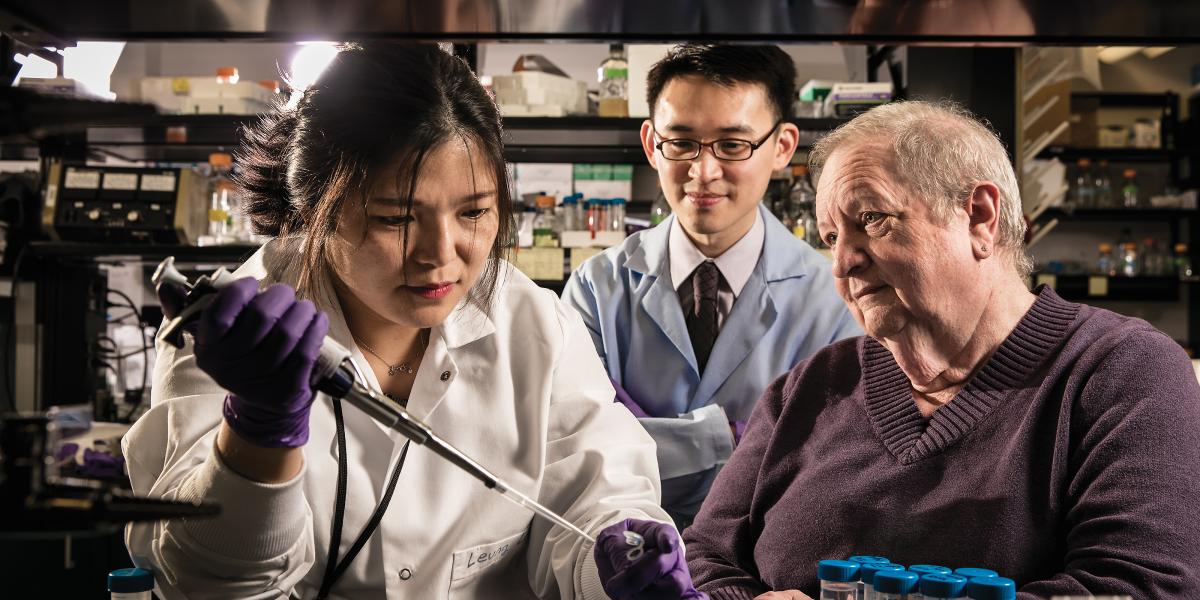

When survivors and scientists meet in Anthony Leung’s lab, it’s clear that cancer research isn’t just about molecules.

Anthony Leung, PhD, pulls on purple gloves and selects from among dishes of live cells—kept active at 37 degrees Celsius—stacked in the incubator.

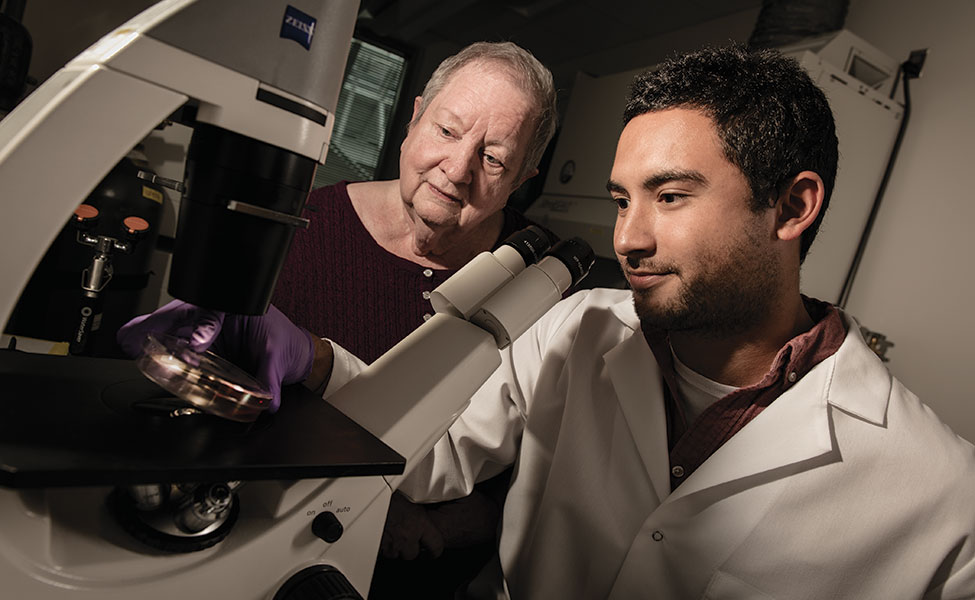

“HeLa,” he says, using scientific shorthand to refer to a human cell line created in 1951 with a tissue sample from a young black Baltimore woman who died from cervical cancer. He places the dish on a microscope and moves aside, inviting a group of visitors—all breast cancer survivors—to come have a look. Angie Cramer, a former steelworker turned nurse who was diagnosed in 2009 with breast cancer, negotiates the narrow aisle between lab benches, bends over and aligns eye to eyepiece.

