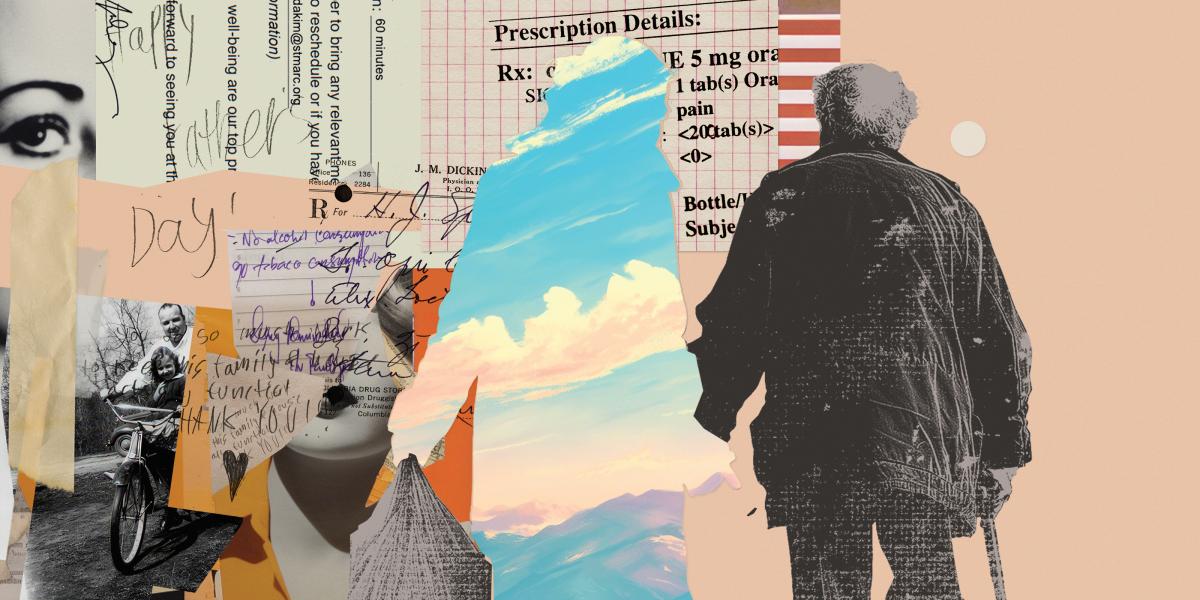

Caregivers: Health Care’s Hidden Workforce

Caregivers are the glue in a fragmented system of health care and support services for a ballooning population of aging Americans.

“A lot of my life is taking my dad to doctors’ appointments,” says Mia Fantaci Hale, 34. When her father’s health is poor, she might take him to three different doctors’ appointments in a day. Sometimes being his unpaid caregiver means changing bandages and administering IV medications through PICC lines. Sometimes it means checking his mail to make sure his Medicaid isn’t getting cut off. Always it means hours spent on paperwork, phone calls, and patient portals to manage his needs and communicate with providers and insurers.

“Caregiving is pretty much my whole day, between my 2-year-old and my dad,” Fantaci Hale says—and she’s expecting another baby in May.

Caregivers are an increasingly important part of the aging discussion, especially as older people are living in their communities longer. They help with health care delivery and decisions, but often their work goes unseen and unacknowledged. Jennifer Wolff, professor in Health Policy and Management and director of the Roger and Flo Lipitz Center to Advance Policy in Aging and Disability, often calls them “care partners,” reflecting their important role as members of the care team.

There are already about 26 million unpaid caregivers of older adults in the U.S., and about 4.8 million paid direct care workers like home and residential aides. By 2060, 94.7 million Americans—nearly a quarter of the U.S. population—will be 65 and older, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The growing need for caregivers is slowly gaining national attention, but not as quickly as it should, say experts like Katherine Miller, an assistant professor in Health Policy and Management. “When we think about the public health investments that have occurred for other issues the CDC has declared an issue, caregiving has not been elevated in the same way until recently,” says Miller, PhD, MSPH.

The CDC declared caregiving an “important public health issue” in a 2018 report detailing the prevalence of unpaid caregiving and the health issues facing caregivers, including stress, lack of sleep, and high rates of chronic illness. The first-ever national strategy to support family caregivers was launched in 2022. In May 2023, President Biden signed an executive order to improve access to care and support for caregivers, including better compensation and benefits, insurance, and mental health care. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released a report on April 11 on how best to support family caregivers in the STEM workforce, including recommendations for comprehensive federal paid leave.

“It’s very exciting. Even though it has been slow, the pace seems to be accelerating,” says Wolff, PhD ’03, MHS ’95.

