COVID-19 Real-Time Response

From a virtual ICU to a Navajo Nation quarantine, public health experts solve novel challenges.

Inside the Virtual ICU

The intensive care nurse stands inside a plexiglass box mounted on casters, something like a phone booth that rolls. Two sleeves through the glass allow her to attend to the patient. The nurse doesn’t need a mask and won’t have to change protective gear between COVID-19 patients. Cameras enable two doctors inside the room to work with five doctors far away.

This is the “virtual ICU,” the present and future of patient care in a pandemic.

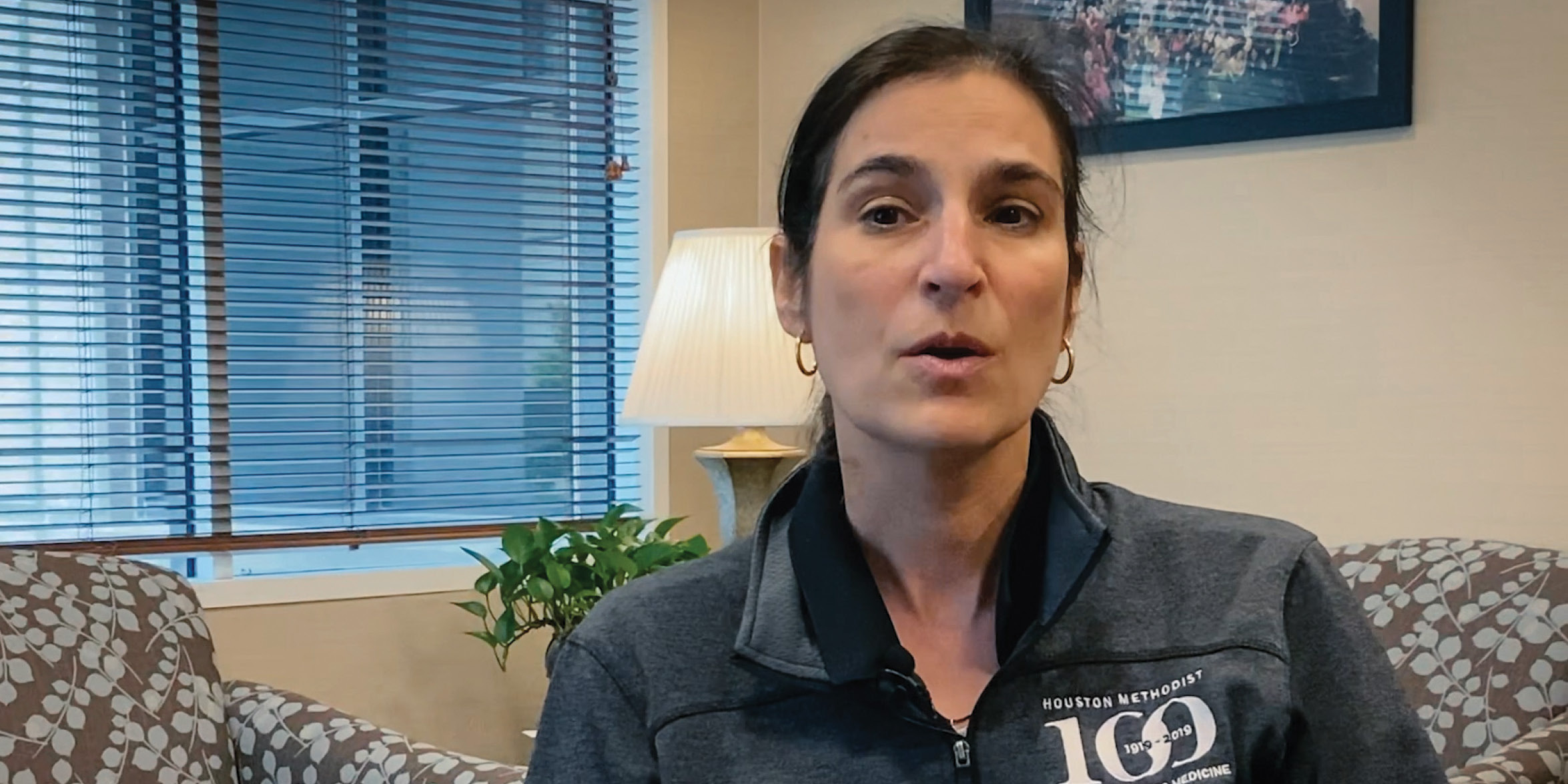

“We can have doctors in New York taking care of patients at night via telemedicine,” says Roberta Schwartz, PhD, MHS ’94, executive vice president and chief innovation officer at Houston Methodist, a system of seven hospitals in Greater Houston. “This is also how families are able to visit ventilated patients.”

