Window of Opportunity: Addressing Teen Suicide Starts in Childhood

The prime time to teach suicide prevention may be earlier than you think.

When Holly Wilcox was growing up in Massachusetts, she became close friends with a neighbor who lived a few houses down the street. Her friend’s household was chaotic and distressing. By the time she reached her mid-teens, Wilcox’s friend had made multiple suicide attempts.

“I vividly remember how helpless I felt when she was hospitalized, like I should have done more to help her,” Wilcox remembers. “But at age 14, I did not know what to do.”

Although her friend is now a healthy adult, that experience helped shaped Wilcox’s entire career path. As an associate professor in Mental Health, she studies suicide prevention interventions for young people—teens, preteens and even younger children, populations in which suicide is becoming increasingly more common.

According to the CDC, suicide is the second-leading cause of death among youth ages 10 to 19 in the U.S. In the last two decades, suicide rates in people even younger have gradually increased: Between 1999 and 2017, they rose from 1.9 to 3.3 per 100,000 in boys ages 10 to 14. In the same age bracket for girls, rates more than tripled, rising from 0.5 to 1.7.

Untreated or undertreated clinical depression, impulsive aggressive traits, ready access to firearms, social disconnection and violence in the home or community have all been linked with youth suicide. Social media has been implicated but has not been adequately studied. The controversial and popular Netflix show 13 Reasons Why, about the suicide of a young girl, was associated with a nearly 30% jump in suicide rates among U.S. youth ages 10 to 17 in April 2017, the month after the show’s debut, according to research published April 29 in the Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

