Countering the Infodemic

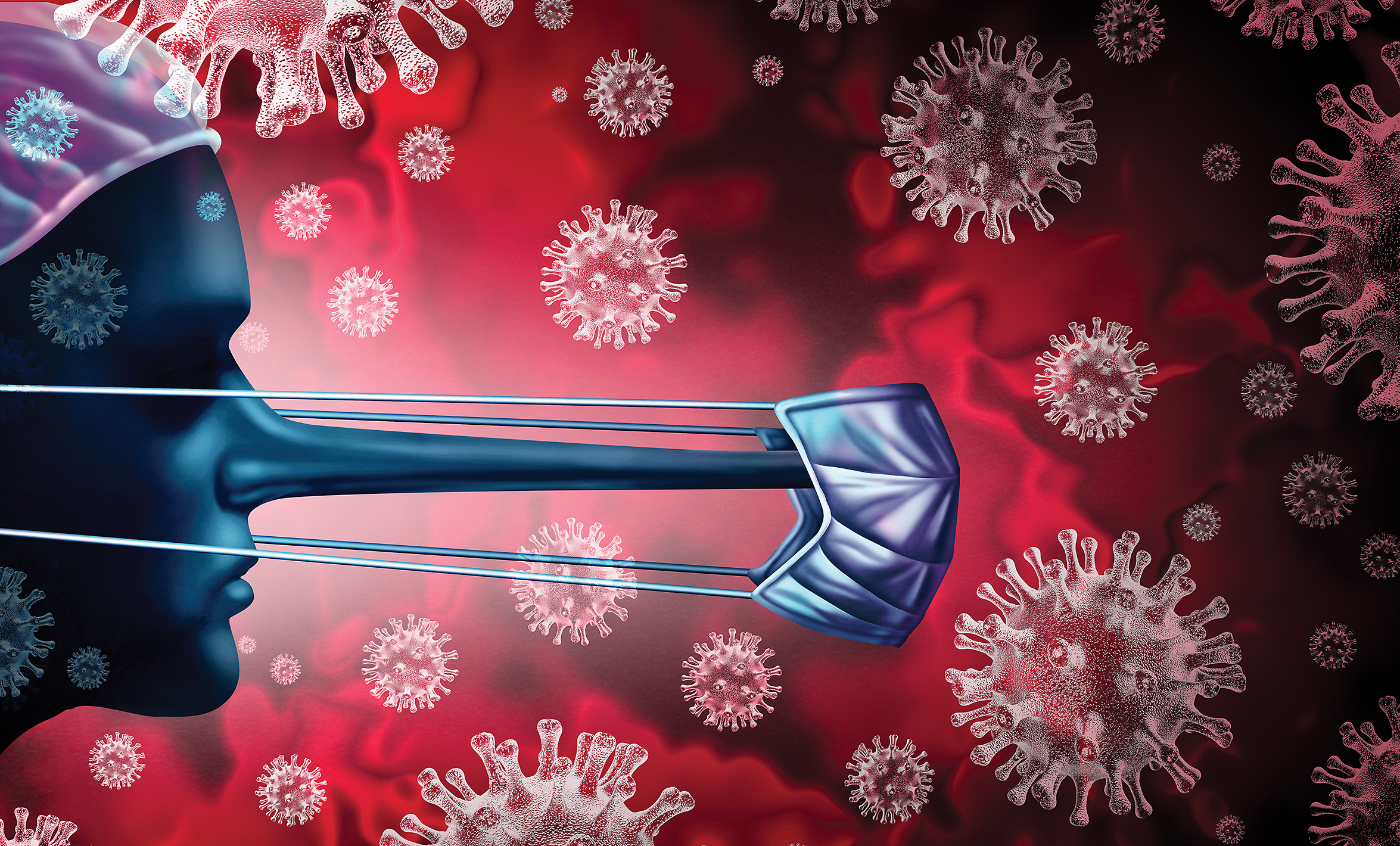

Misinformation about SARS-CoV-2 is as contagious as the virus itself.

In mid-March, reports of mysterious illnesses and deaths began leaking out of Iran. But the cause wasn’t COVID-19—at least not directly.

Earlier in the month, rumors began circulating on social media in the Islamic Republic (one of the countries hardest hit by the novel coronavirus) that some people had cured themselves of COVID-19 by drinking ethanol, also called grain alcohol. Because alcoholic beverages are illegal in Iran, the frightened public instead obtained their liquor from bootleggers or tried to make it at home. Some of the batches were contaminated with methanol, which is far more toxic than ethanol. Consuming even small amounts of methanol can cause blindness, kidney failure, and death. In just two weeks, more than 1,000 people were sickened and over 300 died, according to Iranian media reports.