Schwartz’s technology innovation team had been working on rolling out the virtual ICU for months, with the first unit set to open in March. The technology of the virtual ICU converts clinical patient data into algorithms that identify which patients most need attention and enables the hospital’s intensive care doctors to respond quickly, whether there’s an ongoing pandemic or not.

When COVID-19 hit Texas, physicians who’d had difficulty accepting the new technology were suddenly all in. Now, wired cameras are in use in 130 rooms, and hundreds of tablets allow virtual care in other units.

To provide protection for staff performing in-person procedures, Houston Methodist’s machine shop built the plexiglass boxes, as well as special intubation boxes that improve upon models created in Wuhan, China. The boxes go over patients’ heads as they lie in bed, allowing medical staff to safely intubate, free from exposure to aerosolized particles that could contain coronavirus.

“As an academic medical center, we’ve got the inhouse talent and wherewithal to build this out ourselves quickly, and we’re sharing these plans with other hospitals,” Schwartz says.

First-Responder Couple

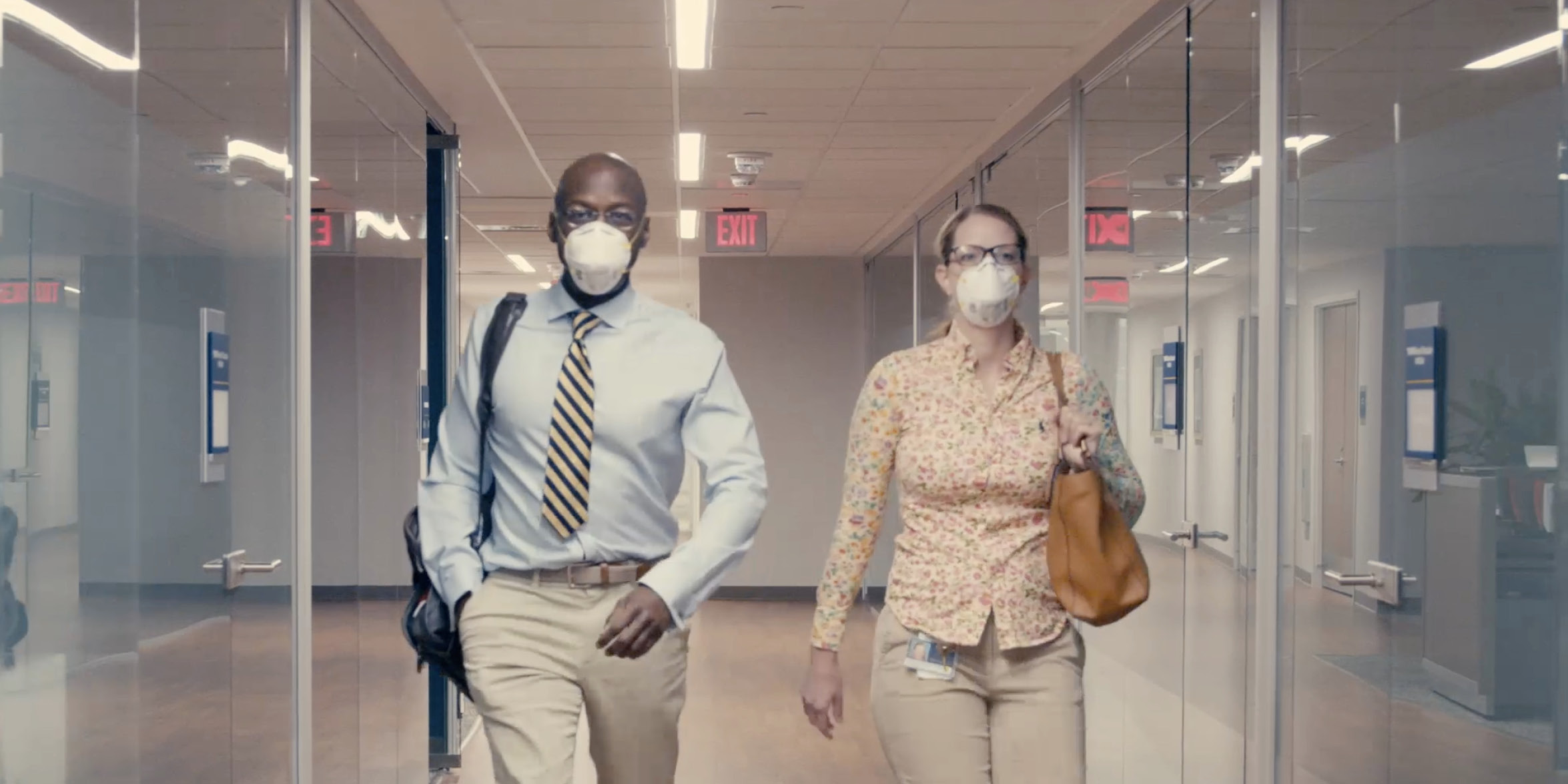

While many medical professionals have felt isolated from their families while serving on the pandemic’s frontlines, husband and wife physicians Heather Hayanga, MD, MPH ’08, and Jeremiah “Awori” Hayanga, MD, MPH ’08, have been in the fight together.

As a member of West Virginia University’s COVID-19 incident command team, cardiac anesthesiologist Heather Hayanga led development of systemwide protocols for safely caring for surgery patients at WVU hospitals. One example: Ensuring that anesthesiologists intubate patients in a negative pressure room, which traps dangerous particles and keeps them from getting into the rest of the hospital.

