SCIBAR: Supporting Scientists Who Dream Big

From cool roofs to hidden hunger, a new School initiative confronts big problems with bold solutions.

Go big or go home.

That’s the spirit behind the Bloomberg School’s SCIBAR (Support for Creative Integrated Basic and Applied Research) initiative, which recently awarded $1 million each to four research teams seeking bold solutions to big problems.

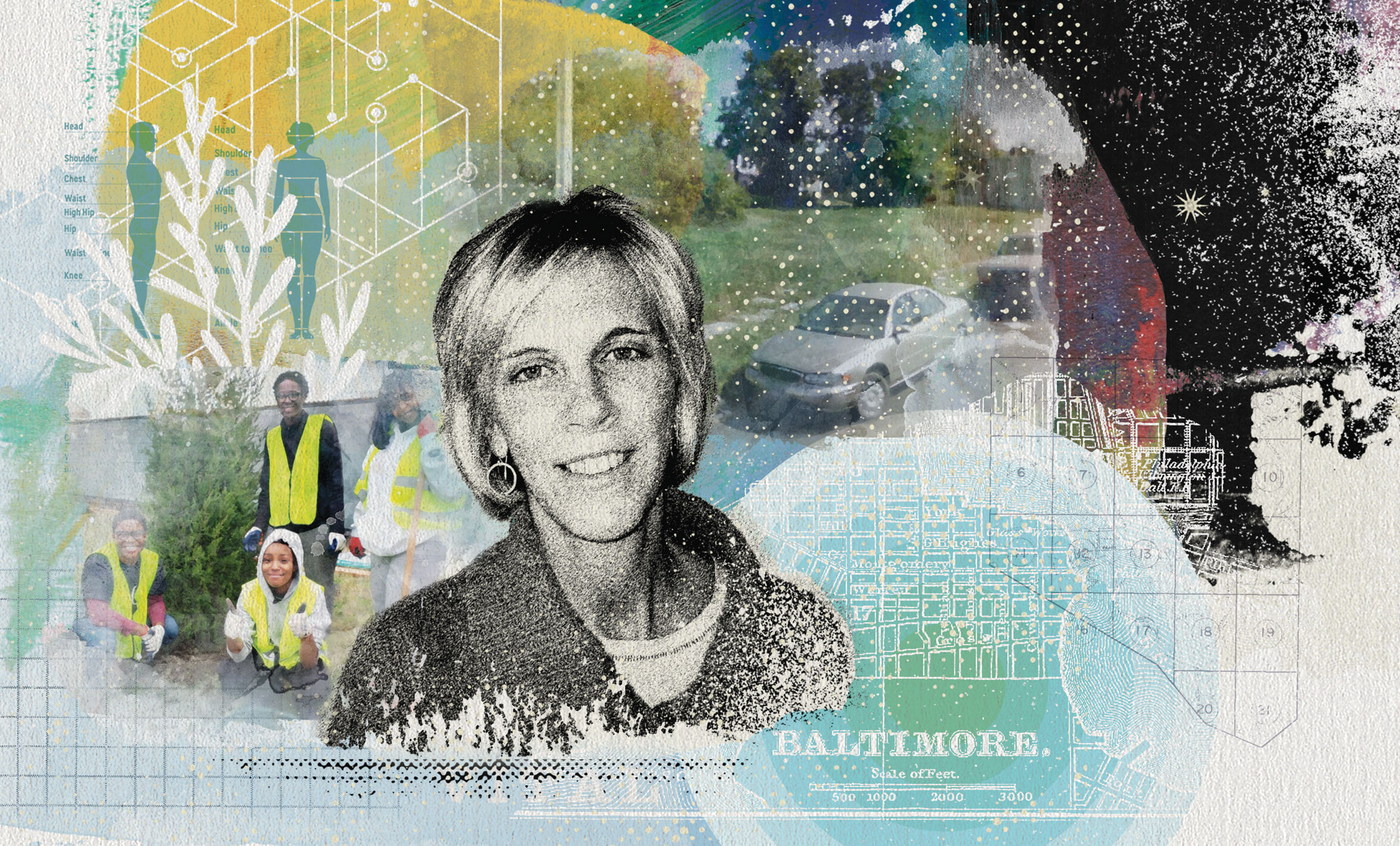

The 44 teams that joined the Schoolwide competition had to meet the same ambitious standard: “It had to be something important for long-term public health objectives on a national or global level,” says Dean Ellen J. MacKenzie, PhD ’79, ScM ’75.

