Sudden Impact: When Health Programs End

What happened when stop-work orders shut down four USAID projects?

Some emails arrived out of the blue. Others came after weeks of dread. Either way, they carried program-ending certainty. Earlier this year, more than 6,000 USAID grants were terminated as the agency was rapidly dismantled in Washington, D.C. While the ultimate effects of the withdrawal of U.S. support may never be measured, the following four reports, originally published by Global Health NOW, uncover the consequences of USAID programs ended in South Africa, Nigeria, India, and Peru.

HIV Untamed in South Africa

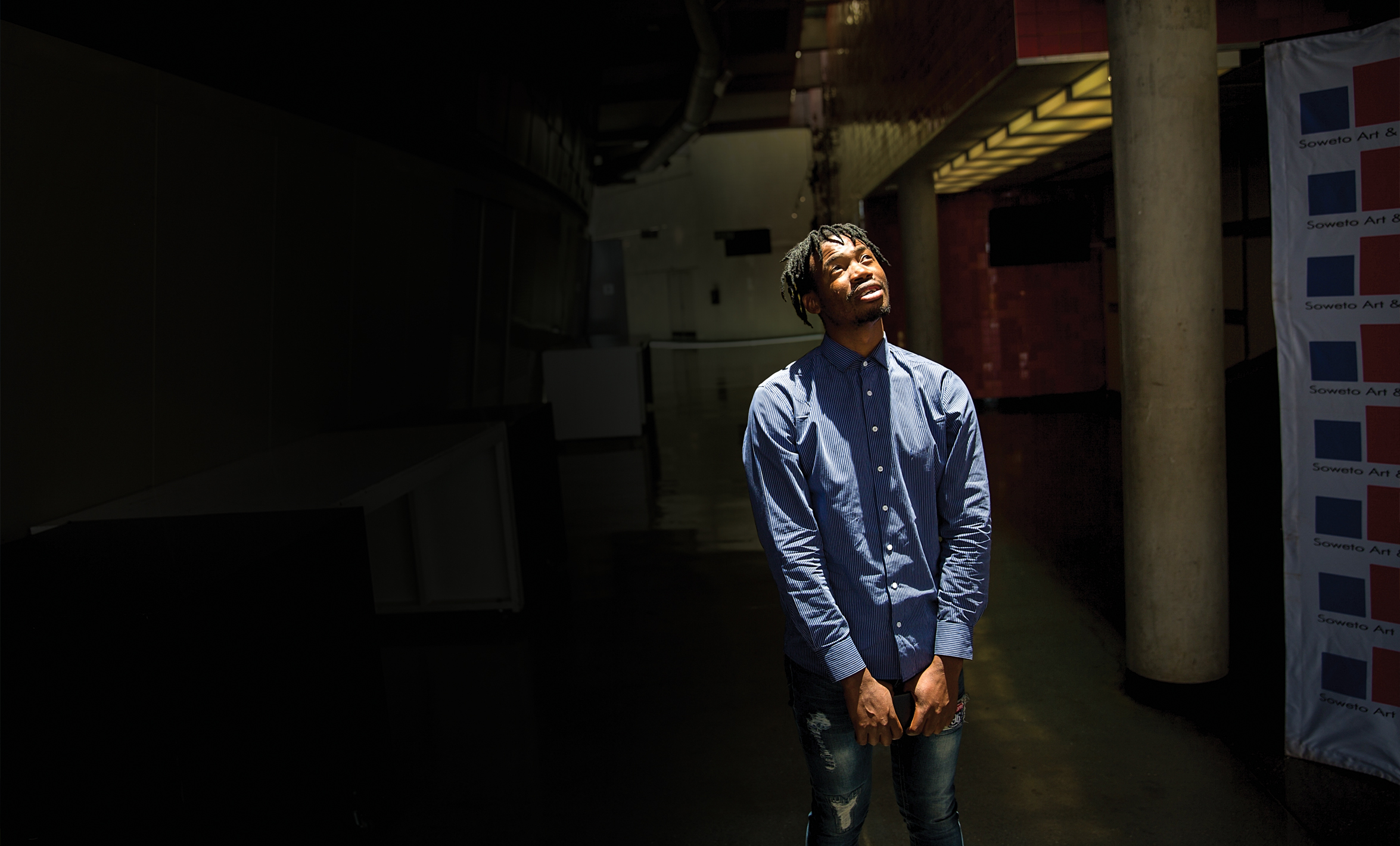

By Elna Schütz

All the groundwork had been laid and the official approvals for a Phase 1 clinical trial were secured. But now, vials of vaccine sit untouched in laboratory refrigerators.

U.S. government research funding cuts halted the mRNA HIV vaccine study, part of the BRILLIANT consortium, mere days before its planned start in March 2025.

Such a vaccine could fundamentally change the HIV burden for South Africa, which reports the world’s highest number of people living with HIV—7,700,000 in 2023.

Just six months ago, there was optimism around controlling the HIV epidemic, says Linda-Gail Bekker, the trial’s lead and director of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre at the University of Cape Town. “We were really in a position where we could maybe tame the tiger and put it back in its cage,” she says.