Meanwhile, thoracic surgeon Awori Hayanga, also of West Virginia University, advised incident command on protocols for conducting extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, on COVID-19 patients whose heart and lungs are not working. (With ECMO, surgeons drain the patient’s blood, pump oxygen into it, and return it to the patient’s body.)

Because of his ECMO expertise and his work studying the use of artificial intelligence to prevent outbreaks, in April Awori Hayanga was appointed special adviser to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

All of this with a 3-year-old at home.

“We’ve just gone with the flow and we’ve done what we needed to do to get the job done,” Heather Hayanga says.

Communicator and Adviser

When other people were stocking up on shelf-stable food, medication, and toilet paper ahead of COVID-19 lockdowns, Josh Sharfstein, MD, bought a microphone.

With that simple tool and some help, the Bloomberg School’s vice dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement launched the podcast Public Health On Call. It offers listeners daily coronavirus insights from experts in fields ranging from epidemiology and medicine to history and business.

From its first episode on global preparedness, misinformation and community transmission in early March, the podcast has been downloaded more than a million times.

Since the start of the pandemic, Sharfstein has stepped—or rather sat—in front of the camera many times, too, appearing on MSNBC, PBS, C-SPAN, and others from his basement office. And every Thursday, he shares information with mayors across the nation in a weekly briefing co-hosted with Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Harvard Kennedy School, and Harvard Business School.

“I want to be of direct assistance to health officials, governors, mayors who are reaching out,” he says. “But I also want to bring the strength of the School to all of those people and their organizations. So, I'm constantly linking faculty [to officials], trying to identify ways to bring the research that the School does to the point of action.”