MacKenzie conceived of SCIBAR as a way of leveraging the School’s unique combination of basic and applied research—and its connections within the University and a wide range of community partners. Each project addresses issues of health equity while emphasizing community engagement.

The result: a suite of diverse research projects that aim to make a real difference in the lives of people who suffer from significant health disparities.

“Funding like this allows people to dream big again about public health ideas that can change the world,” says SCIBAR director Nina M. Martin, PhD ’17.

Can restoring vacant lots improve adolescent health?

What’s known

Restoring vacant lots reduces violence and mental health problems among adults who live nearby, with the greatest benefits accruing to disadvantaged populations.

What’s needed

Proof that the same phenomenon applies to adolescents—and a playbook for cities to follow if it does.

The goal

Kristin Mmari, DrPH, MA, hopes to create a blueprint that municipal leaders can use to reduce adolescent health disparities: a portfolio of greening strategies, complete with benefits and price tags, that can transform vacant lots into drivers of adolescent health.

“That’s our dream,” she says.

“We’re going to cost out all of these greening efforts and look at what you get.”

What’s next

Mmari, an associate professor in Population, Family and Reproductive Health, wants a Green New Deal for adolescent health.

Mmari has spent the last few years studying the impact of neighborhood factors on adolescent well-being. Now she wants to see if greening vacant lots—installing flower beds, building community gardens—improves mental health outcomes and food security for adolescents while reducing their exposure to violence.

The Baltimore Green Network Plan, an existing city initiative to transform vacant properties into community assets such as parks and urban gardens, provides an ideal way to find out.

“This is a really unique opportunity,” says Mmari, who calls her initiative Project VITAL (Vacant Lot Improvement to Transform Adolescent Lives). “It’s kind of like a natural experiment.”

Mmari has enlisted the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance, which collects neighborhood-level data on quality-of-life measures such as teen birth rates and healthy food availability, to build a database of every vacant lot and greening program across the city. It will also detail the level of adolescent engagement: Are adolescents from the neighborhood planting gardens and flowerbeds, or is a contractor just mowing the lawn and picking up trash once a week?

Colleagues at the Bloomberg School’s Spatial Science for Public Health Center will map this data so the team can select a group of lots for a study involving 700–1,000 adolescents ages 15 to 19. Some will live near sites that involve high levels of community engagement; others will live near sites that do not. This will allow the researchers to see if participating in the greening process makes a difference. The team will also analyze the costs and benefits of the different approaches being used.

“We’re going to cost out all of these greening efforts and look at what you get,” Mmari says.

Can cool roofs improve health equity while combating climate change?

What’s known

So-called cool roofs that have been coated with materials that reflect sunlight lower indoor temperatures, reducing air conditioning needs and saving energy and money.

What’s needed

Evidence that they also can mitigate the disproportionate impact of rising temperatures on the health of disadvantaged populations.

The goal

Kirsten Koehler, PhD, MS, and Adam Spira, PhD, MA, aim to provide cities with a roadmap to mitigating the urban heat island and related health disparities in one fell swoop—just by modifying the roofs we sleep under.

“This might be a way to directly and indirectly improve all sorts of health consequences.”

What’s next

Koehler and Spira want to see if a simple engineering solution can improve sleep and other health outcomes while combating climate change—all by making use of Baltimore’s ongoing efforts to install cool roofs on homes.

Koehler, an associate professor in Environmental Health and Engineering, explains that cities are urban heat islands where asphalt and other dark surfaces absorb sunlight more readily than in surrounding rural or greener suburban areas. That leads to higher temperatures, a phenomenon exacerbated by traditional tar-and-gravel roofs that turn bedrooms into pizza ovens in summer.

In addition to heat exhaustion and heatstroke, extreme temperatures contribute to everything from asthma to disrupted sleep—which itself can drive negative mental and physical health outcomes.

Those least able to afford air conditioning suffer the most. But installing cool roofs that reflect rather than absorb sunlight could drive down temperatures inside homes and maybe even across entire neighborhoods, mitigating climate change by reducing energy use for air conditioning and ameliorating health problems.

“This might be a way to directly and indirectly improve all sorts of health consequences,” says Spira, a professor in Mental Health who researches sleep and aging.

To ensure that they are investigating the health outcomes that matter most to the community, the team is consulting with Baltimore residents, including those who are already slated to have cool roofs installed.

The team will measure indoor temperatures and air quality before and after cool roof installation. They will also measure sleep and monitor a variety of mental and physical health outcomes pre- and post-installation. Colleagues in other departments like Pulmonary Medicine at the School of Medicine will help to better understand the potential health impacts.