Now, she says it feels like the cage’s doors have been opened wide and the key thrown away.

The U.S. administration’s executive order to cut all aid funding to South Africa has disrupted prevention and care—and will likely lead to thousands of deaths. South Africa faces a double-whammy, with both researchers and people on treatment feeling the impact. As of May, the cuts also include NIH grants and subgrants, meaning South Africa cannot even receive parts of grants run mainly in America. This will be an estimated annual loss of $350 million in funding to South Africa, according to Bhekisisa.

“We can say that it is a devastating domino effect that goes on daily, with repercussions far beyond what we imagined,” says Thesla Palanee-Phillips, director of clinical trials at Johannesburg’s Wits RHI research institute.

The U.S. cuts are particularly devastating because South Africa is the world’s third-largest producer of HIV research publications. It has also made significant contributions to globally used HIV innovations, like the long-acting prevention injectable lenacapavir, and to HIV cure research. The cuts also tear apart the research infrastructure and long-established relationships with funders that Bekker describes as a well-oiled system. “People need to understand the incredible loss of future dividends from the investment that has already been made,” she says. “And—to be entirely transactional—this just does not make good business.”

Given the current uncertainty, HIV researchers are trying to find new funding and to become less reliant on a single source.

Bekker moved some researchers in her organization to other work to shield them from layoffs. She is hesitant to turn to the government for research funding when the need for clinical lifesaving treatment, the top priority, is so great, and says they might need to explore whether some of the research could run parallel to clinical efforts.

Until future funding becomes clearer, many participants have been shut out of clinical trials, and researchers worry about what might happen next.

“It takes us decades to build momentum and be a recognized scientist,” Palanee-Phillips says, “and overnight decisions are being made to just destroy careers and the work that we’ve done.”

Read the unabridged version of this article at Global Heath NOW.

Lost Momentum in Nigeria’s Malaria Fight

By Paul Adepoju

At the Alegongo Primary Health Centre clinic in Ibadan, Nigeria, a nurse greets Ibidun Arike warmly before administering a rapid malaria test to her feverish son, Olu, 5. Within minutes, the test confirms malaria, and the nurse dispenses free antimalarial medication along with instructions to finish the entire dose.

“It’s malaria again,” Arike sighs softly. As a trader who sells groceries to support her family, she is relieved and grateful for Alegongo’s free malaria services.

Amid broader uncertainties surrounding the withdrawal of U.S. funding for anti-malaria programs in Africa, Arike’s sense of security could soon unravel.

Nigeria bears the highest malaria burden, with 26% of global cases (over 260 million total) and over 30% of malaria-related deaths (nearly 600,000) in 2023, per the 2024 World Malaria Report. However, as part of the High Burden to High Impact (HBHI) initiative, Nigeria has seen a 13% reduction in mortality rates since 2017. Prevalence fell from 42% in 2010 to 22% in 2021, while a steady flow of donor‑funded supplies meant that Nigerians like Arike could walk into primary health centers and receive free rapid tests and artemisinin‑based combination therapy malaria medications .

Efforts by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (CCP) helped make that progress possible. CCP staff trained health workers, supervised the distribution of antimalarials, and ensured that local health centers maintained best practices in malaria case management.

Now, much of that work has stopped with the U.S. government’s sudden cessation of funding for malaria initiatives earlier this year.

“Everyone was let go. … We thought there might be a new project, something to transition into. But now, there’s nothing,” says Ade*, who worked on malaria control efforts with CCP in Abuja for more than seven years.

For now, Alegongo and other frontline clinics still have reserves of tests and antimalarials. But “these stocks won’t last forever,” Ade notes, warning, “What people don’t see now are the logistical strings being cut. … Those supply chains, once broken, don’t repair easily.”

Without new funding, insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) could languish at ports. The steady supply of antimalarials could run dry. And the surveys that anchor accountability by tracking diagnostics, ITN ownership, prevalence, etc., would vanish. It’s an obliteration of both the gains and the very ability to see them.

The abrupt loss of supportive oversight also means that newly recruited or transferred health workers may soon lack the training required to accurately diagnose malaria. (It’s an important skill: Fevers are frequently misdiagnosed as malaria.) Without that training, Ade expects more diagnostic mistakes—draining precious drug supplies, obscuring health data, and risking progress against the disease.

For Ade, the real impact isn’t just in the lost job, but in the lost momentum toward eliminating malaria. “When the partners leave, accountability diminishes. … Without measurement, without external pressure, it’s the ordinary Nigerian—the pregnant mother, the young child—who ultimately pays the price,” Ade says.

*Ade’s name has been changed to protect their identity.

Read the unabridged version of this article at Global Health NOW.

India’s TB Battle Just Got Harder

By Cheena Kapoor

Mohammad Arif, a 45-year-old rickshaw puller, dropped out of tuberculosis treatment for several months because he couldn’t afford to miss work to visit the clinic.