From Civil War to COVID-19

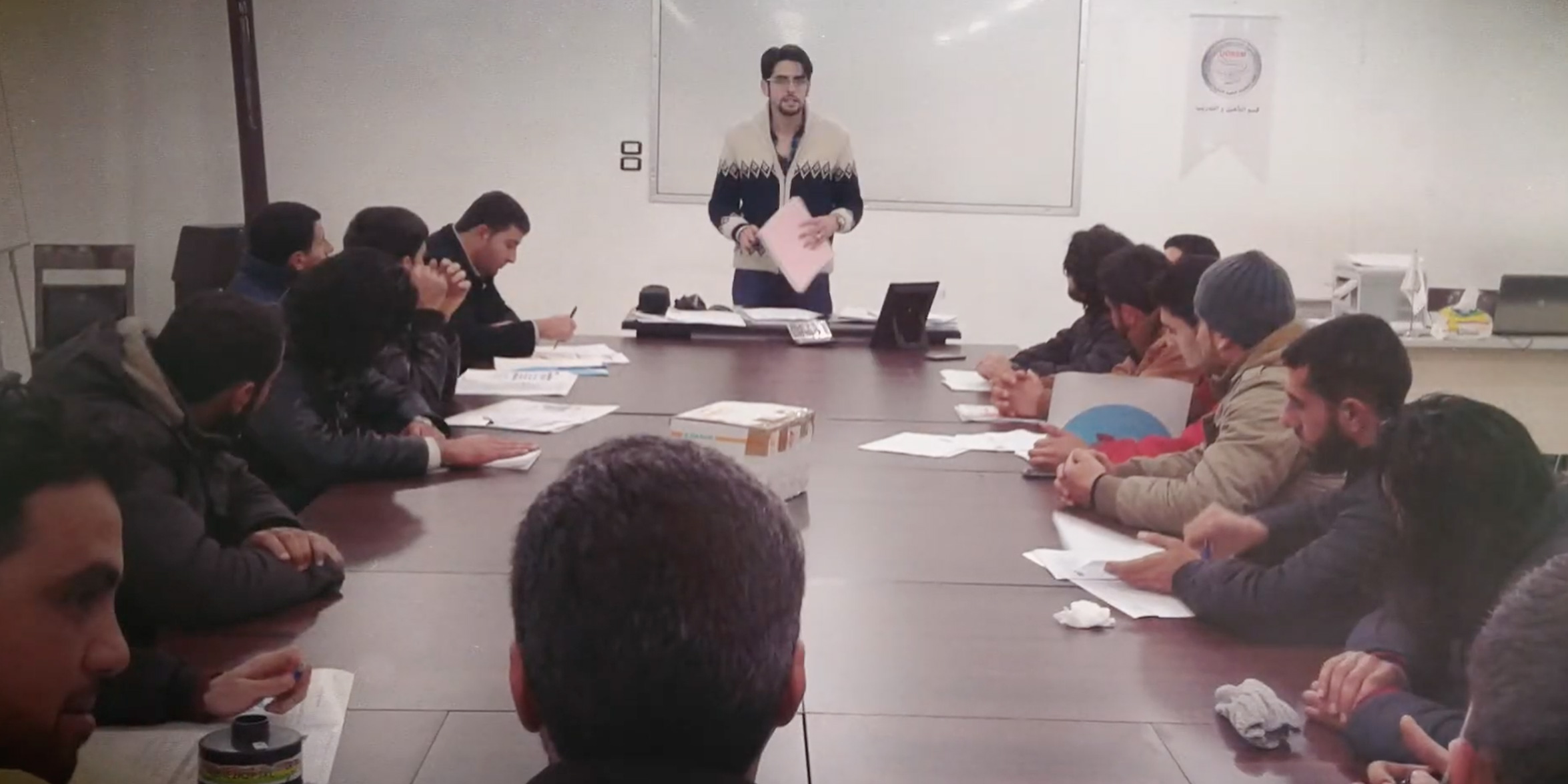

As a medical student in his native Syria, Houssam Alnahhas put his education on hold in 2011 to lead an underground medical team in Aleppo treating injured demonstrators at the start of the country’s civil war.

The Bloomberg School MPH student now finds himself in the midst of another crisis—the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although he does not have the required certifications to practice medicine in the U.S., he’s volunteering on the ground helping front-line medical staff at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center do their jobs.

As deputy area commander, he supports emergency department leadership in the COVID-19 response, mainly by helping to coordinate operations in the surge tent, a temporary structure near the hospital entrance to screen and test people with COVID-19 symptoms who are not critically ill. The idea is to shield emergency department patients from possible exposure.

Alnahhas ensures that the tent is stocked with needed medical devices and PPE and that protocols are in place to maintain a safe environment.

Safety was nowhere to be found in Aleppo when Alnahhas risked his life to deliver medical care to protestors. As the conflict escalated, three of his colleagues were detained, tortured, and killed.

Ultimately, working in a war zone led him to public health. “In an active conflict, it’s not enough to react to what’s happening,” he says “It’s a necessity to plan ahead to deploy a response.”

While the Syrian civil war and the COVID-19 pandemic are starkly different crises, Alnahhas sees a clear parallel.

“What the world is witnessing right now with the COVID-19 pandemic and what I experienced back in Syria is the uncertainty. When people don’t know exactly what will happen next, they don’t have enough evidence to build any response, to build any policy,” Alnahhas observes. “In these events the role of public health is clear … in both developing and developed countries.”

Navajo Nation’s COVID-19 Fight

They call it Dikos Ntsaaígíí-19.

It means “the big cough that is called 19” in Diné Bizaad, the language of the Navajo people.

The Navajo Nation, in the southwestern U.S., has been hit hard by COVID-19, with 5,661 cases by early June. That translates into the highest known rate of infection in the country.