A health economist will put numbers on the benefits of the cool roof installations. And Earth & Planetary Sciences faculty at the Krieger School will use spatial modeling to determine if cities can reap the benefits of cool roofs without having to install one on every house.

Can Fresh Research Shed Light on Opioid Use Among Native Americans and Improve Policies?

What’s known

Native Americans experience higher rates of death due to opioid overdose than any other racial or ethnic group in the U.S.

What’s needed

A better understanding of injection drug use in tribal communities and the factors that drive it—along with an evidence-based toolkit for combating the problem.

The goal

The team aims to produce a multimedia toolkit that will help tribal groups around the country share their stories, conduct research on sensitive topics, and influence policy change.

“We want all of the data to be locally relevant and actionable,” says Sean Allen, DrPH, MPH. “And that only happens through community involvement and partnership.”

“This is really going to be community-led, and the outcomes will be what the communities want.”

What’s next

Allen and Melissa Walls, PhD, MA, are making community engagement the centerpiece of their effort in two American Indian communities: the Bois Forte Band of Ojibwe in Minnesota and the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Members of both tribes will serve as co-investigators, and community research councils will help conduct the study.

“This is really going to be community-led, and the outcomes will be what the communities want,” says Walls, an associate professor in International Health and director of the Great Lakes Hub for the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health. (She is also a first-generation descendant of Bois Forte and Couchiching First Nation Anishinaabe.)

The opioid epidemic has hit indigenous communities especially hard. But researchers still don’t know how many Native Americans use injection drugs at the community level or precisely how local factors influence drug use.

That’s partly because population estimation methodologies have mostly been applied in urban areas, and fear and stigma lead to underreporting. For example, Native people who use drugs can have their children taken from them and placed in foster care—part of a long, traumatic history of such removals.

“We know people are overdosing. And the reason it’s going unreported is out of fear,” says co-investigator Pamela Hughes, a Bois Forte Band member who is the substance use disorders program director for Bois Forte Tribal Government.

As a result, tribal councils and policymakers lack the information they need to address the problem.

Team members will adapt population estimation methods to estimate the proportion of people who inject drugs in two tribal communities. And they will explore how engagement with traditional practices such as powwows and sweat lodges can exert a protective effect.

Can a new way of measuring micronutrient deficiencies end hidden hunger?

What’s known

Mild but chronic deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals (a.k.a. hidden hunger) can cause everything from stunted growth to impaired immunity, affecting billions of people. Most of the harm accrues to women and children in resource-poor countries.

What’s needed

A cheap, quick, reliable, and valid way to identify micronutrient deficiencies so populations can be adequately assessed and get the food or supplements they need.

The goal

In four years, Keith West, DrPH ’86, MPH ’79, aims to have a prototype device that could be used to reveal population-level micronutrient deficiencies. He plans to use that prototype to drive further support for using biomarkers as a tool for preventing hidden hunger and promoting better health where the need to do so is greatest.

“SCIBAR is like manna from heaven, giving us the resources that we’ve been waiting for,” he says.

“SCIBAR is like manna from heaven, giving us the resources that we’ve been waiting for.”

What’s next

West aims to harness new technologies to reduce dependency on difficult and expensive lab techniques by measuring proxy biomarkers of blood micronutrient levels.

State-of-art methods aren’t much help in rapidly identifying deficiencies across large groups of people in impoverished settings—or in rapidly targeting interventions like fortifying foods and distributing supplements to ward off the ravages of hidden hunger.

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t prevent it,” says West, a professor in International Health.

Rather than measuring micronutrient concentrations directly, West and his colleagues predict micronutrient levels across large groups of people based on the amounts of proteins related to nutrients in their blood plasma—something that could in theory be done quickly and inexpensively.

So far, they have been able to predict levels of a handful of essential micronutrients such as vitamins A and E with sufficient accuracy to estimate deficiencies. Scaling the method up will require two things: conducting basic research to find more proteins that can predict more nutrients, and packaging the protein-testing technology in a portable, user-friendly device.

West has assembled experts from the Bloomberg School, the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and Bangladesh to carry out additional research and sophisticated modeling needed to accurately predict micronutrient levels from protein concentrations. And he is partnering with a private biotech firm that has developed a cutting-edge platform for measuring proteins in the blood.

The team plans to apply its new approach by measuring nutrients and proteins in plasma samples drawn from hundreds of pregnant women in rural Bangladesh—an at-risk group amongst whom micronutrient deficiencies can result in low birth weight, premature birth, and pregnancy loss.