Back Story

To solve the global refugee crisis, we first need to know ourselves.

As long as we’ve been human, we’ve been on the move.

Our ancestors first walked out of Africa some 2 million years ago. And never stopped. We journeyed across Europe and Asia, crossed the land bridge to the Americas and rode the seas to the Pacific Islands. From Table Mountain in southern Africa to the Arctic, from the Great Plains to the Kamchatka Peninsula, we’ve roved since we could walk upright.

Why? Deep in our bones (and perhaps our DNA) lurk twin, opposing compulsions: dissatisfaction and optimism. We consider the present circumstances insufficient and future opportunities limitless. Small wonder we’re such a mobile species.

I began thinking along these lines while editing Divya Mishra’s article about the young refugees who fled from war and disasters in their home countries to Europe. They’ve found bitter challenges, as Mishra, our Johns Hopkins-Pulitzer Center Global Health Reporting Fellow explains in “‘We Lived Like Prisoners’” on page 40. The boys and young men have shelter and food in Greece, yes, but little access to education, training, jobs and health care. They have even less hope.

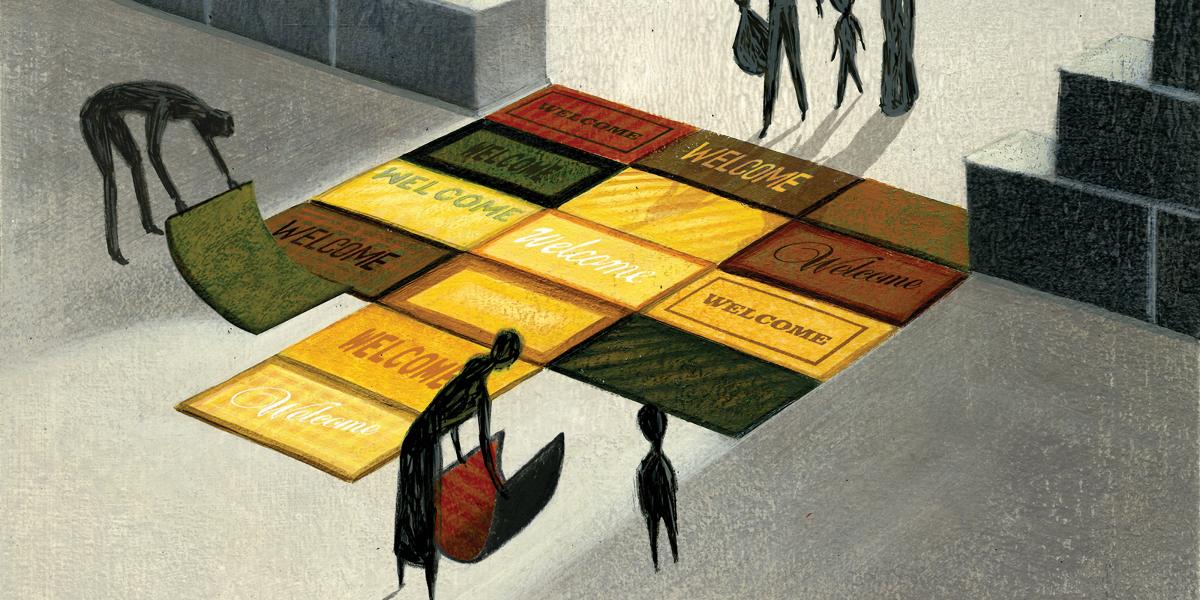

As the image on the facing page tragically attests, people leaving behind violence and poverty have found their way to the U.S. border as well. While I write this, the debate about the U.S. response rages among politicians and partisans. Anger and invective dominate the public discourse.

For the 68.5 million people forcibly displaced from their homes worldwide, we must do better. As a start, we should turn to another deep-in-the-bone human attribute: empathy.