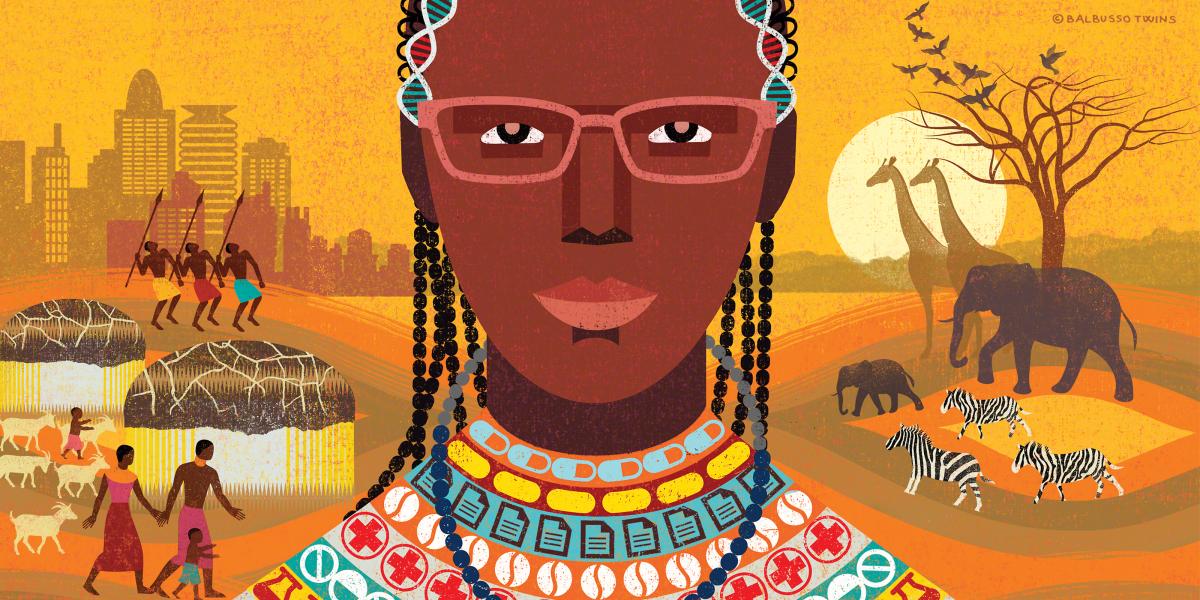

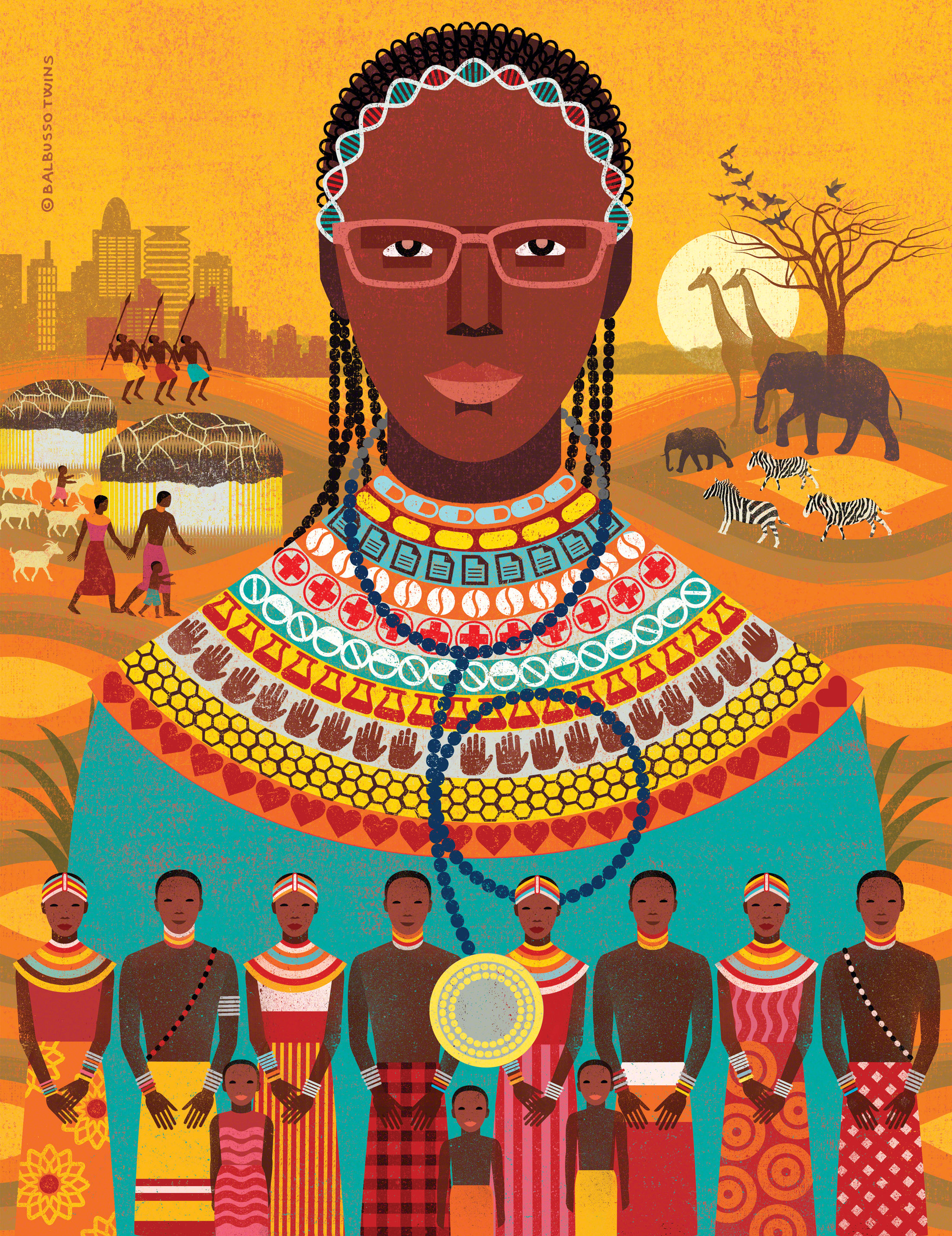

Lesson of the Goat’s Tail

A remote community taught me skills I couldn’t learn in medical school.

It was 2016, and the Kenyan government had released the postings of newly graduated medical officers. It’s an arbitrary allocation: Take a list of names, take a list of places that need doctors and put them together. I ended up in a place called Samburu, 350 kilometers from Nairobi.

I’m a city girl. I grew up in Nairobi; I went to medical school in Nairobi. During my first year of supervised medical training in Kijabe, about 50 kilometers away, I’d go back to Nairobi as often as I could to see a movie or eat out at a restaurant.

When I was posted to Samburu, I thought, “Well, I’m adventurous. No big deal. I’m going to serve my people.”

The first 250 kilometers on the way to Samburu look like the rest of Kenya, with cities and paved roads. And then you transition into a world where small boys herd large numbers of goats on the side of the road. On the last 100-kilometer stretch, the odds were equal of finding a drivable road or one made impassable by the rains.

And then this city girl was transplanted into the Samburu community, where people practice traditions thousands of years old. They do not wear modern clothes; they do not speak the national language. Most people do not live in permanent structures, and they still hold dear their cattle herds. That is their currency. That’s what’s important to them.

I’d been trained—five years of medical school followed by a one-year internship at AIC Kijabe Hospital, a really good center—so I was ready. I was ready to make diagnoses, write prescriptions and treat people.

But first, I had to learn a different set of skills.

For example, I had to learn to ask how long it had taken for a particular goat’s tail to dry out. As part of their burial practices, the Samburu community holds a ceremony to usher the dead into their next life. Part of the ceremony involves tying a goat’s tail around the person’s wrist.

Why would that be important to a doctor?