Fantaci Hale and her younger sister were teenagers when they began caring for their father around 2005. Their parents had divorced, and his primary struggle was ADHD. His physical health seemed good—he loved cooking, biking, Rollerblading, and running. But then, around 2016, his health began deteriorating in a cascade of symptoms and diagnoses: heart failure, diabetes, dizziness, fatigue, gastrointestinal issues, and others.

Fantaci Hale grew up hearing that in her father’s Italian American and her mother’s Trinidadian cultures, children take care of their elders at home, so there was “a tremendous amount of pressure” to become her father’s primary caregiver, she says. But finances also played a role: “There was never an option on the table for something like assisted living, because financially it just doesn’t make sense.”

So, when Fantaci Hale and her husband decided to leave Georgia in 2019, they made choices with her father in mind. They moved to Massachusetts in part for its social safety net and found a home with an in-law suite for the day her dad would need to move in. That day came quickly, in early 2020.

She’s glad her father can be an important part of her family’s life. She only wishes she were facing the challenges with more support—more resources, respite, respect. “It’s really overwhelming sometimes,” she says. “It really truly feels like you have zero time to yourself.”

Jeromie Ballreich, PhD ’17, MHS ’12, an associate research professor in HPM who lives with quadriplegia, has had dozens of paid caregivers over the past two decades, and his family also helps with care. “They’re critically important in the health care system,” he says.

Yet medical professionals “rarely integrate the caregiver as part of the whole medical process,” he says. Sometimes it’s appropriate for patients to have visits with a provider one-on-one, but other times, it’s a puzzling omission. “I’ve experienced many times when the caregivers are not involved, and that’s a problem because they are the ones doing a lot of the frontline medical tasks daily,” he said. “The fact is, I’m not the one doing the bandage dressing daily—that’s the caregiver.” Integrating caregivers into medical care can also improve that care. “It needs to be a bigger part of our national conversation for health care,” Ballreich says.

Chanee Fabius, PhD, an HPM assistant professor, agrees. “One of the biggest issues is the lack of coordination that we see between medical care, long-term services and supports, and family caregivers, and it’s usually the family caregiver that’s tying all the knots together and making all the pieces fit together,” she says. “If we could improve care coordination and communication between systems, it probably would take some of the burden off of family caregivers.”

Patient web portals are one potential tool for this coordination. The current system is strongly focused on patient autonomy and patient privacy, without acknowledging that many people rely on others to navigate the system, Wolff says. With other members of the Coalition for Care Partners, Wolff is working to improve portal systems in several ways, including by creating roles for caregivers so that providers know who they are, what they’re doing, and what research, resources, and referrals they need. “It benefits the integrity of the information, but it also gives care partners legitimacy,” Wolff says. Excluding them from patient portals “perpetuates this idea of invisibility, that the caregiver doesn’t have a role.”

Defining her role with doctors—and with her father—is one of Fantaci Hale’s biggest struggles. “It is a … fine line between what he is comfortable with me saying to them and what is actually happening at home,” Fantaci Hale says. “A lot of the time when we go to doctors’ appointments and I put my foot down and I say, ‘Hang on, you’re masking how bad this issue actually is,’ he gets really upset with me,” she says. She would like to have a few minutes occasionally to consult with clinicians alone, while also respecting her father’s independence and autonomy. “It’s really hard as our parents get older, because there’s a lot of pride involved,” she says.

The economic value of care provided by unpaid caregivers like Fantaci Hale far exceeds that paid out-of-pocket or by public and private insurers.

Although Fantaci Hale’s father receives Medicaid, applying for caregiving funds from Medicaid “feels very daunting,” she says, adding that it would be an enormous help if social workers could go through the paperwork with her family. “It really feels like there’s an extraordinary amount of hoops to jump through if you want to establish care for a loved one,” Fantaci Hale says. Meanwhile, she and her husband, like many family caregivers, spend their own money on expenses related to providing care.

Most paid caregiving—including for direct care workers, nursing home aides, and some family caregivers—is funded through Medicaid, which has significant asset limits determined by states. More than 6.9 million seniors received Medicaid in 2019, which is only about 10% of Americans over 65. Medicare does not pay for long-term services and supports, regardless of who provides them.

Fantaci Hale is grateful for the community support she’s found at Tandem, a co-working community with onsite childcare she is helping to create in Salem. “Anyone who is doing any sort of caregiving in any capacity really needs that community because it can be mentally and emotionally draining to be filling somebody else’s cup constantly,” Fantaci Hale says.

At Tandem, she connects with other intergenerational families and finds tremendous comfort in “being able to talk to somebody else about how stressful sometimes it can be having a grandparent or grandparents in the house.” Just as important, she enjoys sharing the good parts—the French onion soup her dad made from scratch for Easter, the hours he spends with his granddaughter in the garden—and the reminders that this time together is worth the challenges.

“One day, my dad won’t be around anymore,” Fantaci Hale says. “I want to know I did the best I could for him when that day comes.”