“Henrietta Lacks’ cells!” Her exclamation is visceral. As if she not only recognizes but also is personally connected to the woman whose cells fuel countless cancer studies around the world.

Indeed, the 57-year-old Cramer—whose sibling had breast cancer, and whose mother and grandmother both died from it—is related to Lacks as a sister in disease, as both are related to the seven other women here today who accepted Leung’s invitation to tour his lab and meet his research team.

Next up to marvel at Lacks’ cells is Judy Ochs. Nineteen years after being diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer, and undergoing bilateral mastectomies and chemotherapy, she developed stage 4 metastatic breast cancer. The aggressive treatments didn’t result in a cancer-free life. Instead, the disease apparently stayed dormant for almost two decades.

“Then it woke up,” says Ochs, who directs the Division of Tobacco Prevention and Control for the Pennsylvania Department of Health.

Ochs’ dear friend Lillie Shockney, director of the Johns Hopkins Breast Center, hovers protectively.

It’s been decades since Ochs first made Shockney laugh, having shared an off-color joke. Decades since the two shared a cancer treatment team, their diseases diagnosed within months of each other. After celebrating many a No-Evidence-of-Disease milestone together, Shockney sees that Ochs, who needed a wheelchair today to get from her car to Leung’s lab, is no longer “NED.”

Shockney also notices that as crowded as this lab is, the survivors all seem to be huddling in tighter together, inching away from the hulking incubator full of proliferating cancer cells, giving it wide berth. All these women—many of them health care professionals—are way too savvy to suspect that mere proximity might put them in danger of the disease reaching out, grabbing them again. But still.

Judy Matthews, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1984 at the age of 31, gingerly approaches the microscope. An executive officer for the U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, Matthews plans on retiring soon, she says, so she can devote herself more fully to advocating for breast cancer research, patients and survivors: “That’s where my heart is.”

Breast cancer is by far the most common cancer in women worldwide with nearly 1.7 million new cases diagnosed per year. Lillie, Judy, Angie and the five others visiting Leung’s lab are among 12.4 percent of women in the U.S. who will be diagnosed with breast cancer. These survivors want cures for themselves, of course, but more than that, they fervently hope their daughters, granddaughters and great granddaughters will be spared this awful diagnosis.

Cancer has claimed these women’s body parts; at times, it's consumed their souls. They are intimate with this disease. And yet, until now, none has seen their nemesis magnified, up close and personal as the cells go about their business, replicating themselves every 24 hours.

Paired with each one of the eight cancer survivors crammed in this lab is a young basic scientist who, under Leung’s tutelage, has logged long and often frustrating hours examining cancer cells to figure out how to turn off their switches and prevent them from replicating. Postdoctoral researcher Hyunju Ryu, for example, knows cancer cells’ molecular make-up, their intricate mechanisms. But until today, she’s never known someone battling the disease, never talked to a real live person who stands to benefit from her painstaking work at the bench.

A high-tech polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine hums in the background, amplifying DNA to detect genes of interest as Leung addresses the group: “I’m the PI,” he says, “the principal investigator. I’m this lab’s equivalent of a CEO; that is, chief explaining officer.”

The gist of this mid-August meeting, he explains, is to facilitate a rare conversation between what he stiltedly refers to as “different stakeholders.”

Clearly it’s not easy, even for someone so earnest and brilliant, to jettison all the jargon. But Leung persists. He’s on a mission.

One of his aims is to educate these breast cancer survivors and convert them into informed and vocal advocates of research. He seeks to align expectations and limitations. Possibly even offer some hope, if not for these women, then for their nieces, neighbors, granddaughters.

In turn, he’s asking them to dig deep. To be candid about living and dying. To give voice to quality-of-life issues. If the standard treatment extends survival by months, or maybe years, but leaves a patient unable to live her life in ways that are important to her, is it worth it? Are there alternatives? He wants their insight to help him determine which scientific paths are most worthy of exploration, given the limits of time and funding.

Not least, he seeks inspiration and motivation for his young team. As the scientist responsible for setting the team’s agenda and securing funding, he wants his researchers to remember these survivors’ faces and recall the dreams of real, live human beneficiaries of bench research—especially when the basic science slog leads to inevitable dead ends and disappointments.