Systemic barriers like lack of running water, crowded living conditions, poor indoor air quality, widespread poverty, and pervasive chronic diseases are to blame, says Laura Hammitt, MD, an associate professor in International Health who directs infectious disease programs at the Bloomberg School’s Center for American Indian Health.

The Navajo Nation is working with the Center and others to expand testing and roll out a contact tracing program that will employ many tribal members who can’t do their regular jobs during the pandemic.

But people who test positive can’t wash their hands without water, multigenerational households can’t quarantine without sending someone to get the groceries, and individuals can’t isolate themselves without a safe place to go, Hammitt says. So, the Nation and its partners—including the Center—support those who are infected, and their families, by providing clean water and handwashing stations, distributing food and cleaning supplies, and providing shelter for isolation and quarantine. Contributors to the effort include the U.S. Indian Health Service, FEMA, and relief groups like actor Sean Penn’s CORE and chef José Andrés’ World Central Kitchen.

Could this wholesale emergency response lead to long-term solutions for problems that predate the coronavirus?

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” Hammitt says.

An Ebola Expert Tackles COVID-19

In his native Liberia, just two years after earning his MPH at the Bloomberg School, Tolbert Nyenswah led the public health response to the 2014 Ebola epidemic, steering an out-of-control outbreak to containment.

Now, as a senior research associate in International Health, Nyenswah is drawing on some lessons from the Ebola crisis in the global battle to tame COVID-19.

He’s consulting with African health officials about coordinating elements of crisis response based on the model he built in Liberia. And he helped to develop the Bloomberg School’s free online contact tracing course with Bloomberg Philanthropies. The project aims to help train a workforce of contact tracers to identify confirmed COVID-19 cases, trace their contacts, and isolate positive cases.

Nyenswah, who has a law degree, contributed to the portion of the curriculum focused on ethical and legal issues around contact tracing, isolation, and quarantine.

“Contact tracing helped end the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and it can help end COVID-19,” he says.

As the world impatiently awaits a solution to contain the pandemic, Nyenswah says a key lesson that has emerged since the world learned about the novel coronavirus in early January is the necessity of “dealing with an outbreak at its source.”

“The world is interconnected,” he says. “What happens in a village in a low- or middle-income country can affect a city like New York and other parts of the world.”

Making Contact

Infectious disease epidemiologist Emily Gurley, PhD ’12, MPH, still remembers when most people couldn’t tell you what an epidemiologist did.

That was before public health experts became in-demand media sources, sought out on a daily basis to make sense of the coronavirus pandemic for the general public.

As lead developer of the Bloomberg School’s free online COVID-19 Contact Tracing course, Gurley has become a go-to expert on contact tracing, an old-school public health tool to slow disease spread by identifying positive cases and their contacts and asking them to quarantine.

“Contact tracing is one of the best tools we have right now until we get a vaccine or other type of intervention to stop the spread,” says Gurley, an associate scientist in Epidemiology.

The course aims to help train a sufficient national workforce of COVID-19 contact tracers, estimated at 100,000 by the Bloomberg School’s Center for Health Security. Enrollments have surpassed 500,000 since the course launched on May 11.

Gurley attributes the course’s success to the fact that it’s actually much more than a course.

“For public health departments, I think it’s serving the purpose of giving them a leg up and building the contact tracing teams that they need to stop transmission in their communities,” she says.

The course covers the basics of COVID-19 transmission, the contact tracing process, which involves identifying positive cases of COVID-19 and their contacts and asking them to quarantine to slow disease transmission in the community. Ethical considerations and effective communication are also covered.

“Ultimately contact tracers are disease detectives, therapists, and social workers,” says Gurley. “They need to, of course, understand the disease and how contact tracing works. But even more than that, they have to be good at talking to people, to be a good listener and making connections with people.”

Following the Data

Between March 11—the day the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic—and May 2, New York City saw over 24,000 more deaths than normal for that time period.

Most of those deaths were confirmed or probable COVID-19 cases. But more than 1 in 5 were not immediately known to be related to the virus that causes COVID-19.

Jaimie Shaff, a Doctor of Public Health student in the Health, Equity, and Social Justice track at the Bloomberg School, leads a team of data scientists who are crunching the numbers for the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Using data from New York City surveys, the Census Bureau, death reports, location services from phones and other devices, and other sources, they have helped the city shift its thinking on how to battle the pandemic.