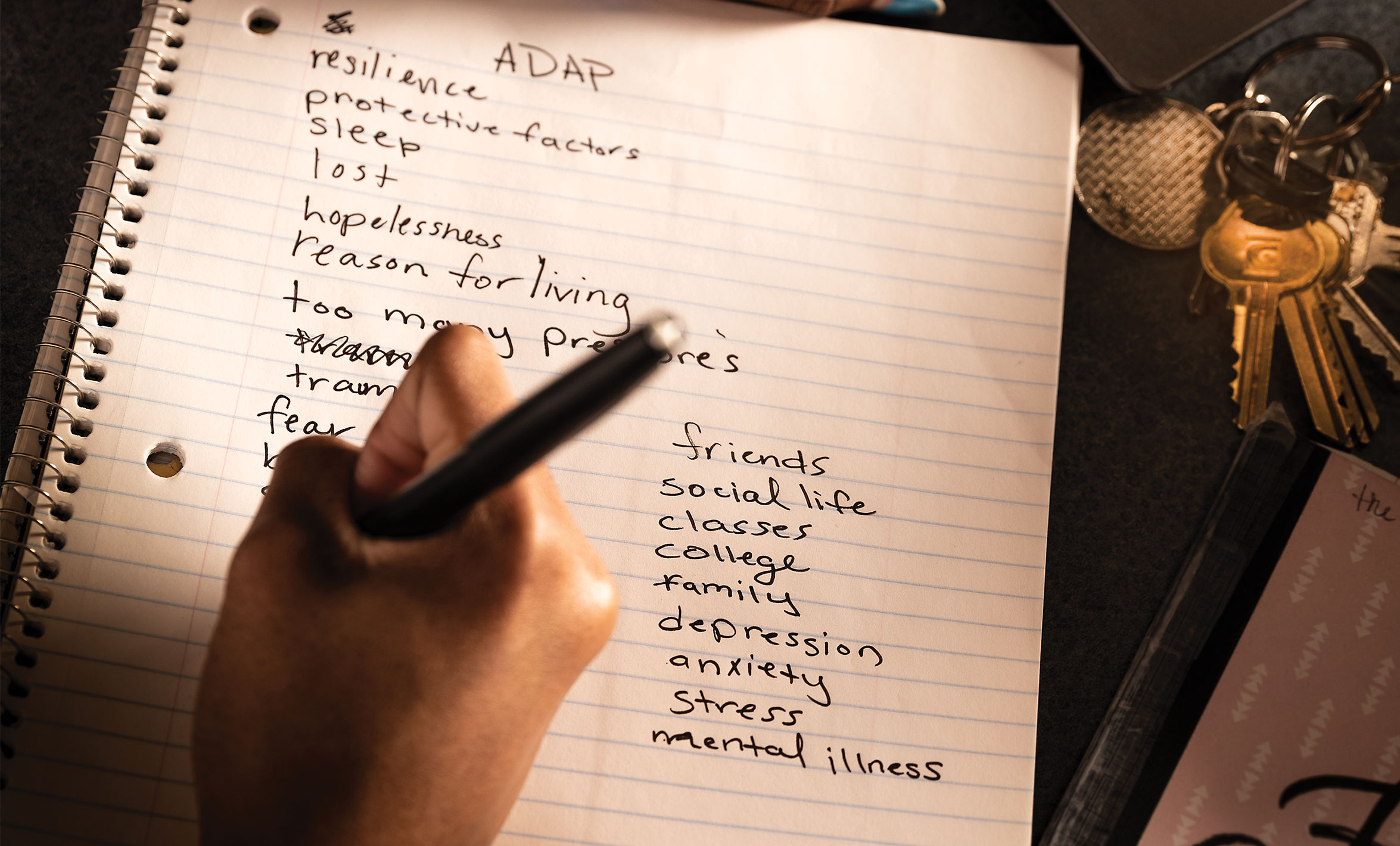

Through her collaborations with colleagues at Johns Hopkins and in the community—particularly via the Adolescent Depression Awareness Program (ADAP), started 20 years ago at the School of Medicine—Wilcox is helping to solve this public health problem, and to help young people who, like her childhood friend, struggle to find hope in their lives.

Ahead of the crisis

Wilcox, PhD ’03, MA, who has a joint appointment at the School of Medicine, always knew she wanted to work in mental health. After majoring in psychology as an undergraduate, she enrolled in a master’s program in community psychology at New York University. Before entering the program, she took a research coordinator job with David Shaffer, then director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Columbia University, who was testing the value of a suicide-risk screening program called TeenScreen in New York City public schools.

TeenScreen was a launching point for her career, Wilcox says. For four years, she performed much of the hands-on work of the program, traveling to schools in New York and beyond, administering paper screening exams to thousands of students. (Each consented to participate in the program by passive parental consent, a circumstance that would never take place today because of more stringent rules to protect study subjects, Wilcox says.)

Based on the screening results, she prioritized students for more intense assessment by mental health clinicians and helped teens at elevated risk for suicide get necessary treatment. Sometimes students were in crisis and were linked with services on the spot.

The work gave her some of her first published research aimed at better understanding this vulnerable population. When she left that position to start a doctoral program in clinical psychology at George Washington University, Wilcox was convinced that suicide prevention efforts should start at even younger ages and not exclusively focus on those individuals who are already in crisis.

“A lot of kids in the TeenScreen project said that they’d started having problems in middle school or even late elementary school,” she says. “It made me think about more upstream work, trying to target when these problems with depression and suicidal thoughts actually started.”

Wilcox chose to leave her clinical psychology doctoral program because it wasn’t quite the right fit and worked at the National Institute on Drug Abuse for the Child and Adolescent Workgroup director. In 1998, she enrolled at the Bloomberg School, where James Anthony, PhD, MSc, then a professor in Mental Health, was her PhD adviser.

Wilcox soon began working with Sheppard Kellam, MD, a professor in Mental Health who has long studied the Good Behavior Game, a decades-old strategy to improve self- and group regulation and to stimulate prosocial behavior among school-aged children. Her own research on this strategy has shown that it has significantly reduced suicidal thoughts and behaviors in two cohorts followed long-term since the 1980s, compared to contemporaries who weren’t exposed to the Good Behavior Game. And she continued to collaborate with researchers at the Bloomberg School, delving into different aspects of suicide.

Defining Depression

At the same time, across the street at the School of Medicine, a young psychiatrist named Karen Swartz began developing ADAP after the deaths of three Baltimore teens by suicide. The program dovetailed with Wilcox’s work. Soon, a shared commitment to young people’s mental health would bring the two women together as research collaborators.

“The curriculum of ADAP in a nutshell is that depression is a treatable medical illness,” says Karen Swartz, MD, Myra S. Meyer Associate Professor in Mood Disorders.

With the help of psychiatric nurses Barbara Schweizer, Sallie Mink and Sally Hess, Swartz gradually molded ADAP into a form much like the one that’s taught today in three hours spread over two or three classes. It includes interactive elements, such as having students think about questions a psychiatrist should ask about depression or putting together a depression public service announcement.

Eventually, Swartz trained teachers and other staff from schools to teach the program, allowing it to spread far beyond its Baltimore-area origins—to Chicago, Austin and Cincinnati, for example. Today, more than 108,000 students have been through the curriculum.

Marcie Gibbons, a social worker at Archbishop Spalding High School, a private Catholic high school in Severn, Maryland, has been teaching the program for five years. At the heart of ADAP, she says, is teaching students to distinguish between “little d” depression (the feelings of sadness that all people experience from time to time) and “big D” depression (the mental illness known as clinical depression).

“There’s two definitions for the same word,” she says. “We’re giving students the language to make that distinction and help them understand that clinical depression is an illness like high blood pressure or diabetes and that it can be treated.”