This is a classic—and deadly—case of misinformation, according to Tara Kirk Sell, PhD’16, MA, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and an assistant professor in Environmental Health and Engineering. Falsehoods, which can range from deliberate lies to genuine confusion and errors, often travel alongside novel threats like COVID-19. But the problem has been so prevalent with the coronavirus pandemic that the WHO has called this swirl of online falsehoods an “infodemic.”

“There’s a lot more misinformation out there than we’re used to. All of that detracts from our ability to come up with constructive solutions,” says Amesh Adalja, MD, also a senior scholar at the Center for Health Security.

Adalja says he’s spending a lot of time convincing people that the virus didn’t originate in a lab or that aiming a hair dryer up their nose will not save them from the novel coronavirus. “The whole pandemic has been polluted with [misinformation],” he says.

Experts like Sell divide misinformation into four different categories:

- False cures. Influencers on social media have been promoting a “miracle mineral supplement” to cure coronavirus that, in actuality, contains dilute bleach, a known toxin.

- Conspiracies. Accusations that the virus may have originated in a bioweapons lab from any number of countries have emerged on Twitter, despite conclusive evidence from scientists that SARS-CoV-2 has a natural origin.

- Scapegoating. Some media outlets and politicians continue to refer to SARS-CoV-2 as the “Chinese virus” or “Chinese disease.”

- Misinformation about the disease. In the early days of the pandemic, some politicians and intelligence officials dismissed COVID-19 as “just the flu,” despite data from Wuhan, China, showing otherwise.

Some perpetrators of misinformation claim what they’re sharing is from a reliable source. One such example is a post circulating incorrect information on coronavirus prevention that claimed to be written by a Johns Hopkins immunologist. But such credentials aren’t always necessary. One of the most challenging aspects of this infodemic is that, on social media, the bar for what constitutes an expert is very low, says Susan Krenn, executive director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs. As a result, she says, “even the definition of what’s considered true or a fact has shifted a bit.”

Fighting misinformation could prove as important as other steps people are taking to flatten the curve.

But when this misinformation comes from historically trustworthy sources and public figures, “it gives it a life it doesn’t deserve,” Adalja says.

Much of this misinformation is underlaid with political meaning. Long after scientists were urging action to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus, many conservative pundits and like-minded officials continued to dismiss the looming threat. Krenn saw similar issues in the 2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Politicians often tried to blame the virus and missteps with its containment on their rivals or enemies, either within the state or in other countries—something that is also happening in the current pandemic.

“Misinformation can be weaponized as a political tool, both by our own politicians and by enemies to spread discord,” Krenn says.

The good news is that there are potential solutions to the infodemic. The popularization of “flattening the curve” images worked because they were easy to remember and share. Pairing the truth with an emotional appeal can also help people change their minds more readily, Krenn says. The key is to make it personal so people can connect with the message. Without that, “the information is over my shoulder and it’s gone,” she says.

Take the antimalaria drug chloroquine touted as a “miracle cure,” despite the lack of reliable evidence supporting its efficacy against SARS-CoV-2. Instead of simply saying the claim isn’t true, a more effective message, says Krenn, is to express understanding of the desire for a treatment but also a concern for people experiencing severe, even deadly, side effects of a drug that may not even work.

People are more receptive to hearing evidence when it comes from a messenger who is already trusted by the community. These messengers must be able to share information that is clear and understandable—and they also need to share what they don’t know, Sell says. This is crucial to combating misinformation and helping people cope in an environment where the scope of what’s known is constantly shifting. Otherwise, she points out, “there’s a lot of space for hucksters to take advantage of people.”

To fight the infodemic, researchers need to understand who people do—and don’t—trust. In Krenn’s Ebola work, she found that messages from government spokespeople often backfired because few people trusted these officials.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, one voice that has earned trust on both sides of the aisle is NIAID director Anthony Fauci. His clear presentation of what’s known and unknown, combined with his long history as an effective civil servant and scientist, has cemented Fauci’s appeal. It seems counterintuitive, but a spokesperson’s ability to say “I don’t know” and to convey uncertainty can make them more believable to people, Sell says. The ability of Fauci and other public health officials to communicate facts in clear language that’s easy to understand can go a long way in bridging the information gap that can exist between scientific knowledge and the general public, Krenn says.

Fighting misinformation could prove as important as other steps people are taking to flatten the curve. Communication, says Sell, is critical in public health and health security. “We can have the best vaccine, but if no one takes it, it doesn’t help,” she says.