This line of communication, Leung insists, is “the missing link.”

“We will learn what is important to you,” he tells the survivors—each and every one of whom says it is vital to have hope, and insists that Leung’s team gives them that. “And in turn, we’ll let you know what our research is all about.”

THE MYSTERIES OF PARP

Today’s meeting of “different stakeholders” is the culmination of a rare partnership that began a few years ago.

Leung, an assistant professor in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, was in the midst of writing a proposal in the fall of 2013 for a Susan G. Komen grant. An optional requirement—which he felt compelled to complete, given the increasingly competitive jockeying by his colleagues for research dollars—stumped him: “Engage a patient advocate in the research project.” A patient advocate?

What in the world?

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Leung studied biochemistry at the University of Oxford and then was a postdoc investigating gene regulation at MIT before joining the Bloomberg School faculty in 2011. His world was proteomics—the study of proteins—and mass spectrometry. As the most powerful proteomics tool available, mass spec can distinguish between the masses of molecules that differ by only parts per million—an important advantage if your business is deducing the chemical formulas of proteins and protein modifications that constitute cells.

His preoccupation was the mysteries of PARP—short for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase—not maladies of people.

PARP, an enzyme with the ability to modify proteins that are important for DNA repair, held and still holds endless fascination for him. What scientist wouldn’t be lured down the PARP rabbit hole once they understood that when the DNA of cells—no matter whether they are healthy or cancerous—is damaged (maybe by the sun or smoking, for instance) PARP helps to repair it. PARP has the ability to make faulty DNA functional again by adding a chemical group called ADP-ribose onto a protein.

That intriguing biological plot thickens, of course.

PARP has its foes: Rival synthetic molecules that prevent PARP from modifying proteins. The result is that DNA repair can’t happen.

These so-called PARP inhibitors currently are at the cutting edge of targeted cancer therapies. In cancer treatment, blocking PARP may help keep cancer cells from repairing their damaged DNA, causing them to die. Inhibition of PARPs is a promising strategy for targeting cancers with defective DNA-damage repair, including the notorious BRCA mutation–associated breast cancers. With several PARP inhibitors currently in clinical trials and already approved by FDA, the race is on to improve treatment efficacy and reduce their toxicity.

When Leung started his lab in 2011, no methods existed for detecting where PARP adds the chemical modifications onto proteins. So, he set out to create a groundbreaking basic science tool. Now that his team has developed a protocol for identifying the sites of modifications generated by PARP, he’s figuring out ways to apply it.

By using this mass spec–based method, Leung believes they can identify PARP activity. Currently, they are looking at specific locations on proteins where PARP adds the modification. The goal is finding a biomarker for cancers sensitive to PARP inhibitors—a scientific signpost showing which patients will respond to various PARP inhibitors.

That’s how Leung, a basic scientist, found himself three years ago in search of a breast cancer patient advocate. When he reached out to Sara Sukumar at the Breast Cancer Program at the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, she had a definitive reply:

“Lillie, of course.”

Like Cher or Bono, Lillie needs no surname. In fact, Lillie Shockney, MAS, is among the top five names worldwide associated with breast cancer. A registered nurse and a University Distinguished Service Professor of Breast Cancer who directs Cancer Survivorship Programs at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Lillie Shockney identifies, above all, as a cancer survivor. Leung emailed her.

“Come on over,” she replied.

A TRANSFORMED WOMAN

Leung has a restless energy. He was unfazed by the chasm known as Wolfe Street that separates basic researchers in public health from practitioners of clinical medicine. His self-described “Hong Kong gait” is befitting of racewalkers. Or young PIs with no time to spare. It takes Leung less than 15 minutes to travel from his lab on the eighth floor of the Bloomberg School to Lillie’s office on the sixth floor of the Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Carnegie building.

Her workplace—ground zero for breast cancer patients and survivors—was foreign terrain to Leung, whose lab (although he describes it as “a second home”) is spare and strategic: measuring equipment to the left, freezers to the right.

It was as if he had left Iceland and arrived in Italy.

Scattered about on Lillie’s shelves were sea glass and shells. A corked ceramic jar proclaimed “Hidden Strength.” On unabashed display was her penchant for Harley Davidson motorcycles. Her coffee cup, a gift from Judy Ochs, espoused the mantra: Slow down, calm down, don’t worry, don’t hurry....

