Covid-19: How to Use History to Make Sense of a Pandemic

No two pandemics are alike, but history teaches us that some behaviors persist.

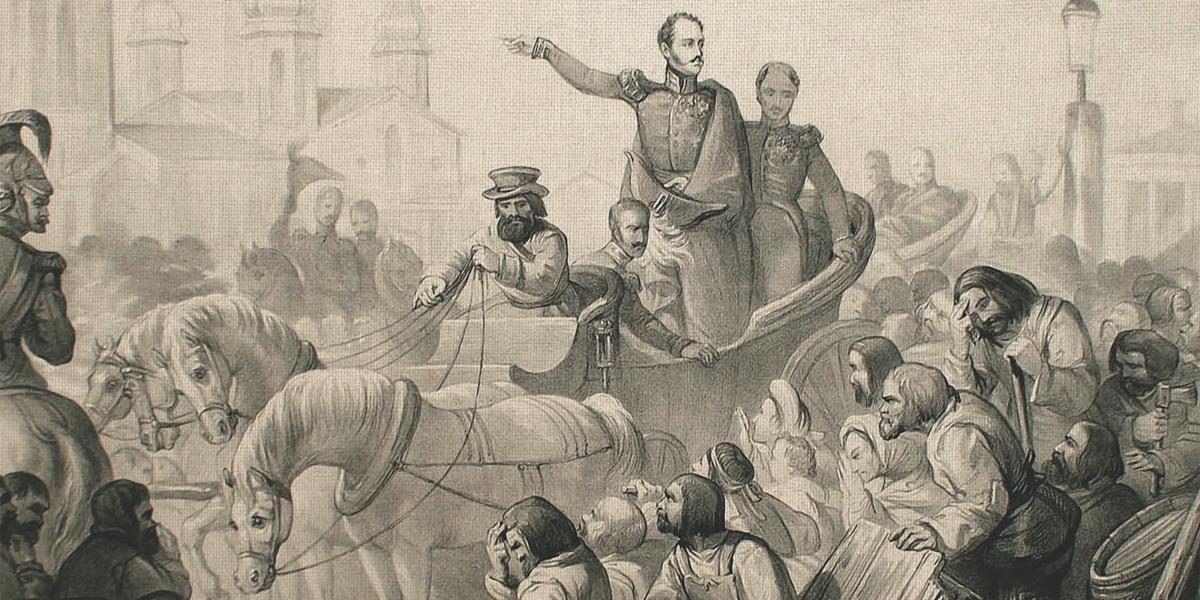

As cholera spread across Europe in the 1830s,“cholera riots” erupted against the preventive measures taken by authorities. The working class saw wealthier people quarantined comfortably at home, while the poor were carted off to hospitals, sometimes never to return. (They also knew the medical establishment’s reputation for “body snatching” of corpses for anatomical study.)

The lesson, says Graham Mooney, PhD, an associate professor of the History of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, is that public health authorities must understand the origins of people’s reactions.

“It may seem irrational, that people went around saying, ‘Well, this is just rich people poisoning the water, so that they can control us,” says Mooney. “Is something rational? Is it nonsensical? It always has a social, political, and cultural context that you need to be aware of.”

Throughout history, people’s reactions to disease interventions have ranged from speedy acceptance to violent denial. But a significant trend recurs, notes Jeremy Greene, MD, PhD, MA, director of Johns Hopkins’ Institute of the History of Medicine. One is a general skepticism of novel medical interventions orchestrated by the government. This skepticism is especially acute in the U.S., which is defined by respect for individualism and civil rights—and suspicion of state intervention.

“There’s a long history of public health intervention being seen as the most intrusive and intolerable extension of the state into people’s personal lives,” Greene says.

While transparency and consistent, accurate messaging have always been critical, today’s public health officials also face an unprecedented informational environment. Our “unique media universe” is essential to understanding the skepticism, hesitancy, and outright denial around COVID, says Greene. “It’s not an accident that the same term, ‘viral,’ is used to describe both the spread an epidemic agent and the spread of news and information through social media,” he says.

Mooney advocates for putting real resources behind public health measures, citing British government efforts in the 19th century to eradicate common diseases such as smallpox and scarlet fever. If the authorities, while attempting to disinfect a home, destroyed a book, say, or window curtains, they replaced them. The understanding was that sacrifice in the name of public health should not just be borne by the individual.

Ultimately, “the key to using history effectively in the public health framework is understanding both the continuity and change,” Greene says. “Past events don’t provide a playbook for the present or the future. History doesn’t repeat itself.”