In addition to focusing on individual COVID-19 patients, the health department is now zeroing in on neighborhoods and communities most hard hit by death and illness during this unprecedented public health emergency.

That’s the best way, Shaff says, to keep people safe not just from the new coronavirus but also from other, invisible epidemics worsened by isolation and stress, like domestic violence, mental health crises, and heart disease.

“There are so many aspects to this pandemic we need to look at as we think through how we’re going to respond to an uptick in the future,” she says.

An Old Treatment is New Again

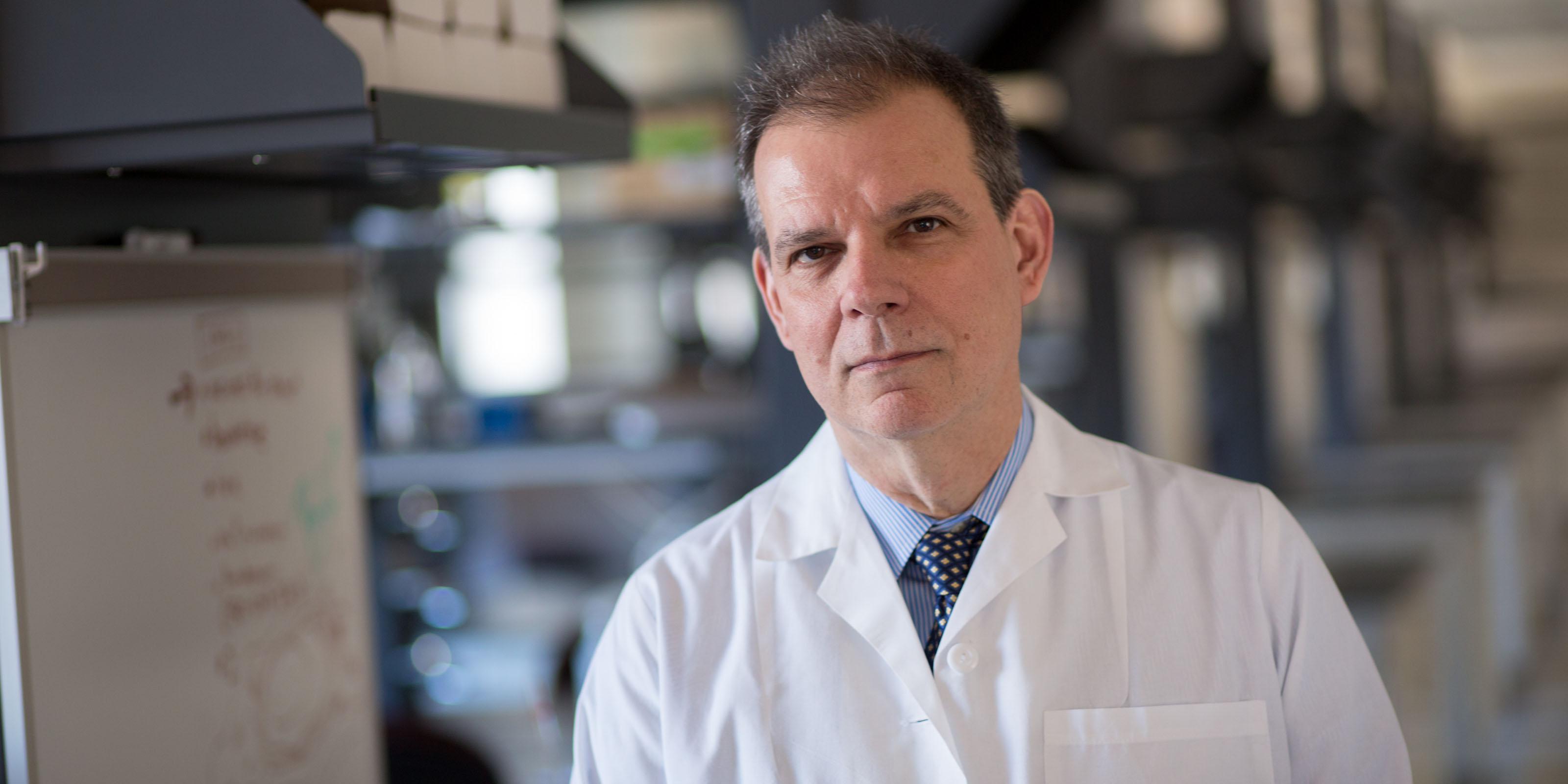

On March 1, ten days before the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, Arturo Casadevall, MD, PhD, MS, chair Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Bloomberg School, already had a plan of attack: resurrect a 130-year-old therapy to go up against the novel coronavirus.