Despite his urgency to complete his proposal, Leung found himself drawn in to Lillie’s world—as if she exerted a gravitational pull. Mermaid tchotchkes of every shape and size basked in bare-breasted abandon, competing with cards, medals, certificates and awards, all swirling about—a gold and crystal ocean of achievement, gleaming with gratitude.

Everywhere was evidence that cancer survivors are grateful she’s advocating for them, like the patient whose doc originally prescribed a type of chemotherapy that likely would have given her the shakes and robbed her of her dream to play concert piano. It was Lillie who urged the physician to find an alternative, insisting, “We don’t want her to sacrifice anything else to this disease.”

Lillie, who speaks from experience, shared her story with Leung.

In 1992, when she had her first mastectomy, she thought of it as an amputation. Her husband, Al, a truck driver, helped her reframe what was a frightening and emotionally charged experience into something radically different.

"To meet a person who is in need changes your perspective. It makes our research real and gives us a sense of urgency."

He convinced her that the mastectomy was, in fact, nothing less than transformation surgery. A nonmedical guy’s guy if ever there was one, Al helped her spin it into a positive. Not a loss, but a win. He didn’t pity her. He congratulated her.

In his eyes—and suddenly in hers, too—she was not a victim. She was a survivor.

She looked down. She didn’t see the breast gone. She saw the cancer gone.

It was profound. It was magic! She had to tell everyone.

Enthusiastically espousing Al’s wisdom ever since, she has gained support for her view all over the world, most recently during a conference on breast cancer care in Guangzhou, China. With absolute certainty, she greeted one patient after another, “You’re a transformed woman! Congratulations!” Meanwhile, she invites researchers and caregivers to get on board with an empowering philosophy: “We don’t want the patient missing out on a life that has been saved. There is no time for bad side effects from drugs that will rob them of life.

“If you always focus on the patient, everything will be right.”

A SCIENTIST WHO'S INSPIRED

It’s unusual for a basic scientist to spend time focusing on patients. Some scientists might argue it’s not their job. That they don’t have access or time for distractions from their real work. Leung—winner of a 2016 Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society, a 2015 Johns Hopkins Catalyst Award and a 2013 Bloomberg School Faculty Innovation Award—begs to differ. So does Pierre A. Coulombe, PhD, E.V. McCollum Professor and Chair, who describes Leung as “a special talent as a basic researcher connected to the reality of patients.” “Various funding agencies are now adding that patient engagement dimension, with the leadership coming from private foundations,” Coulombe observes. “But it’s not mainstream yet.”

As a young PI whose lab is full of raw talent—and whose plan is to arrange future gatherings between his team and Lillie’s—Leung stands to have far-reaching influence. You might not expect a self-described “mass spec guy” like PhD student Lyle McPherson to appreciate a mentor who melds molecular biology with patients’ emotions. But clearly, he does.

“Anthony is a scientist who’s inspired,” McPherson says. “He’s always thinking of ways to push the boundary. He has a good handle on what is high impact and where a field is at; of knowing what is the big question in a particular field, and are we capable of answering it.”

After the survivors’ lab visit, Lillie asks Leung’s team members to describe him in one word.

“Creative.”

“Thoughtful.”

“Extremely dedicated.”

“Supportive.”

“Persistent.”

“Driven.”

“Passionate.”

Lillie feels herself filling with pride and hope—not that she hears anything that she didn’t sense during her first meeting with Leung in 2013 or that was further confirmed in September of 2015. That’s when she invited him to present his research during a survivor-volunteer dinner she had organized.

Among the women attending that night was Elaine Everett who had come to say goodbye to the group. Weeks later, she would die from her breast cancer. Lillie snapped a photo of Leung listening to Everett’s story and sent it to the researcher.

Ever since, it’s been hanging in his office, along with pictures of his two mentors, Nobel laureate Phillip Sharp and Angus Lamond; his parents, Maureen and Andrew; his wife, Tun-Han; and his kids, Oliver, Ellie, Tobey, and Zoe. They all have faces and names, of course. His research also has a face and a name: Elaine. “She was diagnosed with cancer and treated with tamoxifen, a staple for breast cancer,” Leung says of Everett. “She became resistant to the drug. Recently, part of my lab, in addition to investigating PARP, has been looking into the question of tamoxifen resistance. Is there a way to conquer it?

“I keep Elaine’s photo to remind myself and my team that our questions are not theoretical. Sometimes we bench scientists and our students miss that point. To meet a person who is in need changes your perspective. It makes our research real and gives us a sense of urgency. I want my students to know that their work here is not just about getting a PhD or moving to the next stage of a career.

“This,” he says, indicating the picture of him and Elaine, “is the missing piece in the whole equation.”