Then his cough worsened, so he returned to Lok Nayak TB and Chest Clinic, the capital’s primary government-run TB clinic. But Arif, who cannot read or write, couldn’t fill out a form required to enter the clinic.

Feeling lost after waiting for a few hours, he left for home.

Arif isn’t the only patient challenged by the arduous standard treatment for TB, which requires daily medications and monthly clinic visits.

“The doctors in these hospitals cater to hundreds of patients a day and have minimal time for explanations or comprehensive care, focusing primarily on eliminating the bacteria rather than supporting patients holistically, which leads to many patients dropping out of the program,” says Akshata Acharya, a recent MDR-TB survivor and author of Eclipsed, a book about her journey overcoming tuberculosis. “This is where NGOs have played a significant role in ensuring the patients continue their treatment.”

One of those NGOs—the Karnataka Health Promotion Trust—supported a “TB buddy” system of guides who help TB patients with documentation, offer emotional support, and ensure treatment completion. The project focused on vulnerable populations, including those with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI)—individuals infected with TB bacteria but who do not have the disease. While precise data are unavailable, the WHO estimated in a 2023 TB report that approximately 360,000 children under 5 in India were eligible for LTBI treatment, with 5%–10% at risk of developing active TB (when people feel ill and can spread TB germs to others). Continuing support for the TB buddy project ended with USAID cuts.

Although the country has the highest TB burden in the world and accounts for 26% of all TB cases, India’s Health Minister Jagat Prakash Nadda recently said he expects India will eliminate TB by the end of this year. Few experts believe India will reach that target this year—or anytime soon—given that the disease causes at least 2.8 million new cases and 325,000 deaths each year.

The USAID funding cuts to prevention programs will impact the country’s elimination goals. For example, USAID has contributed more than $140 million to the government-run TB Mukt Bharat (TB Free India) program, which sought to prevent TB transmission. Also canceled is USAID’s support for the Tuberculosis Health Action Learning Initiative, which led TB awareness activities and supported vulnerable populations, such as the urban poor, tribal communities, migrants, and industrial workers.

Despite the USAID cuts, the country is still ramping up its efforts against TB, says Sanjay Rajpal, MD, medical director of the New Delhi Tuberculosis Centre. “We’ve felt the pressure from higher-ups to do our best in reducing the numbers,” said Rajpal. “COVID has set us back, so we need an additional two to three years, but we’re confident we’ll reach our goal before the WHO’s [2030] global target.”

Read the unabridged version of this article at Global Health NOW.

Peru’s Illegal Mining Surges … and Destroys

By Lucien Chauvin

Soaring gold prices and plunging U.S. government funds are pushing Peru’s southeastern jungle into a public health crisis.

A gold rush in the area has pushed illegal gold exports from Peru to $6.8 billion in 2024, surging 41% over 2023. It is drawing workers and large amounts of mercury, which is used to extract gold from sediment. The result has destroyed forests and poisoned the environment, says Juan Pablo Murillo, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

The population surge and unsanitary conditions in makeshift mining camps have also led to an increase in diseases like leishmaniasis, leptospirosis, and tuberculosis in Peru’s Madre de Dios department, which borders Bolivia and Brazil.

The use of mercury has become a major threat because it is being dumped in watersheds. More than half the population in Puerto Maldonado, the department’s capital, has blood mercury levels that are double the WHO reference limit. The heavy metal can cause impaired speech, hearing, and walking; memory loss; and tremors.

With the demise of USAID, the U.S. ended efforts to limit illegal mining and its impacts on the environment and human health in Madre de Dios, says Luis Fernández, PhD, executive director of Wake Forest University’s Center for Amazonian Scientific Innovation. Projects had reforested devastated areas and traced how mercury poisoned humans. They also encouraged residents to reduce the consumption of fish with the highest mercury levels—usually larger fish higher in the food chain—and tried to persuade miners to use techniques that do not require mercury. But that approach is more time-consuming and expensive.

U.S. support for this work ended in January. “The entire sector working on illegal gold mining and its causes has been affected,” says Fernández. “And with the price of gold above $3,000 an ounce—it is basically like throwing gasoline on an already hot fire.”

Eusebio Ríos, a leader of the Harakmbut Indigenous people, says communities know that fish have high levels of mercury, but fish make up the protein foundation of Indigenous diets throughout the Amazon basin.

“We need to understand much more about the impact, because it is so contaminating,” Ríos says. “It is a silent threat because you do not see it. We are consuming it without knowing it or how it will affect us in the future.”

While Peru’s government and institutions plan next steps, Fernández says the most effective strategy is for authorities to focus on policing and interdiction to prevent areas from being invaded by miners and to protect areas around Indigenous communities. The work, he says, gets harder with each dollar added to the price of an ounce of gold.

“Illegal mining is fast. It comes in, takes a place apart, and the damage is profound, leaving behind a toxic legacy,” Fernández says. “Mercury does not disappear, it goes somewhere. So, when we talk about human health, we know that it is going to continue affecting populations into the future.”

Read the unabridged version of this article at Global Health NOW.