Because that’s how my stroke patients presented. Their relatives perform the ceremony shortly after the stroke, in anticipation of the patient passing away. If the patient survived, they’d bring them to the hospital.

I needed to know how long ago they had the stroke, which was not something the patients or their relatives were always willing or able to share. But if I could get someone to tell me how long the goat’s tail had been around their wrist, I could tell how long ago they had had the stroke and then develop an appropriate treatment plan.

Instead of asking when the patient got sick, I learned to ask another local person in the hospital wards, “How long has it taken for that goat tail to be that dry?” To give my stroke patients a comprehensive diagnosis, I first had to understand their culture.

This lesson was reinforced by another patient, a 70-year-old woman with a myriad of symptoms. I conducted an examination and ordered blood tests, but nothing tied her symptoms together.

The next morning, I had a ward round with my consultant (in the U.S., this would be the attending physician). I presented my workup and explained that I hadn’t been able to come up with a firm diagnosis. He looked at me, looked at her, and then said, “Oh, grandma, you’re a traditional birth attendant,” which he could tell from the beading she wore. Immediately, I saw the connection.

This 70-year-old lady had HIV. As a traditional birth attendant, she likely had provided care to someone without wearing gloves. I had ordered an HIV test with her earlier labs. When the results came in, the diagnosis was confirmed.

I’ll carry these lessons and many more as I continue my global health journey. It is only by understanding the realities and cultures of the people we serve that we can provide them the care they need and the kind of help they deserve.

Waruguru Wanjau, MBChB, is a current MPH student at the School. This essay was adapted from her September 2017 Alumni Day talk during “Stoop Stories: The Good Fight: Stories About Being a Public Health Advocate.”