His late-February Wall Street Journal op-ed proposed the use of convalescent plasma therapy to treat and prevent COVID-19. The technique would transfer COVID-19 antibodies–in the form of plasma from the blood of recovered patients—to people with active disease to trigger an immune response.

Soon enough, a convalescent plasma initiative took off. Infectious disease experts across the U.S. got on board, hospitals signed up, and regulatory agencies fast-tracked approvals of the experimental therapy.

By late March, COVID-19 patients in the U.S. had received plasma therapy, and in less than three months the treatment had been given to 20,000 hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

“Usually doing something like this would have taken many months to years,” Casadevall says, “but everybody has a can-do attitude, and you can see how something can be done very rapidly in the middle of a calamity.”

The effort got a major funding boost early on when Bloomberg Philanthropies contributed $3 million and the state of Maryland provided $1 million to support research into convalescent plasma therapy.

Several controlled randomized trials involving hospital patients are exploring whether the therapy can speed recovery from COVID-19. And two Johns Hopkins–based trials are looking at whether plasma can ward off COVID-19 in people like health care workers who have major exposures to SARS-CoV-2, and if the therapy can prevent progression to a severe form of the disease in people who are sick at home.

“If we can keep people out of the hospital, it protects hospitals, it protects our infrastructure, but most importantly, it protects those people from getting worse,” Casadevall says. “If we can do that, we’re going to have a huge impact on the mortality of this disease.”

Evidence-Based Policymaking

In many countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered polarizing conflicts over safety measures, data accuracy, the timing of reopenings, and other aspects of the crisis.

The island nation of Taiwan managed to avoid such conflicts, and has emerged as a success story in controlling the spread of coronavirus. Guiding the response was the country’s former vice president Chen Chien-jen, who earned a Doctor of Science degree in epidemiology and human genetics from the Bloomberg School in 1982. Chen credits his science education with helping him to effectively navigate the worlds of public health and politics.

“As a politician, I had to carry out evidence-based policymaking, which requires scientific vision and good training in scientific thinking,” says Chen.

His public health background served him well in keeping the coronavirus at bay: The island nation of 23 million has recorded fewer than 500 COVID-19 cases and 7 deaths.

Key elements of Taiwan’s response include early, robust disease surveillance, travel bans from parts of China, advance alerts to hospitals to prepare for COVID-19 patients with strengthened infection control and adequate personal protection equipment, and daily news conferences by Taiwan’s CDC to provide the public with updates on the pandemic.

“Through this transparency and openness we gained the public’s trust, which increased compliance with government regulations and guidance,” Chen says.

In May, Chen resigned as his country’s vice president to return to Academia Sinica, a research institution in Taiwan where he previously held the position of vice president. As a distinguished professor there, he is leading efforts to develop coronavirus rapid testing kits and a COVID-19 vaccine.

Measuring COVID-19’s Mental Health Impact

In the early days and weeks of the pandemic, "flattening the curve” became a common goal. To prevent spikes in infections and hospital admissions, states issued stay-at-home orders. People settled in for long stretches with family, or alone.

Elizabeth Stuart and a group of faculty and students at the Bloomberg School quickly recognized that the pandemic and infection prevention efforts could also have significant mental health consequences. So, over one weekend in mid-March, the group developed key questions to add to existing national surveys to measure rates of anxiety and depression.

“We wanted to make sure that the mental health implications were also going to be examined,” says Stuart, a professor in Mental Health and associate dean for Education at the School.

Since then, the COVID-19 Mental Health Measurement Working Group has partnered with the Pew Research Center, other universities, and even Facebook to add mental health measures to their coronavirus-related surveys. About a million people per week have filled out the Facebook surveys.

One surprising finding so far: People ages 18–24 are showing much higher levels of distress than older adults—the opposite of what researchers expected, Stuart says.

Such data can help local decision makers effectively allocate resources for prevention and treatment strategies. The findings could reveal where additional mental health providers are needed and inform communication campaigns that connect people with services, says Stuart.

More data-driven responses to mental health needs could be one of the pandemic’s lasting impacts.

“I think that the current pandemic is really showing the country and the world that mental health is a key part of health,” Stuart says.