ADAP is working, adds Kim Carson, a parent whose son and daughter have been through the program at Spalding. Carson says it’s been a relief to know that her daughter, who is graduating this year, will be prepared with knowledge that can help keep her safe when she heads to college in the fall. She says that ADAP is still making a difference for her son, who graduated in 2016.

After a classmate died by suicide just before Christmas in 2018, he drew on lessons from the program to try to understand and process the news. The first person he called wasn’t a friend or parent, Carson says—it was Gibbons.

“By the time he got to us, he had already been through several steps of dealing with the situation,” she says. “Just the fact that he wanted to talk with the person who’d taught him the program and she could be his support system even three years out of high school was fascinating to me.”

Measures of Success

After hearing dozens of stories like this one, Swartz and her ADAP colleagues had good anecdotal evidence that the program was working. But randomized trials are the gold standard in academic research—the standard that others use to assess the value of a program, Swartz says. So, in 2011, she teamed up with Wilcox.

Together, they and their colleagues crafted a randomized effectiveness trial to test whether ADAP was accomplishing their goals of increasing depression “literacy” among students, reducing the stigma of depression and getting help for students who need it. The researchers paired up 33 schools that would receive ADAP that academic year with 33 others that were waitlisted for a year.

Funded by a four-year grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, the team started their work in 2012. Before and after the ADAP program, students and teachers from all 66 schools filled out surveys to gauge their knowledge about depression and their level of stigma toward the disease.

After Wilcox, Swartz and their colleagues crunched the numbers, they found significantly higher levels of depression literacy in the 3,681 students who had undergone ADAP, compared to the 2,998 students who had not, and students retained this knowledge for at least four months after completing the program. Levels of stigma didn’t change between the two groups after the program, but they were already relatively low to begin with. (This could be attributed to limitations with the brief stigma measure or a sign that mental illness is becoming less stigmatized in younger generations throughout the country, Wilcox notes.)

The study also found that nearly half of teachers had been approached after ADAP by students concerned about themselves or others. Of those students requesting depression treatment for themselves, nearly half received it within four months of ADAP’s completion.

Although these numbers don’t directly indicate how many lives this program could save, Wilcox says, it’s well known that having ready access to high-quality mental health treatment can help prevent suicides. ADAP is achieving this, she adds, by helping both students and teachers know when to get help and how to find appropriate mental health resources.

“High school is really a big window of opportunity to educate students … about depression and how to recognize it, when to know when you or someone else needs help, and when to take action,” Wilcox says. “In just this one study, we showed that ADAP is accomplishing all of that.”

The study, published in December 2017 in the American Journal of Public Health, was just the beginning. She and her colleagues have published three additional papers from the research, focusing on subsets of the data including teachers’ depression literacy and how differences in school climate or student gender might affect depression literacy and stigma.

High school is really a big window of opportunity to educate students when they're young about depression and how to recognize it, when to know when you or someone else needs help, and when to take action .... We showed that ADAP is accomplishing all of that.

A Wider Net

Although Wilcox’s research has shown that interventions like the Good Behavior Game and ADAP can make a lasting difference toward reducing suicides in youth, these efforts aren’t enough, she says—even more efforts need to target younger ages. And although most health curricula in the U.S. include a unit on mental health, she adds, those teaching the content often don’t have the training or resources they need to deliver high-quality, research-based content.

That’s why she’s working to bring a program started in Europe, known as Youth Aware of Mental Health, here to the U.S.

Much like ADAP, this intervention aims to teach middle school students about mental health issues, such as depression, using role-play to get these messages across. She and her colleagues are adapting this program to make it culturally appropriate for U.S. students, particularly those in Baltimore City schools’ majority African-American populations.

She’s also examining the utility of a program called Teen Mental Health First Aid, which was developed and tested in Australia. Currently being piloted in eight high schools scattered across the U.S., this program teaches students how to help a friend in crisis. Wilcox says she hopes that this research, funded by Lady Gaga’s Born This Way Foundation, could eventually be expanded to determine whether the intervention could be helpful for students in middle school and younger.

Outside the classroom, she and her colleagues are also trying to reduce suicide risk in children. They recently tested a suicide risk screening tool in Johns Hopkins’ pediatric emergency department on patients as young as 8 years old, showing that it identified twice as many children at future risk of suicide-associated outcomes compared to those identified in clinical care alone.

Together, Wilcox says, each of these efforts, which are easily embedded into school and hospital settings, should help address youth suicide by helping teens, preteens and younger children get the help they need before it’s too late.

“This is something I’d love to see happen in the U.S. It sounds like a really huge goal, but I think it’s attainable,” Wilcox says. “We should have high-quality mental health programming in all schools.”